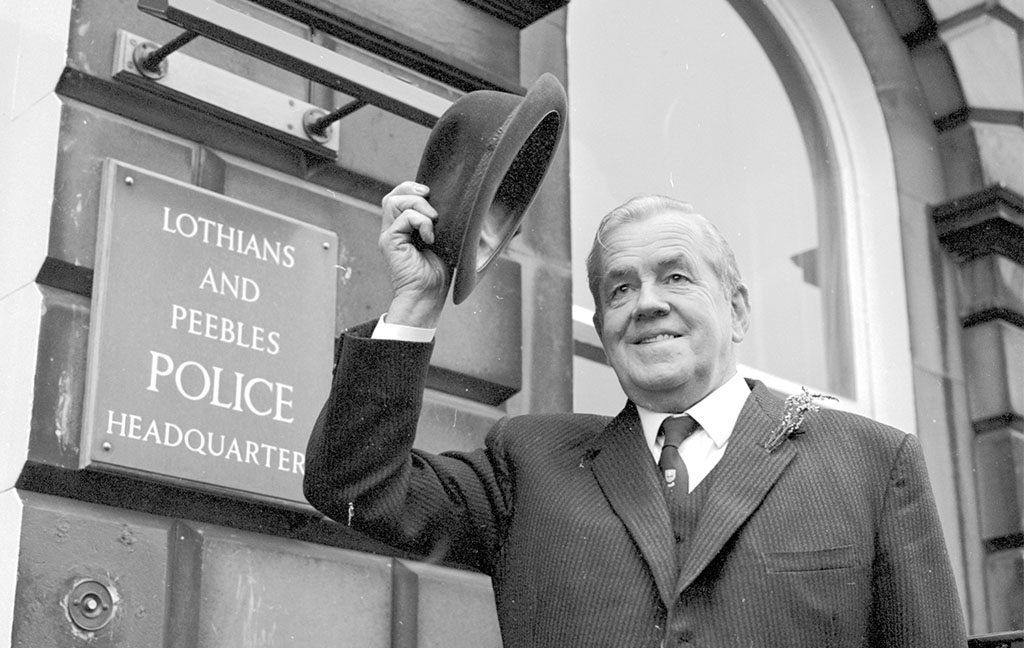

William Merrilees figures prominently in the history of Edinburgh policing. Under regulation height by four inches and missing the fingers from his left hand – the result of an industrial accident – he didn’t meet the criteria to join the police force. However, Merrilees’ heroism – rescuing over 20 men and boys from Leith Docks – saw him recommended for service. He joined in 1924, at the age of 26.

His rise through the ranks was rapid. By 1940 he’d been promoted to the rank of detective superintendent, in charge of CID. Between 1950 and his retirement in 1968 he was the Chief constable of Lothian and Peebles. Such a remarkable career progression was the result of his strong commitment to law and order and his involvement in a number of high-profile criminal cases.

As you might expect from a blog on the persecution of queer people, there is some discussion of violence and harassment. There is also some material relating to sexual activity that may not be suitable for younger audiences.

Targeting gay men

During the mid 1930s much of his time was occupied by a series of cases concerning male homosexuality. Merrilees had initially been alerted to a ‘worrying’ increase in the number of men prosecuted for so-called homosexual offences in Edinburgh by the then procurator-fiscal James Adair.

Adair is a prominent and notorious figure in the history of homosexual law reform in post-war Britain. He was a member of the Wolfenden Committee in the 1950s, and a firm opponent of the decriminalisation of sex between consenting males in private. Adair’s concern saw Merrilees tasked with leading ‘a special enquiry into sodomy in Edinburgh’. Merrilees later described this enquiry as a ‘war on homosexuality’.

Stalking the streets

If we are to believe the accounts that Merrilees offers of this period detailed in his autobiography, this seems to have been an investigation he undertook almost singlehandedly. However, Merrilees frequently embellished his recollections.

What he might not have embellished were his claims that he occasionally meted out his own form of justice. He stalked the public urinals, parks and public baths of the city, collecting names and addresses. He later claimed he would be able to ‘point out at least 50 sodomites in Princes Street and the vicinity’ on any given evening. Some of them might also be able to identify him, especially if they were amongst the men beaten or harassed by the detective. Merrilees was an intimidating figure with ‘a fist like a stone mallet’. His approach to questioning suspects and witnesses was equally problematic.

The Rosebery Boys

One of his investigations focussed on the Rosebery Boys, a small group of queer male sex workers operating out of the outwardly respectable Rosebery Hotel in Haymarket.

Edinburgh’s Haymarket area in the early 20th century. Image © Courtesy of HES (Francis M Chrystal Collection).

His investigation led him to Lochgelly. There he interviewed one vulnerable 17-year-old witness at length, without any other officers present. This young man was a close friend of one of the Rosebery Boys, James Allan.

Allan had written to Lochgelly to detail his love for ‘Jack’, a sailor he had recently met. The last time that James Allan saw ‘Jack’ was when ‘Jack’ was brought by Merrilees to Saughton Prison to identify his former lover.

Either through the threat of prosecution or other forms of coercion, the Lochgelly youth also provided evidence against his good friend. Allan was convicted of sodomy and sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment. The deeply personal letters he had sent to his friend in Lochgelly formed part of the evidence against him.

Pursuing Peter Ogg

Merrilees was satisfied by his role in the Rosebery Boys case but had now gained an appetite for rooting out homosexuals. The next target for Merrilees was the Edinburgh businessman Peter Ogg. Ogg was the proprietor of several business across the city, including Maximes Dancehall.

