Scotland’s relationship with its Gypsy Traveller population is a complex one. From romanticised to demonised, it can feel like Scotland is determined to “other” this culture, despite its long history as part of Scotland’s story.

In this blog, Shamus McPhee, an artist, activist and Nacken, takes a look at nearly 500 years of oppression. Please be aware that this blog uses some terminology which some may find offensive.

Renaissance Scotland

Persecution has regularly visited upon Nackens, or Gypsy Travellers, in Scotland. Time and time again, we see it throughout the annals of history. Since the mid-sixteenth century successive purges have been aimed at eradicating the culture.

While records show that Gypsies were initially welcomed into Scotland, the Reformation signalled a downturn in group fortunes. The first anti-Gypsy law was enacted in 1541. Gypsies were to leave Scotland “under the pain of death”.

The year 1571 saw the Act of Stringency heighten the punishment for anyone convicted of being a Gypsy. This became the order of the day for the ensuing 33 years. Hanging, branding, drowning, pinning Gypsies to trees by the ears, lopping off ears and deportation were all legalised.

In 1603, the Privy Council ordered all Gypsies to leave Scotland, never to return, again, on pain of death. The “Act Anent the Egiptians” was ratified in 1609. Many examples of executions carried out under this Act are recounted by Sir Walter Scott in a series of articles in the Edinburgh Magazine of 1817 and by David MacRitchie in his work, Scottish Gypsies under the Stewarts. Scott’s listings include evidence of a total of nineteen hangings in the first month of 1624. It was also under this law that Jamie MacPherson was hanged, along with James Gordon, on 17 November 1700.

From Scotland to Scandinavia

Given the level of reprisal, it is known that some Scottish Nackens, or Gypsy Travellers migrated to Scandinavia. It is perhaps not insignificant that the term Näcken, pronounced ‘Necken’, appears in Scandinavian folklore as the name of an unsavoury water sprite.

Certainly, we know that Finnish, Swedish and Norwegian Romani attribute their origins to migrant Scottish Gypsies. These groups were in turn expelled from Sweden in 1637. this is part of a pattern of purges on Gypsy Travellers that can be found all over Europe. In many of these cases, Gypsies were ordered to leave and could be executed when they failed to comply.

Death and deportation

The last individuals to be executed in Scotland for being Gypsies were Agnes McDonald and Jean Baillie. The two women were sent to their deaths in the Grassmarket, Edinburgh, in 1714.

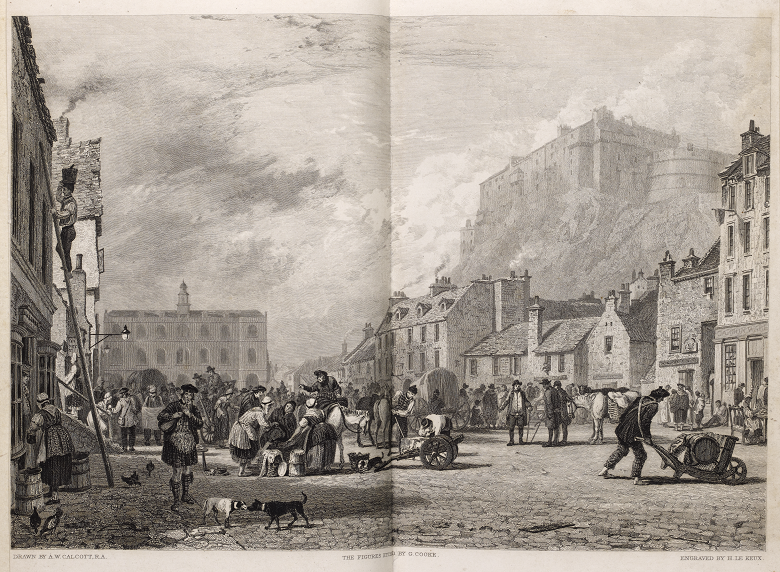

The Grassmarket as it appeared in the 1820s, 100 years after Agnes McDonald and Jean Baillie were executed. The last hanging in the Grassmarket took place in 1784. Zoom in on this image on Canmore.

