As Local Hero celebrates its 40th anniversary, Jonathan Melville traces the film’s origins, from the typewriter of writer-director Bill Forsyth to the silver screen.

Starting out

Bill Forsyth at the Scottish Referendum vote-count, 1997 (© Colin McPherson. Licensed by Scran)

It was while he was fresh out of school in his native Glasgow that the teenage William “Bill” David Forsyth found himself working as an assistant to a local documentary filmmaker on a salary of £3 a week. Within a month he was writing scripts for short sponsored films while also helping to shoot and edit them.

After moving on to International Film Associates (IFA) Scotland, Forsyth worked on films for the Films of Scotland collection, a series charting the changing face of Britain.

A still from 1966’s The Smiths in Scotland, one of the many Films in Scotland shorts Bill Forsyth worked on as a production assistant. (© National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive. Licensed by Scran)

By the late 1970s, Forsyth had made the decision to move away from documentary filmmaking. He began toying with ideas for a feature-length screenplay, working closely with young actors at the Glasgow Youth Theatre.

When this script failed to receive funding, Forsyth and the young actors developed a story based around the problems faced by Glasgow youths trying to find work in a deprived city.

Councillor Pat Lally and Rev. Alastair Moodie of St. Paul’s Church of Scotland, on a tour of deprived areas in Glasgow in 1975, pass kids playing on top of the remains of a mini-van. (© Newsquest, Herald & Times. Licensed by Scran)

Raising his tiny budget from local businesses and working with crew such as production manager Paddy Higson and a young cast, Forsyth’s first feature as writer-director was 1978’s That Sinking Feeling.

A Meeting of Minds

During a visit to London with That Sinking Feeling Forsyth was introduced to film producer David Puttnam. He’d had success with 1977’s The Duellists and 1978’s Midnight Express. Keen to raise money to make his second feature, Forsyth handed Puttnam his ‘Gregory’s Girl’ script. He hoped the producer might take an interest.

Though Puttnam turned down the opportunity, busy as he was trying to put his own film Chariots of Fire into production, he did help secure distribution for That Sinking Feeling and introduced Forsyth to his new agent.

Undeterred, Bill Forsyth returned to Scotland and secured the funding to make Gregory’s Girl in the New Town of Cumbernauld in 1980. Gregory’s Girl starred John Gordon Sinclair, Dee Hepburn and Clare Grogan in a story of young love and football.

Claire Grogan outside Glasgow Film Theatre (© Alan Wylie. Licensed by Scran)

Planning Local Hero

Bill Forsyth and David Puttnam’s paths crossed once more in September 1980. This time it was by accident, in a Soho tobacconist’s shop.

While Forsyth was editing Gregory’s Girl nearby, Puttnam was completing work on Chariots of Fire.

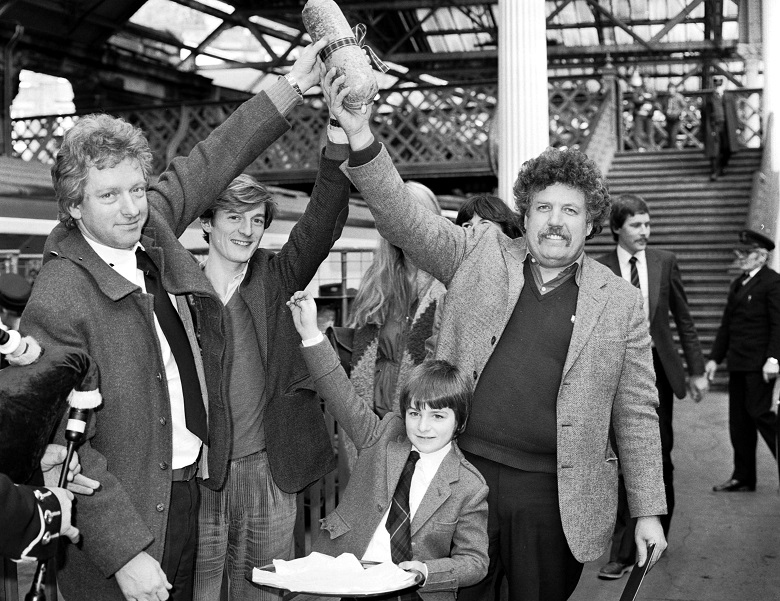

‘Chariots of Fire’ team – director Hugh Hudson (left), actor Nigel Havers and writer Colin Welland (right) – at Waverley Station (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed by Scran)

A few days later, Puttnam invited Forsyth to a screening room to watch Ealing Studios’ 1949 film, Whisky Galore!, tipping Forsyth off that Puttnam was thinking that the pair should collaborate on a film set in Scotland.