The site of Maximes Dancehall is still a nightclub in Edinburgh.

During his ‘enquiries’ the name of Ogg and his friend Ewan King had cropped up regularly. This led to Merrilees to assume that these men organised most of the homosexual life in the city. For the authorities, homosexuality was considered a ‘trade’, akin to sex work. They thought it was organised by powerful members of Edinburgh society who provided bodies and opportunities for illicit pleasure.

Ogg was suspected of being a prime player in such a trade. Merrilees had a theory that Ogg was supplying soldiers from Redford Barracks to queer men from Edinburgh, Fife and Northern England.

Redford Barracks, where soldiers involved in the case were stationed.

These investigations took him to Morpeth, Northumberland, where he detained three men.

Entrapment and false confessions

In the course of this investigation, Merrilees took pride in his ability to affect the supposed mannerisms of a homosexual. Adopting a walk and lisp, he apparently convinced one of the men that he was a friend of Ogg’s visiting for the purposes of sexual adventure.

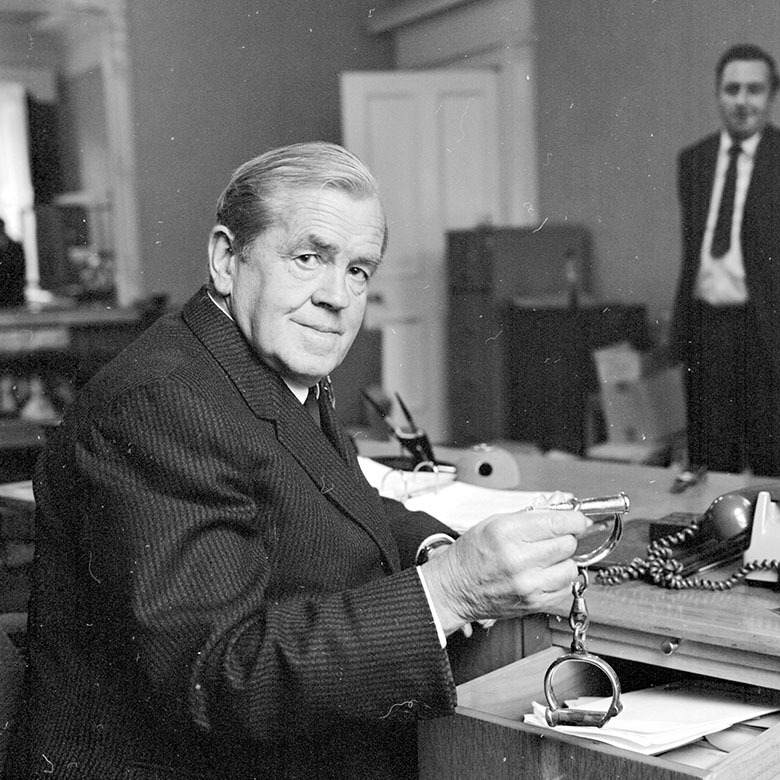

William Merrilees dedicated a chapter in his memoirs to discussing his “war on homosexuality” and the cruel techniques he employed.

Once each of the men had been ensnared in his trap, Merrilees undertook lengthy, confrontational and intimidating interrogations. Despite one of the men insisting another officer remain present, Merrilees conducted these interviews alone.

When the interviews had ended the witnesses were shown their statements. The statements had been recorded in Pitman’s Shorthand, which meant the interviewees could not read the notes. Subsequently, most of the Morpeth witnesses disputed the contents of their statements at trial. They highlighted intimidation and the invention of details of which they had no knowledge.

The investigation reached its key point when King’s hotel was raided. The police found the hotelier in the company of a soldier. Ogg had by this point travelled home.

Eight hours after the raid on King’s hotel, Ogg had been arrested and a search was undertaken by Merriless of the businessman’s office within Maximes. Evidence including a ‘damp’ hankerchief was seized. The handkerchief was a key piece of evidence that supposedly linked Ogg to the events at King’s hotel. Yet during the trial Merrilees’ conduct was questioned with the suggestion that the handkerchief seized during the search was not the same handkerchief used in evidence. The inconsistencies with this evidence were highlighted by the trial judge in his summing up. Nevertheless, Ogg was found guilty of an offence with a soldier and for two other offences. He was found either not guilty or not proven for the remaining four offences. He received a sentence of two year’s imprisonment, which he partly successfully appealed.

Tall tales from a short detective

When writing his autobiography Merrilees significantly embellished his version of the case. He placed himself centrally and invented quite ludicrous escapades which according to the trial records, and his own evidence, did not happen.

What the evidence suggests is that Ogg may have occasionally met men for sex. These were sometimes soldiers, sometimes civilians. He may well have introduced some of his soldier friends to his friends from Morpeth. They might have gone out for dinner or to the theatre.

Soldiers from Redford were regular visitors to Maximes. However, claims of mass orgies involving soldiers and notable Edinburgh businessmen are fanciful. Yet Merrilees seems to have gone to extraordinary lengths to secure convictions.

William Merrilees spent considerable time undertaking charity work for disadvantaged children and ex-prisoners. He featured on This is Your Life and received an OBE. However, his sense of charity did not extend to the queer men he played such a central role in sending to prison.

About the Author

Jeff Meek is a lecturer in Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow. His book, Queer Trades, Sex and Society: Male Prostitution and the War on Homosexuality in Interwar Scotland, will be published by Routledge in the Spring.

Explore more

Find more blogs on Scotland’s LGBT+ history.

Banner image of William Merrilees © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.