We work on a huge variety of interesting sites in the HES Designations Team, but sometimes we get one that is really special. Europe’s first commercial steamship, Comet, is one of those. The pioneering paddle steamer was the creation of the visionary Helensburgh entrepreneur, Henry Bell. It was wrecked off Craignish Point in Argyll and Bute on 15 December 1820.

Earlier this year, we designated the wreck of Comet as a scheduled monument after it was discovered by underwater archaeologists. Nearly 203 years since it went down, it adds a new chapter to the ship’s fascinating story.

The ‘ingenious and enterprising Mr Henry Bell’

A portrait of Henry Bell by James Tannock (© Scottish National Portrait Gallery, licensed via Scran)

This description by the famous engineer, Thomas Telford, captures the essence of Henry James Bell. Born in the village of Torphichen, West Lothian in 1767, Bell’s early working life was as a stone mason, millwright, ship modeller, apprentice engineer and carpenter.

He first began to make the case for investment in steam-powered navigation as early as 1800 when he submitted proposals to the Admiralty. Despite support from figures such as Admiral Nelson, these overtures were largely ignored by the establishment.

Around 1806-7, capitalising on the growing popularity of sea bathing, Henry Bell and his wife Margaret, moved to Helensburgh. They built and operated the town’s saltwater baths and the former Baths Hotel. Bell also served as the first Lord Provost.

During this time, he redoubled his efforts to demonstrate the potential of steamships.

The evolution of steam

‘First Steamboat on the Clyde’ painted by John Knox around 1820. The steamboat, which is in the middle of the river between the sailing vessels, is likely to be the Comet. (© Glasgow Museums, licensed via Scran)

Most ships until the early 19th century were powered by sail. The first successful attempt to build a steamboat was by the Marquis de Jouffroy D’Abbans in France, 1783. His Pyroscaphe successfully sailed on the River Saône, but further progress was hampered by a lack of funds and the French Revolution.

In North America, John Fitch succeeded in producing a viable paddle steamer in 1790. It transported passengers between Philadelphia and Trenton, New Jersey. But the venture failed to attract enough passengers.

James Rumsey worked in both North America and England on his ideas, supported by Benjamin Franklin. However, Rumsey died unexpectedly in 1792 and his designs were never fully realised.

Advances in Scotland and on the Seine

An illustration of the Comet passing Dumbarton Castle while sailing on the Clyde. (© The Mitchell Library, Glasgow City Libraries and Archives, licensed via Scran)

Advances continued into the early 19th century when Lord Dundas, Governor of the Proprietors of the Forth and Clyde Navigation commissioned William Symington to build a steam-propelled towboat for the canal in 1801. Charlotte Dundas was successful but short-lived due to fears that backwash from the boat would damage the canal.

The most influential steamboat pioneer was Robert Fulton, an American who studied canal building in Britain before moving to France. From there, Fulton, in partnership with Robert Livingston, began working on designs for a paddle steamer that would ply the Hudson River between New York and Albany. Initial trials on the River Seine in France in 1802 proved successful and once back in America he launched Clermont in August 1807. This was the world’s first commercial passenger steamer.

PS Comet

A replica of ‘Comet’ which was commissioned to mark the 150th anniversary of its first voyage. It was once located near Port Glasgow town centre, but has since been removed. (© HES. Reproduced courtesy of J R Hume, licensed via Scran)

Henry Bell was not only aware of the developments of steam-powered vessels in America but was in contact with Robert Fulton. Bell’s experiments and trials to build his own paddle steamer began in 1809.

According to the Greenock Telegraph, he used an experimental steam engine to heat his swimming pool, before transferring the technology to the Comet project.

Comet was built in Port Glasgow by John Wood & Sons of Port Glasgow and launched in 1812. It was recorded as 40 feet long, with a 10½ foot beam with small projections on either side to cover the paddles. It had a cargo capacity of 25 tons. The wooden vessel was propelled by a steam engine of 4 horse power built by the engineer John Robertson and boiler by David Napier.

Bell named the vessel Comet after the Great Comet of 1811, a celestial event in which a comet passed by the earth and was visible to the naked eye for 260 days.

Full steam ahead

Helensburgh Pier photographed from the air in 1927 (© HES Aerofilms Collection, zoom in on Canmore)

When Comet entered service on the Clyde from 15 August 1812, she was the only steamship in operation. Passengers were carried between Port Glasgow and Helensburgh. In 1816, Bell improved their journey further by building Category C-listed Helensburgh Pier.

Steam propulsion offered great advantages over sail as vessels could navigate against wind and tide. The benefits of this pioneering approach were soon clear. By 1819, there were 25 steamships on the Clyde, bringing major advances in the transport of passengers and cargo by sea.

Comet, along with its many competitors, continued to ply the main routes on the Clyde for eight years before moving to the Forth. Then, from September 1819, it took on a new Glasgow to Fort William service, passing through the Crinan Canal.