Puttnam had been doing some research into Scotland’s oil industry, specifically Shetland’s oil boom which had hit the headlines in 1972 when Shell-Esso announced that oil had been found in the Brent oilfield, 100 miles northeast of Shetland’s capital, Lerwick. It was then announced that a new £20 million oil terminal handling 300,000 barrels a day was to be built at Sullom Voe.

Sullom Voe oil terminal (© Shetland Museum & Archives. Licensed by Scran)

Boomtown

What stood out to Puttnam was the stance taken by Shetlanders to the arrival of the oil, specifically the Council’s fight to ensure that the huge sums of money that would soon flow into the coffers of the oil companies would also help Shetlanders.

Thanks in part to county clerk Ian R. Clark in long negotiations with Westminster, special funds were established that were exempt from certain taxes. The idea was to ensure that new schools, houses, leisure centres and more could be built, along with improvements to the island’s public health and social work departments.

Seeing potential in a David vs Goliath story about the ordinary man fighting the establishment trying to make money out of their land, David Puttnam convinced Bill Forsyth to outline his ideas for a potential new screenplay.

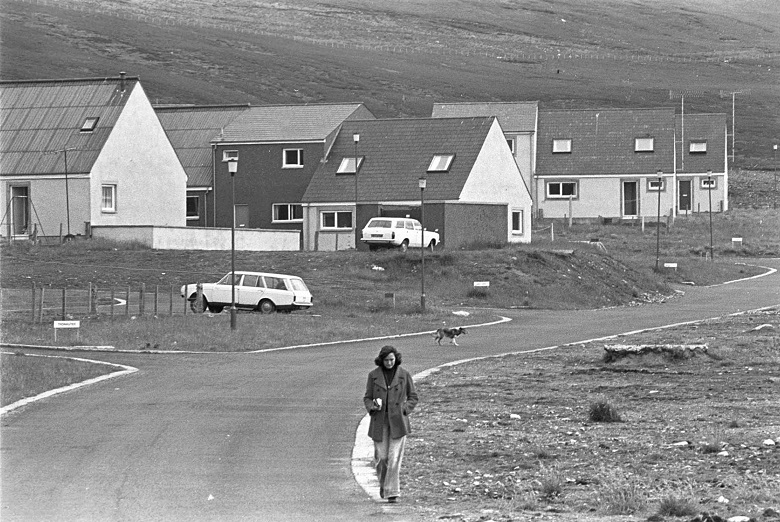

The village of Brae, the scene of a huge housebuilding program in the 1970s. (© Tom Kidd. Licensed by Scran)

The Rocks and the Water

Keen to avoid focusing too much on the board room negotiations and the industrial side of the oil industry, Forsyth decided early on that his film would be “A Scottish Beverly Hillbillies”, a reference to the 1960s US comedy revolving around a poor American family who strike oil and move to Beverly Hills with their new found riches.

He also felt some kinship with the 1945 Powell and Pressburger film I Know Where I’m Going starring Helensburgh-born actress Deborah Kerr and partly filmed near the Gulf Of Corryvreckan in the Inner Hebrides.

