If you’re lucky enough to have travelled around Scotland, there’s a good chance you were following in the footsteps of Anne Lister, known today as ‘the first modern lesbian’.

She left behind an extensive diary record of her life, detailing her business interests, intellectual pursuits, love life, and travels, parts of which were written in code.

Anne grew up in Yorkshire and in 1826 she inherited Shibden Hall in Halifax. She lived there with her father and aunt, but longed for a long-term romantic partner. In the TV series Gentleman Jack (2019), we see Anne ultimately settling down with Ann Walker.

However, before this, Anne was considering a partnership with Sibella Maclean, the daughter of the Laird of Coll in the Inner Hebrides. Sibella’s lineage and wealth were attractive to Anne, who aspired to move in more exalted circles. Anne wrote, ‘I would rather spend my life with Miss Maclean than any one.’

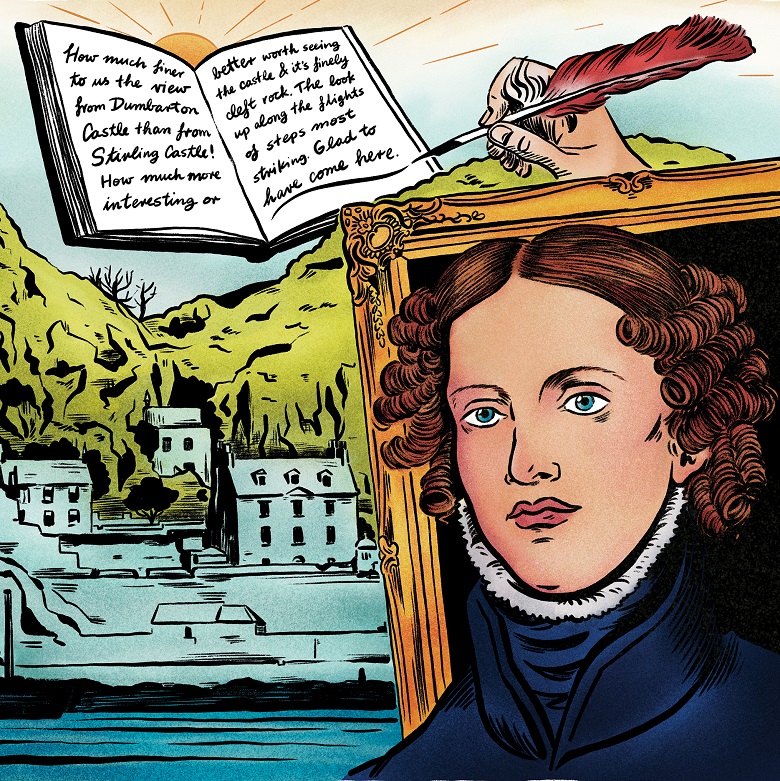

Anne Lister was full of praise for Dumbarton Castle. Illustration by Jules Scheele.

A romantic getaway

On 19 May 1828 Anne and Sibella met in Edinburgh to embark on a tour of Scotland together. Anne was exceptionally well-travelled, having already been to France, Wales, Ireland, Italy, and Switzerland.

With an interest in history and nature, Anne and Sibella visited many of the properties in our care. Some excursions required a degree of physical exertion considered unladylike, which Sibella was not well enough to undertake. Anne noticed that Sibella was ‘looking miserably thin and ill and aged with a bad cough’.

Defeat the seat!