Death was not the only punishment meted out at this time, however. In 1701, Alexander Stewart, believed to be a Gypsy Traveller, had his death sentence for theft commuted to being a ‘perpetual servant’ in Scotland. A brass collar inscribed with his name and crime, as well as his sentence, is in the National Museums Scotland.

The collar worn by Alexander Stewart. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Gypsy Travellers were also shipped to plantations in British colonies. As early as 1665 there are records of Gypsies in Scotland being deported to plantations in Jamaica and Barbados. Among other examples, around 1714, eight Gypsy Travellers were ‘sentenced to be transported to the Queen’s American plantations for life’.

Culture change

While the eighteenth century was overshadowed by deportations and executions, by the nineteenth century, the authorities switched their focus to a clampdown on nomadism.

The Trespass (Scotland) Act, 1865, made it an offence to encamp or light a fire on a road or cultivated ground, in or near any plantation, without the prior consent of the landowner. It also empowered police forces to arrest, detain and present before a magistrate any perpetrator. Section 3 of the Trespass Act is still most commonly invoked to pursue an eviction to this day.

‘No Common Ground’ © Shamus McPhee.

A roadmap to extinction

Following this, in 1894, Sir George Otto Trevelyan, Secretary for Scotland, commissioned an Inquiry into Habitual Offenders, Vagrants, Beggars, Inebriates, and Juvenile Delinquents. It served as a catalyst in the drive to “extirpate” Gypsy Travellers – the aim was to eradicate the culture completely. It was hoped that they would be “absorbed into the labouring population”.

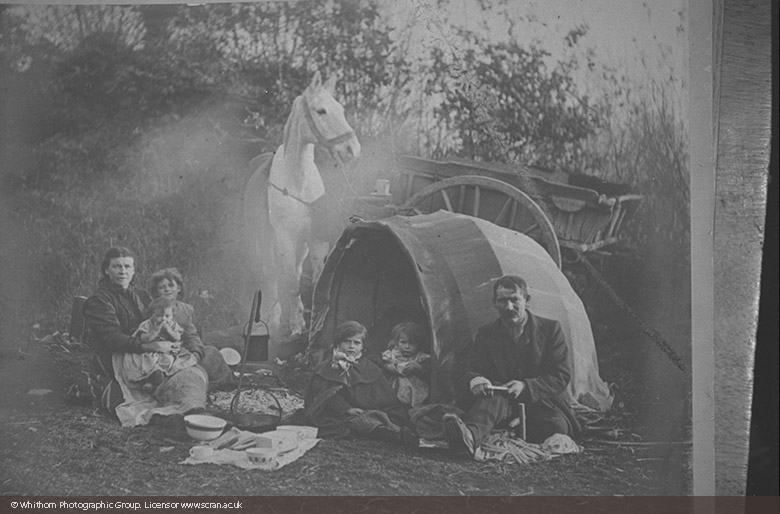

This photo, taken around 1906 shows a Gypsy family camped in Galloway.

The 1895 Scottish Traveller Report drew up a number of recommendations that would govern policy thereafter. It advocated the creation of ‘reserves’ to contain Gypsy Travellers and that education to be used as a tool to disable the culture. Children were to be taken from their parents and placed in industrial schools or under the care of charities such as Quarriers and Barnardos, or on Mars ships (for correctional training). Others were to be shipped abroad to the colonies, primarily to Canada and Australia.

On a mission

During WWI, the Departmental Committee on Tinkers in Scotland sprang up. Initially this national body was tasked with the rehabilitation of servicemen and their families. It wished to “anchor the tinker” and make him prove useful to society. Soon the government, local authorities and churches were working in partnership. Their goal was to expunge the scourge that they perceived to be a blight on society. Increasingly, churches became involved in home missionary work, striving to reclaim the sinners and banish “the increasing evil”.

Semi-permanent compounds, such as that established by The Free Church in Campbeltown, were being trialled during the winter months. Parents were encouraged to stay long enough for children to be educated out of their nomadic ways. The plan was to “lengthen the time of control gradually” and ultimately to settle these families.

