Did you know that during the 1400s and 1500s, when Linlithgow Palace was in use, Scots was the language of the Scottish kingdom? It was spoken by the monarch and ordinary people alike. It was also the written language of the state and record.

The Scots language that is still used by hundreds of thousands of people across Scotland today is the modern version of that historical Scots. But where Medieval Scots was the language of court and Parliament, the status of Modern Scots is quite different.

The central role of Scots as the spoken and written language of so much of Scotland’s history is often forgotten. Many Modern Scots speakers aren’t even aware that they speak a different language.

The new audio guide in Scots at Linlithgow Palace is the first of its kind.

Celebrating Scots both past and present

Although Scots is still spoken widely, you don’t often hear it in official or formal settings. That’s why I was so excited to be invited to work on the Linlithgow Palace audio guide. Not only does it celebrate the historical importance of Scots, it also recognises (and showcases!) it as a modern and dynamic language that’s still very much in use today.

There are two new tours on offer at the palace: one in Scots and one in English. Whether you choose to experience the English or the Scots version, you’ll hear content both in and about Scots.

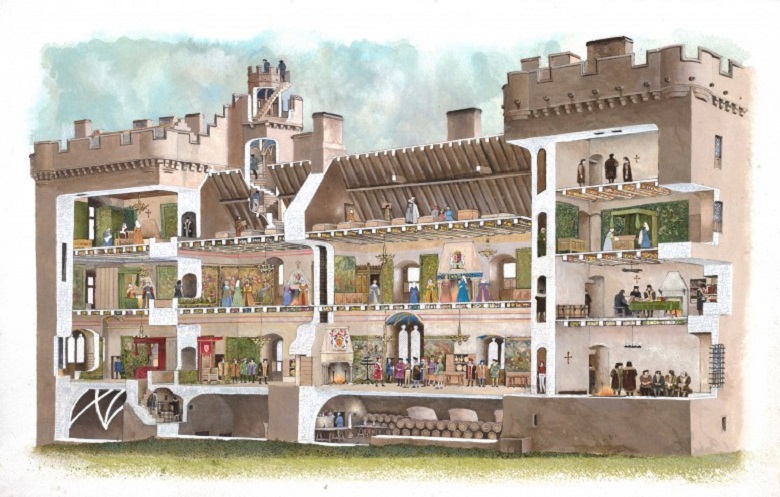

When Linlithgow Palace was in use as a royal residence, Scots was the language of the court. Reconstruction image of the royal palace in 1512 by David Simon.

Two languages, two tours

The different needs of our Scots and English-speaking audiences led to different approaches to the level of Scots content in each tour.

Both tours include the voice of a narrator, who’s your trusted guide around the palace. As you explore its different areas, you’ll also meet a range of characters, who’ll tell you what it was like to live and work around the palace.

On the Scots tour, both the narration and the character voices are in Modern Scots.

On the English tour, the narration is in Scottish English, while the character voices are in a Hybrid Scots-English.

Developing the Scots tour

The script for the tour was developed by Historic Environment Scotland in English. I then translated this script into Everyday Modern Scots. There are variations in how Scots speakers use and understand Scots. These can depend on the speaker’s age, where in Scotland they’re from (their dialect area) and how often they speak, hear and read it (their fluency). I wanted to make the tour as accessible to as many modern speakers as possible.

Listen to this clip from Stop 1. Keep an ear out for Scots words!

How many did you spot? Verbs like daunder and ken, adjectives like muckle, nouns like Lithgae, adverbs like the noo and the day, prepositions like fae and tae and phrases like dinnae fash are all Scots.

You might also have noticed Scots features like the singular ‘year’ in twa hunner year, or the ‘-it’ ending on the verb in includit.

Tae big or not tae big

As often happens when a language becomes minoritised, Scots has long been excluded from educational and formal settings. This means that many Scots speakers don’t have reading and writing skills in the language they speak. They also often don’t know much about its history or literature.

In this context, the Scots script uses every opportunity to showcase the richness and distinctiveness of Scots, but without ever risking the alienation of the everyday speaker.

Putting accessibility first sometimes meant using a word shared with English, even where a distinctly Scots alternative exists, if I felt that the Scots could be too challenging for an everyday speaker.

For example, tae big (to build) and biggin (a building) are great Scots words, derived from Old Norse, but they’re not in widespread usage today. Using them could have put off a Scots listener, who might not recognise those words. I took the same approach when opting for kingdom over kinrick, reveal over kythe and if over gin.

In some cases, I introduced less common Scots words in context. In Stop 14, I have the narrator describe how “the palace had tint, or lost, muckle o its lustre”. Tint comes from the historical verb tae tyne (to lose). It’s present in Scots sayings like tak tent or it’s tint (use it or lose it). The gloss – or explanation – makes sure that all visitors understand the meaning of the more advanced Scots, and could give people some new (old!) words for their vocabulary!