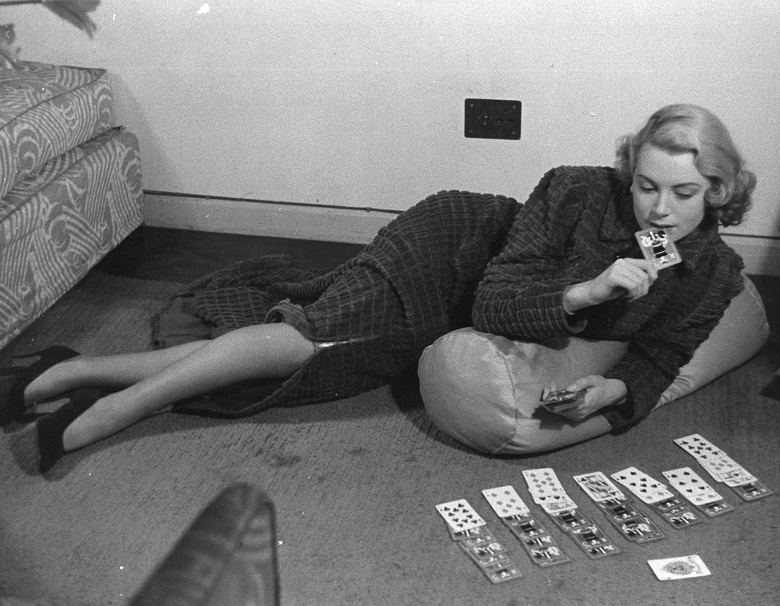

Actress Deborah Kerr playing patience. (© Hulton Getty. Licensed by Scran)

The story of Local Hero slowly evolved through numerous versions of his screenplay. It originally focuses on a local hotel owner who takes on the mighty oil companies before settling upon a young Houston oil executive, “Mac” MacIntyre (Peter Riegert). Mac is sent to Scotland by his boss, Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster), to buy the land required to build a new oil refinery.

On arrival he meets the Aberdeen-based Danny Oldsen (Peter Capaldi) and the pair travel to the Highland village of Ferness. There they meet solicitor Gordon Urquhart (Denis Lawson) and locals who are keen to get their hands on American cash.

With the script written, all that was left was to find a real-life Ferness to shoot the exterior scenes.

Finding Ferness

The task of locating a real Scottish village with a beach that could double as Ferness was handed to Local Hero’s production designer Roger Murray-Leach who drove around the coast of Scotland searching for the perfect location. He soon realised that nothing quite matched what Forsyth needed. Nevertheless, he did find the small fishing village of Pennan in Aberdeenshire, close to the larger town of Banff.

Pennan Village, Aberdeenshire (© James Gardiner. Licensed by Scran)

With its single street overlooking the sea and picturesque harbour, Pennan would make the perfect Ferness, though Bill Forsyth was still unhappy that the beach that wasn’t close by.

Sadly the phone box made famous by the film was only a prop brought to Scotland by the crew, but today a real (category C listed!) phone box sits a few metres away sheltered from the wind.

In the end it was decided that Ferness would be a composite of two locations, with Aberdeenshire standing in for the village while Camusdarach Beach, situated between Arisaig and Morar on the west coast of Scotland, would stand in for “Ben’s beach”.

The road between Morar and Arisaig (© St Andrews University Library. Licensed by Scran)

Cast and crew

As important as it was to find the perfect Ferness, it was equally vital to find the right cast. Forsyth and casting director Susie Figgis were keen to find a mixture of new and familiar faces for Local Hero.

For MacIntyre’s boss, Happer, Forsyth chose Hollywood legend Burt Lancaster, who embraced the opportunity to play the eccentric billionaire.