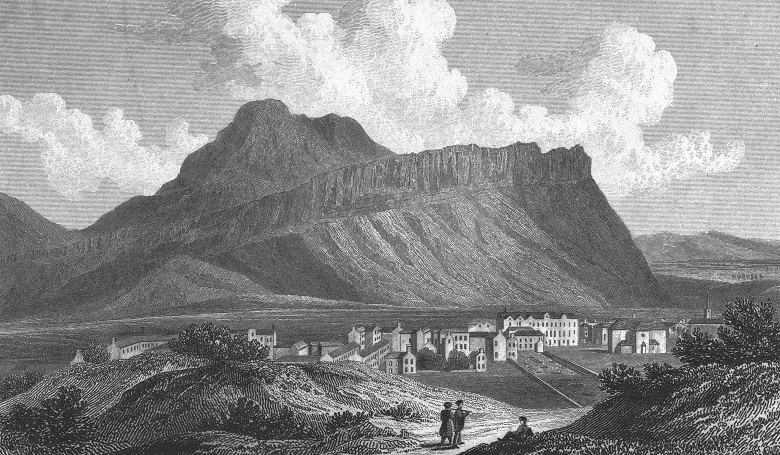

An engraving from 1829 showing view of Salisbury Crags and Arthur’s Seat copied from ‘Views in Scotland’. Drawn by W Westall, A.R.A.; Engraved by J. Fife. Zoom in on the detail in Canmore.

Anne went to Holyrood Park in Edinburgh with a Miss Sarah Riddell and they walked ‘all along the Radical walk (lately made) under the Salisbury crags’. Leaving Miss Riddell behind, Anne went on up Arthur’s Seat alone:

got to the top in 10 minutes, as fast as I could. Wind very high, dared not stand but sat a while on the topmost crag admiring the fine views all around me. Well worth the trouble, amply repaid. No traveller should miss it. The city as on a map at my feet. The firth of Forth very fine. Descended in 10 minutes right down in a straight line down the crag, never dreaming of its being so bad. Ladies should not attempt it but go round.’

Doing Dumbarton

Some properties visited by Anne and Sibella were still in use, like Dumbarton Castle, which was a garrison fortress. Again, Anne showed her physical energy:

A soldier shewed us round, mounting up the steps along the natural cleft in the rock. Very fine. 280 steps up to the barracks (which will hold about 106 or 130? men. Only 17 there now of the 1st foot (royals)) & 100 steps more up to the flag-staff, or the highest point of rock, over the Clyde & near to what they call Wallace’s Tower […] Then mounted the point over Dumbarton. Very fine view. Then a little higher to the powder magazine. Then on the highest & flag-staff point (flags always hoisted in Scotland on a Sunday). Very fine view.’

An oil painting landscape of Dumbarton, by Alexander Brown. It depicts the town in around 1820. The town’s famous glassmaking cones dominate the skyline. Dumbarton Castle can be seen perched on the rock in the distance. © West Dunbartonshire Council. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

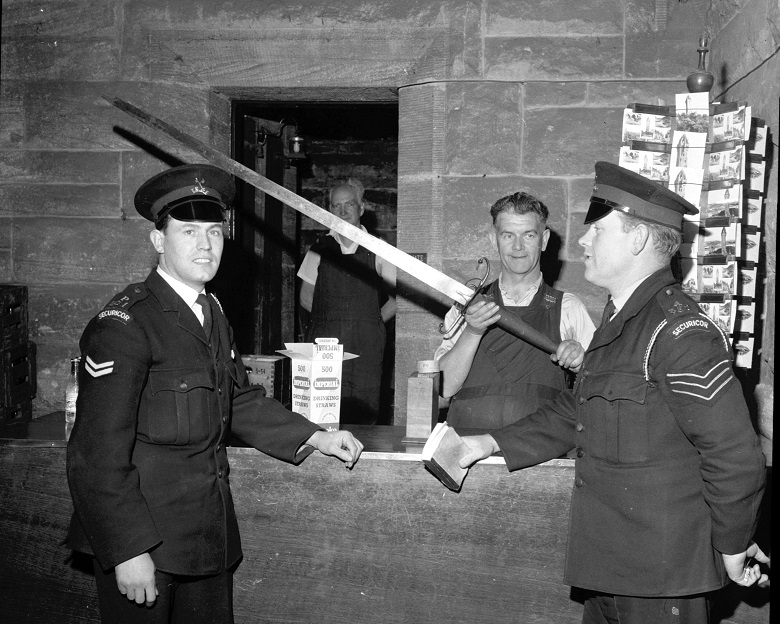

They also saw William Wallace’s possible sword, which, before the construction of the National Wallace Monument in Stirling, was held at Dumbarton:

Steel, 5 feet 4 inches long, tho’ unfortunately shortened by 9½ inches about 17 years ago by a Miss Fisher of Glasgow who, being considered a very strong lady, was trying to balance the sword on its point on her hand (the arm stretched out) & did so, but let it fall & thus broke off the length above named.’