Not just translation – but word creation

Minoritised languages like Scots often don’t develop new vocabulary organically, especially in specialist areas like technology. As a translator, you can either use the word of the dominant language (in our case, English) or you can create a new Scots term. To ensure accessibility, as always, the meaning of any new term must be immediately clear to an everyday speaker, who’ll never have encountered it before.

For example, using lug-in to mean audio is a brand new coinage I made for this project. Tae lug-in (from lug, meaning ear) means, as a verb, ‘to listen’ or ‘tune into’. Here, I used lug-in as an adjective to refer to the audio guide.

Our voice artists – and the diversity of Modern Scots

The most exciting part of the process was recording with our narrators and voice artists. They really brought each tour to life! We recorded with bairns and adults, professional actors and everyday speakers, and folk from Banff to Paisley and everywhere in between.

As there’s no standard written Scots, my script took an accessible approach to spelling. I included guidance on pronunciation and was also there to support during recording sessions. But there was loads of space for our artists to bring their own voices and dialects to their characters – which they very much did! The outcome is an audio experience that gives visitors a real sense of the rich diversity of spoken Modern Scots.

Here’s a taster of how Martha (aged 10 at time of recording; now proudly 11) brought young Princess Elizabeth, a daughter of King James VI, to life for the Scots tour.

Developing the English tour

For the English tour, the narrator’s voice was drafted and delivered in Scottish English: that is, English spoken with a Scottish accent and sprinkled with Scots words. Listen out for rolled rs and the “ch” sound in Scots words like loch.

Scottish English isn’t a separate language from English. But it is the unique form of English that’s spoken and written in Scotland.

Listen to the same clip from Stop 1 of the English tour.

As well as the Scottish accent, you’ll have noticed how the first sentence was in Scots, then repeated in English. You’ll also have heard Scots words used clearly in context (daunder) or with a gloss (lugs/ears).

The character voices: hybrid Scots-English

The shared roots of Scots and English (each developed from different dialects of Anglo-Saxon) mean that there are strong similarities between the two languages, in a way that there simply aren’t, for example, between English and Gaelic.

But these similarities are not unlimited. Scots and English are closely related, but, ultimately, different languages. Scots has many unique words and expressions, as well as its own pronunciation system, sentence structure and grammar.

For many English speakers who aren’t from Scotland, even a Scottish accent can be new and unfamiliar.

For the character voices, the aim was to work with both the similarities between Scots and English and the acting skills of our voice artists to include as much Scots as possible – but without losing our English-speaking visitors. We wanted to turn the dial up towards Scots as far as we could, to give visitors the strongest possible flavour of Scots.

Project Manager, Fiona Fleming (L) and Ashley (R) in the recording studio.

Baby bear’s porridge – just the right amount of Scots

In the development phase, we tried out various versions of the script, containing more or less Scots, on non-Scots speakers. This helped us determine where the tipping point into lack of understanding lay. We took a careful note of what sort of words people didn’t understand, what sort of pronunciations they found confusing, and what sort of speed was too fast.

Using the feedback, we adjusted each character voice to include as much Scots as possible. The final voices are just right: not too hot (too much Scots), but not too cold either (too little Scots).

I also used the gloss technique again: this time, not to introduce Scots speakers to advanced Scots, but English speakers to basic Scots. The voices include glosses like bletherin and chattin and wabbit, exhausted and uncomfortable.

Listen to the same character voice in its hybrid version.

Note how Ah wantit tae greet has changed to Ah wantit tae cry. We discovered that we couldn’t rely on a non-Scots speaker knowing the meaning of tae greet as to cry in Scots. Similarly, Scots telt has become English told. Ah doot it awfie muckle has been dialled right down to Ah doubt it very much.

A lot of words have changed their pronunciation towards English: hame > home, noo > now, whit aboot > what about.

But lots of Scots markers remain: from words like Lithgae and didnae to prounciations like tae and Ah.

All in all, the character voices retain a strong Scots element. This gives English-speaking visitors a real sense of the Scots language used by the everyday people and royal household of Renaissance Scotland – as well as a strong flavour of the Modern Scots language of Scotland today!

Ready tae lug-in at Lithgae?

I hope this blog has made you excited to go and experience one of our new audio guides for yourself. Whether you select the “Scots” or “English” tour when you visit, you’ll learn loads, both in and about Scots.

Hae a braw visit / Have a great visit!

About the author

Ashley Douglas (she/her) is a multilingual researcher, writer, translator and consultant, specialising in the Scots language and LGBT history.

Ashley Douglas (she/her) is a multilingual researcher, writer, translator and consultant, specialising in the Scots language and LGBT history.

You can discover more of Ashley’s work on Scots here:

- Scotland’s linguistic landscape: Scottish Standard English and Scots

- Scotland’s linguistic landscape: Scots and Gaelic

- Minoritised Languages in Translation: Case Study Scots

- Translating Scotland’s Heritage

Elsewhere on our blog, discover the powerful role language has played in Scotland’s history and heritage in this blog by Ruairidh Graham.