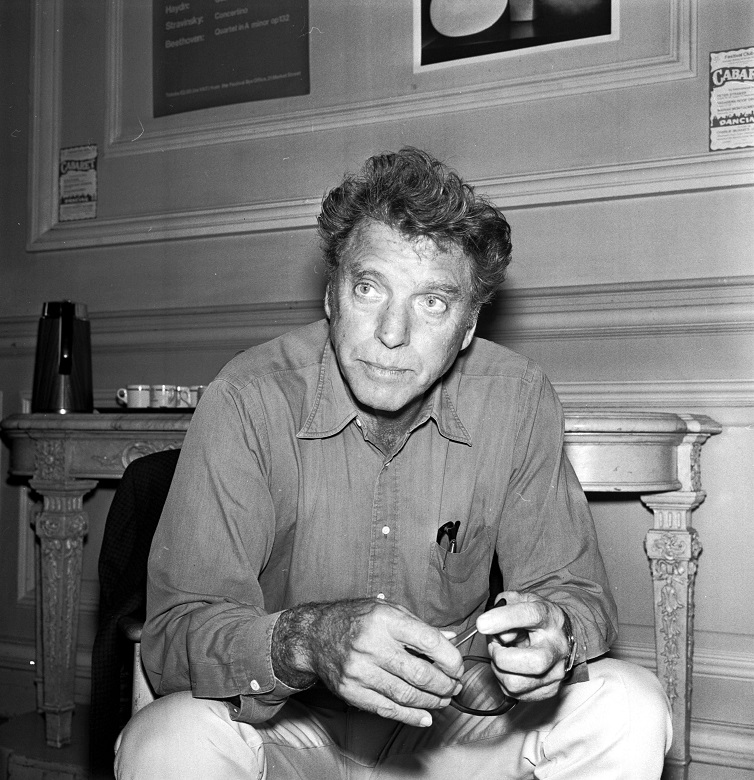

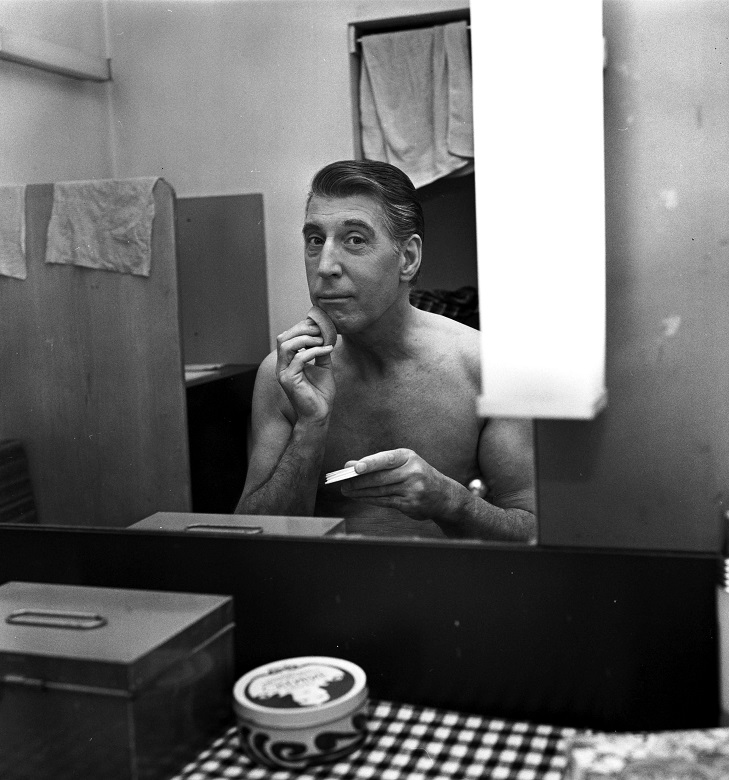

Burt Lancaster in Edinburgh in 1976 (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed by Scran)

New York-born actor Peter Riegert was chosen to play MacIntyre. The part of his second in command, Oldsen, went to young stand-up comedian, musician and graphic designer, Peter Capaldi. It was his first acting role.

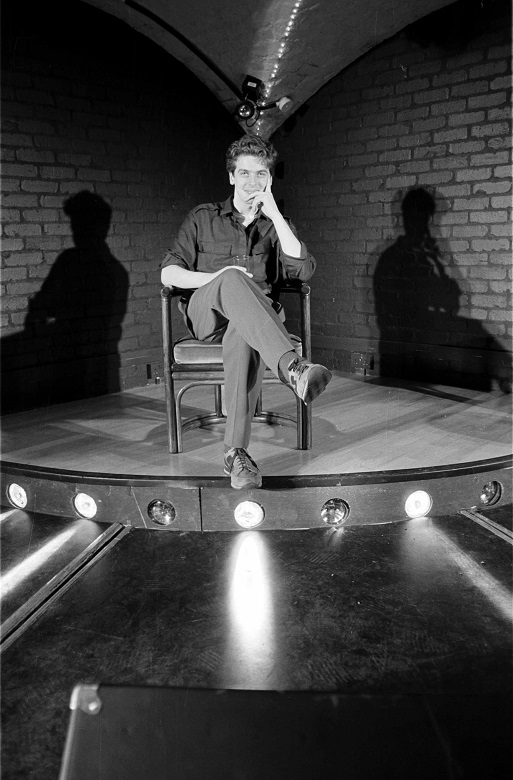

Peter Capaldi (© Alan Wylie. Licensed by Scran)

The role of Ben Knox, whose ownership of the beach causes problems for MacIntyre’s deal, was given to Fulton Mackay. He was known to TV audiences at the time for playing Mr Mackay in Porridge.

