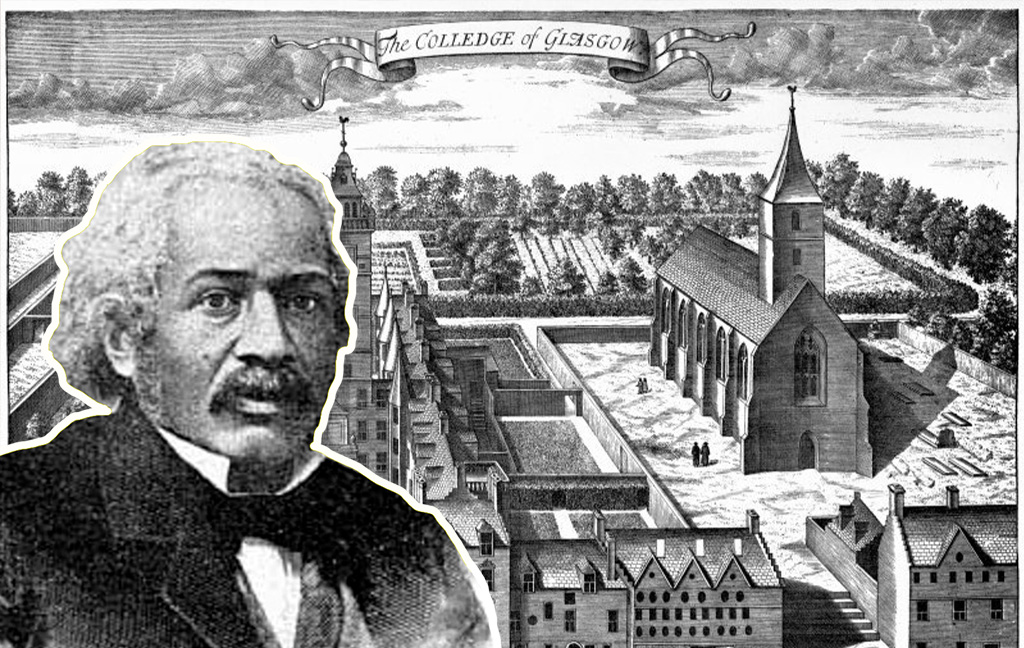

In 1832, a young Black man by the name of James McCune Smith enrolled as a medical student at the University of Glasgow. His graduation five years later was a landmark moment. McCune Smith became the first African American citizen to gain a medical degree.

McCune Smith had a long career as a respected medical doctor, writer, and civil rights advocate. Despite these achievements, the life and work of McCune Smith was relatively unknown until recently. In 2021 – almost 200 years after his graduation – the University of Glasgow named the newly opened James McCune Smith Learning Hub in his honour.

In this blog we will follow Doctor James McCune Smith on his Scottish journey with images from our archives.

Leaving the Land of the Free

McCune Smith was born to an enslaved mother in 1813. In 1799, New York state had passed a Gradual Emancipation Act. This meant that children born after July 4 1799 were indentured into their young adulthood. In 1827, McCune Smith and all of New York’s remaining enslaved people were liberated by the state’s Emancipation Act.

The young James was a promising student and attended the African Free School. When he graduated, he applied to a variety of colleges in the United States. However, despite being an exemplary student, his applications were all rejected due to his race. Ultimately, he ended up attending university across the Atlantic in Glasgow.

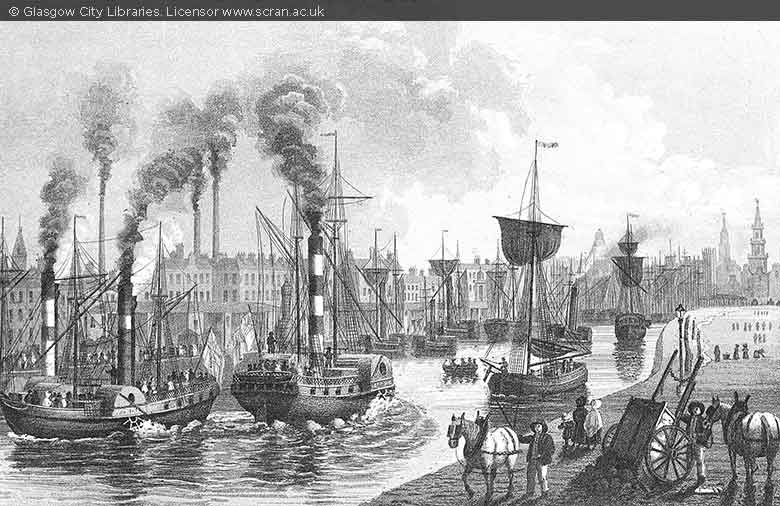

In 1832, McCune Smith travelled from New York to Liverpool aboard the ship ‘Caledonia’. After that, he travelled to Glasgow via steamer, probably disembarking at the Broomielaw.

This illustration from 1834 shows Broomielaw as busy commercial port. See it up close on Scran.

An historic place of learning

During the 1830s, the University of Glasgow was situated on the High Street, it moved to its current location in Glasgow’s west end in the 1870s. This was not the first time the university had moved, when it was originally founded in 1451, the university lectures took place in Glasgow Cathedral.

At Glasgow, McCune Smith studied subjects such as Greek, Anatomy, and Medicine. He may have won prizes for his academic achievements. McCune Smith would have been familiar with the buildings in this nineteenth century photograph. The foreground building is the old university library, and the row of buildings in the background is the Hamilton Building, which contained a dissecting room.

William Adam Library, Old College, Glasgow. This image dates to around 1880 and you can zoom in for more detail on Canmore.