Dorothea Maitland, one of the Church of Scotland’s home missionaries undertook a study visit to Surrey in 1932. There she toured a camp for Gypsies run by the control committee. This led to conversations between the Department of Health for Scotland and the Departmental Committee on Tinkers in Scotland as to whether experiments of this sort could be used in Scotland. The intent here was to find a model to forcibly settle and assimilate the Gypsy Traveller population in Scotland.

Newspaper reports from the 1910s to the 1940s refer to planned experiments to settle and assimilate Gypsy Travellers across Scotland. Councils in Angus, Caithness, Moray and Perthshire all developed plans.

Housing experiments

My research into one such experiment established at Bobbin Mill in Pitlochry has revealed details of these types of plans. I have a personal interest in the site, as I was born there.

In 1946 a de-commissioned military prefabricated building was relocated to the site of an old mill for use as accommodation. The Department of Health took on the responsibility of running and maintenance costs on the agreement that these were kept to a minimum. The accommodation was to be deliberately sub-standard. It was feared that anything superior might “prejudice the success of the experiment”. The residents were to be “subject to fairly close supervision”, and monitored over a twenty-year period.

Within a decade of the initiation of the Bobbin Mill experiment, Mr J. Nixon Browne, Joint Under Secretary of State for Scotland, was able to disclose in a Westminster debate, that Gypsy Traveller numbers had been cut dramatically across Scotland, from 4,260 families to 345.

Still with us today

Police powers to prevent camping, coupled with housing experiments meant that Gypsy Travellers began to disappear from habitual roadside camps. Pressure applied to camping through the Trespass Act was further strengthened by the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, 1994. It bestowed additional powers on police attending an encampment to decide if an offence had been committed. It became unlawful to stop, even with the landowner’s permission.

Although the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, allows for camping, it includes strict limitations on time and numbers camping. Under this Act, there is still no chance for Gypsy Travellers to meet and camp as extended families at traditional stopping places.

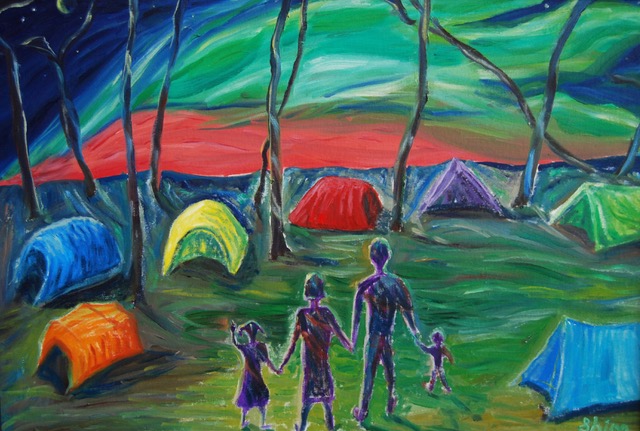

‘Wild Campers Catch the Lights’ © Shamus McPhee.

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month

The persecution faced by Gypsy Travellers has changed over time. Expulsion, execution, transportation and laws against camping have all played their part. Gypsy Travellers continue to be recognised as one of the most marginalised and discriminated against groups in Scotland today. Ongoing discrimination led to the establishment of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History Month (GRTHM) in 2008.

Looking to anti-colonial and anti-racist models of working, GRTHM highlights the history Gypsy, Roma and Travellers (GRT) in the UK. It both celebrates GRT culture and heritage, as well as making visible the more difficult parts of their history. For information on events in Scotland celebrating GRTHM 2023, as well as an archive of films and resources from previous GRTHMs in Scotland, please visit www.GRTHM.scot.

About the author

This blog was written by Shamus McPhee. Shamus is a Nacken, artist and social justice activist. Dr Rhona Ramsay provided some academic input. She is a researcher who recently completed a thesis on the absence and presence of Gypsy/Travellers in Scottish museums.

Banner image: Big Chill at Bobbin Mill by Shamus McPhee.