Roddy McMillan (left) and Fulton Mackay (right) (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed by Scran)

Scottish actor and comedian Rikki Fulton took on the smaller role of Dr Geddes, a replacement for actor Bill Paterson.

Rikki Fulton backstage at the King’s Theatre in Edinburgh in 1981 (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed by Scran)

A number of other well known faces populated the cast including Jimmy Yuill, Dave Anderson, Jennifer Black, Jenny Seagrove and Alex Norton.

A grand opening

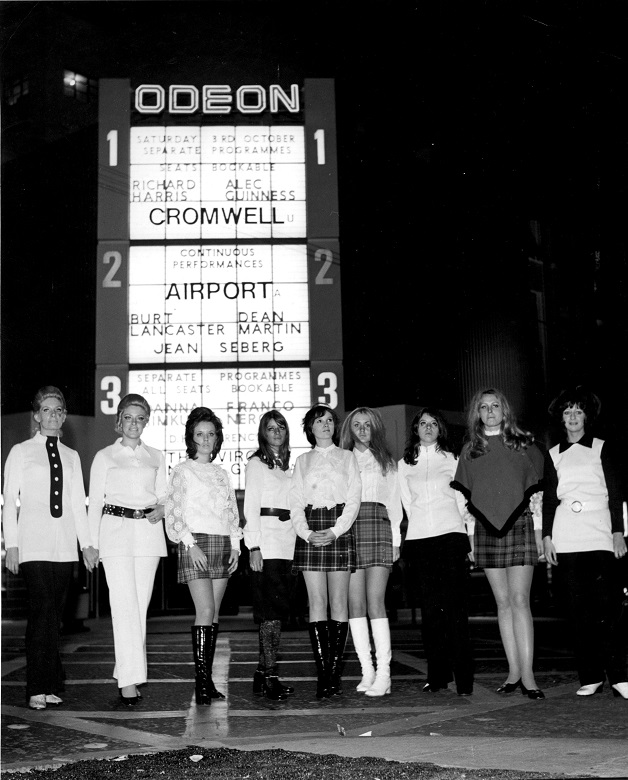

Completing filming in the summer of 1982, Local Hero’s Scottish premiere took place at the Odeon cinema on Glasgow’s Renfield Street on 16 March 1983. Many of the cast and crew were in attendance including Peter Riegert, Peter Capaldi and Fulton Mackay.

Bill Forsyth told Evening Times journalist Alasdair Marshall that he was keen to keep making films in Scotland:

“We’ve been moaning about making films in Scotland for years. I’d be daft not to do it now that I’ve got the chance.”

Opening in UK cinemas on 29 April 1983, Local Hero received generally positive reviews. The Guardian’s Derek Malcolm wrote “If he made no other films other than That Sinking Feeling, Gregory’s Girl and Local Hero, Bill Forsyth’s place would be secure as the most original comic director to emerge within the British cinema.”

The Odeon is reopened in 1970 (© Newsquest, Herald & Times. Licensed by Scran)

In fact Forsyth did go on to make more films in Scotland, including 1984’s Comfort and Joy starring Bill Paterson and Claire Grogan, 1994’s Being Human with Robin Williams and 1999’s Gregory’s Two Girls with John Gordon Sinclair, along with a handful of films in America.

Forty years on from its release, Local Hero remains an undisputed Scottish classic. Fans from around the world still visit Pennan to try and find the phone box Mac used to call Houston.

As for the film itself, it still holds a few mysteries – including:

- whether Marina is actually a mermaid

- whether that’s really Mac calling Ferness in the final scene

- if he ever did get on a plane and fly back to Scotland.

Perhaps it’s best we never know.

Jonathan Melville is the author of Local Hero: Making a Scottish Classic, available now from Polaris Publishing.