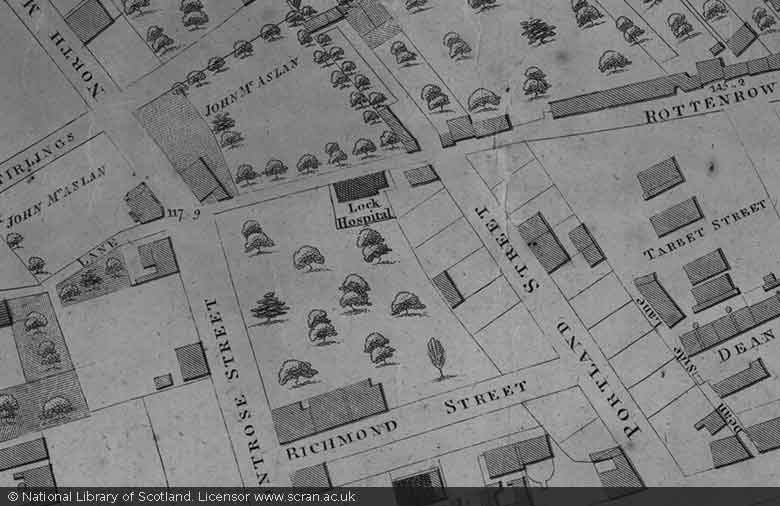

Lock Hospital

After his graduation in 1837, McCune Smith was granted a trainee position as Clerk at the Glasgow Lock Hospital. The Lock Hospital was a hospital for women with sexually transmitted infections. It had been established in 1805 and in an 1826 publication it was described as:

‘a plain edifice, so completely enclosed, that the inmates cannot see beyond the courtyards’.

It was while working at this dingy institution in Glasgow’s Rottenrow, that McCune Smith campaigned for the welfare of the patients. In 1837, he published articles in the London Medical Gazette which exposed the mistreatment of patients at the hospital by a fellow medical practitioner. The articles showed McCune Smith’s desire to use his medical training to help people less fortunate than himself. These articles are also the first known research papers to be published in a British medical journal by an African American.

The site that the Lock Hospital occupied was later used for the Glasgow Royal Maternity Hospital. When this was demolished, the site became a park.

Take a look at this full 1807 map of Glasgow over on Scran.

Ardent abolitionist

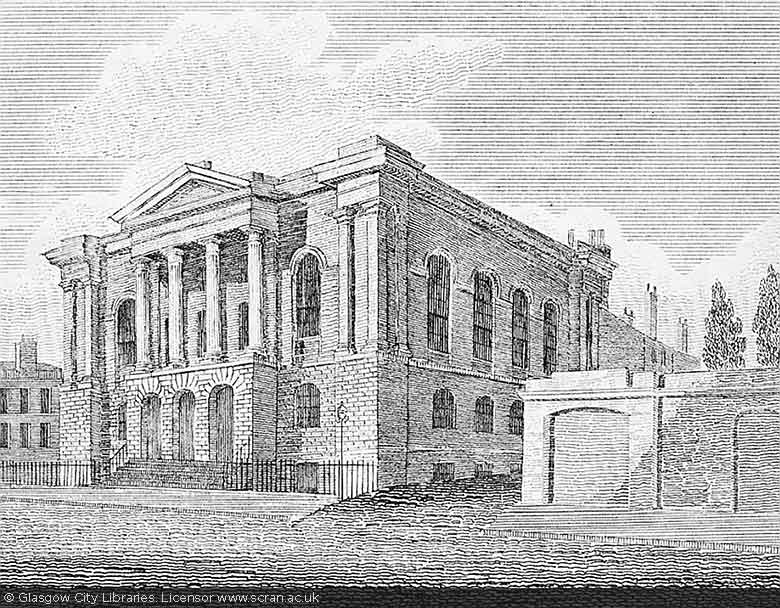

During his time in Glasgow, James McCune Smith was a founding member of the Glasgow Emancipation Society. At a meeting of the society in March 1837, held at the George Street Chapel, McCune Smith was cheered when he said:

at a day not very distant, it may be my privilege once more to appear before you,—no longer an outcast from the land of the free—no longer the victim of a cruel prejudice—no longer debarred from seats of learning”.

In June 1837, McCune Smith was made an Honorary Member of the Committee of the Glasgow Emancipation Society. His fellow society-members wrote that:

…We felt ourselves called upon to esteem you for your virtues, and to admire you for your intellectual powers and attainments…”

George Street Chapel was built in 1819. It was one of several churches in Glasgow to host meetings of anti-slavery societies. Find out more about George Street Chapel on Scran.

That Autumn, McCune Smith left Glasgow. After spending some time working in Paris, he returned to New York.

In the United States he continued to practise medicine. He also opened a pharmacy which was open to all, regardless of their race.

In 1855, he penned the introduction to ‘My Bondage and My Freedom’, the second autobiography of fellow abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Douglass had also spent time living, working and campaigning in Scotland.

In the introduction to Douglass’s memoirs, McCune Smith wrote stirringly about ‘the indestructible equality of man to man’. This was a principle which remained close to Doctor McCune Smith’s heart until his death in 1865.

And finally…

Read more about Scotland’s Black heritage in our Black History archive. Meet Britain’s first Black teacher and the ‘Moorish lassies’ who served the Scottish royal court.

Learn more about the history of education in Scotland. Search for schools, colleges and universities in our archives on Canmore and Scran.

Feature image credits: Dr James McCune Smith from ‘Recollections of Seventy Years’ by Daniel Alexander Payne (1811-1893), published in 1888. ‘The Colledge of Glasgow’ from Theatrum Scotiae by John Slezer.