For the more open waters of the west coast, Bell required a larger, more powerful vessel so Comet was lengthened to 73 feet 10 inches and installed with a new 14hp engine. The original engine (which was supposedly sold for re-use in a brewery in Greenock!) is now on display in the London Science Museum.

Wrecked on the Dorus Mor

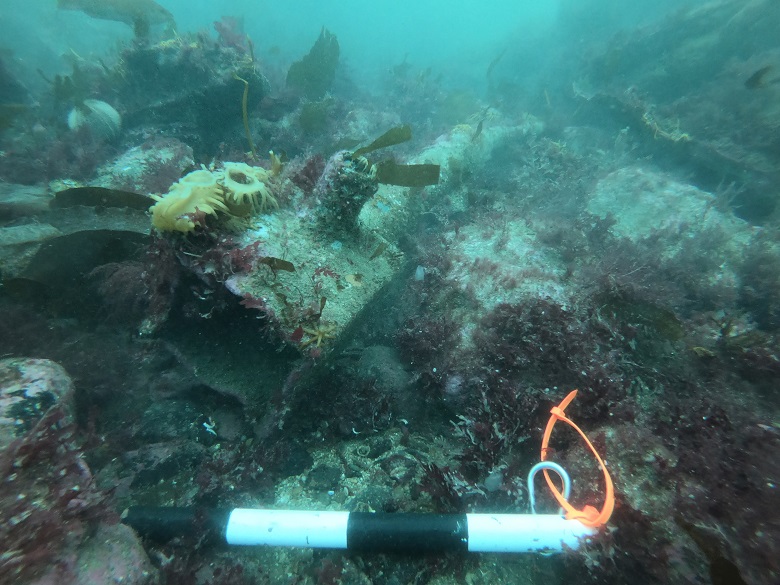

Underwater photos taken by Wessex Archaeologty show the remains of the Comet.

The new west coast route initially proved successful. However, in December 1820, Comet experienced groundings at Ardgour and Corpach before continuing to Oban in an unseaworthy state.

Following repairs, Comet set sail once again on 15 December 1820 but was soon wrecked at Craignish Point. The ship is believed to have split in half just west of Crinan. A navigational error had caused it to run aground in the fast tidal waters of the Dorus Mor

Thankfully, Comet was carrying no passengers at the time of its loss, apart from Henry Bell himself. He and the crew managed to scramble safely ashore. They could only watch as their ship disappeared beneath the waves. But it was not the end of Comet‘s story.

Discovery and designation

Fast forward to the 21st century and more than three years of research and exploration by a small group of Argyll researchers. They were able to establish the facts behind the Comet‘s final voyage and pinpoint the location of the wreck.

The Dalriada Dive Club in Oban confirmed the discovery before we were invited to assess the site for designation.

A dive survey by our underwater archaeology contractors Wessex Archaeology in September 2021 confirmed that the visible remains of the wreck which survive on the seabed are likely to be from the front half of the ship. These include the engine assemblage, possible flue and paddle shaft. Further elements of the wreck are likely to survive nearby.

There are very few examples of pre-1820 steam ships known in the UK. The remains of the Comet are therefore extremely rare and merit further detailed study and protection.

Shipwreck sites would normally be designated as historic marine protected areas but this time we decided to designate the wreck as a scheduled monument, at least as an interim measure. This status means that visitors can dive on the wreck but must not disturb it or remove artefacts without our consent.

A tragic ending

A monument to Henry Bell in Rhu Old Parish Graveyard, where is buried. (© HES Betty Willsher Collection, zoom in on Canmore)

And what of Henry Bell? He didn’t lose his drive after the loss of Comet. Soon after the accident, he commissioned a second steam ship, simply and appropiately named Comet II. Sadly, it was to have the same fate as it’s predecessor – and this time in tragic circumstances.

On 21 October 1825, Comet II was nearing the end of a journey from Inverness to the Clyde. Near Gourock, in the dark, it collided with another steamer, the Ayr. Comet II was badly damaged and sank quickly, giving the 80 passengers little chance to make an escape. 62 people were killed.

The sinking was descibed by the Scotsman as “a horrible calamity” in which those who lost their lives were “in the superior ranks of life.” It would prove to be the beginning of the end for Henry Bell.

Distraught, he abandoned his steam dreams and moved onto other projects, achieving little success. He died in Helensburgh in 1830, aged 62 and largely penniless. But Bell’s legacy was not forgotten. In 1872, a monument was erected beside the Clyde in Helensburgh commemorating “the first in Great Britain who was successful in practically applying steam power for the purposes of navigation.”

Explore Unpath’d Waters

You can uncover more stories like that of the Comet on the Unpath’d Waters Portal.

Part of the Towards a National Collection programme, the portal collates maritime data and records from different UK heritage organisations. It means we can search and analyse marine heritage like never before. The sea holds many heritage secrets – feel free to dive in!

For more seafaring on the blog, check out the treasures of Trinity House or the adventures of John Paul Jones.

The authors wish to acknowledge the major contribution of researcher Tony Dalton, who coordinated the search, Glasgow Museums, and John and Joanne Beaton, of Dalriada Dive Club, in this work.