Two security guards from the Securicor company arrive to collect the sword from the the National Wallace Monument on its way to an exhibition in Glasgow in August 1964. © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

A grim sight in Glasgow

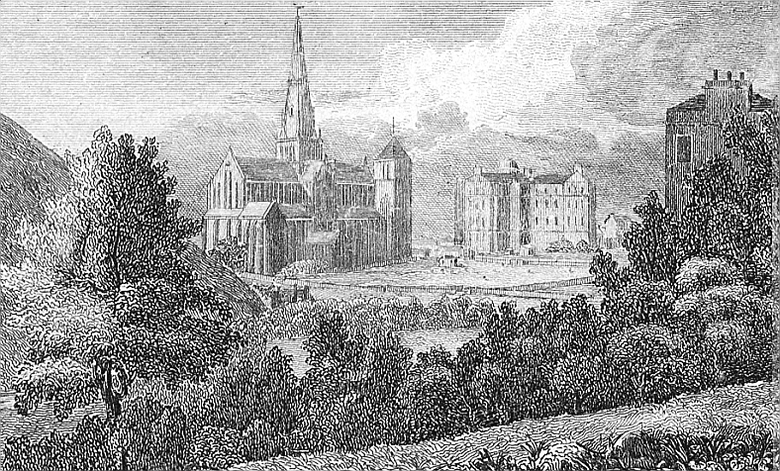

Another site still in use was Glasgow Cathedral, where Anne and Sibella attended a service. Some two hundred years earlier, the church had been divided into three for use by different congregations. Anne noted that, despite the beautiful surviving medieval architecture, one section ‘seems somewhat neglected & in ruin.’

The exterior of the building shewing broken windows & every species of want of repair & taste & care. It put me out of patience with all puritanism & Scotch Presbyterianism.’

An engraving of Glasgow Cathedral in 1833. This image is from ‘Scenes in Scotland’, by James Harris Brown. © Glasgow City Libraries. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Anne was not alone in thinking Glasgow Cathedral ‘the most melancholy thing I have seen in Scotland.’ There were growing calls for its restoration, and in 1835 two of the congregations were moved elsewhere, allowing removal of the interior dividing walls. In 1857 the cathedral came into state care and further improvements were carried out, including re-glazing the windows and replacing the roof.

The riddle of Sueno’s Stone

Most of the properties in our care that Anne visited were castles or religious sites. One of the few early medieval attractions that she saw was Sueno’s Stone in Moray. This Pictish monument bears carvings of a Christian cross and the scene of an unknown battle. Anne interpreted these as,

A sort of continued running pattern on the side towards Findhorn. On the other an indistinct time-worn story of some sort. A shaking of hands. A company of Highlanders? Men with kilts and highland bonnets.’

To this day the carvings remain mysterious, possibly depicting conflict between the Picts and Vikings, or the absorption of Pictland into the kingdom of Alba by Cináed mac Alpín in the 9th century. Take a very close look at Sueno’s Stone in 3D on Sketchfab.

On 1 August Anne and Sibella parted ways, planning to spend the winter together in Paris. Sibella remained at her brother’s home, Aros House just across the bay from Tobermory on the Isle of Mull, while Anne continued travelling.

Bagging the Borders abbeys

Anne visited the Borders abbeys of Melrose, Dryburgh, Jedburgh, and Kelso. She was particularly struck, at Jedburgh, by the parish church which had been built into the nave of the abbey church:

Very large remain. The largest I have seen. Larger than Melrose. Finer? if seen to advantage. Too much choked up. The church in it spoils it.’

An engraving of Jedburgh Abbey in 1776. The small church, which Anne Lister was scathing of, is depicted in this illustration. Take a closer look on Canmore.

This church had been built by 1671 but, later in the nineteenth century, it was dismantled, and the abbey church more closely resembled its original state. Despite Anne’s disapproval, she bought a picture of the abbey at a local bookseller’s shop and her friend, a Mr Renwick, gave her ‘an egg cup made of the tree that grew in the abbey’ in 1523, when English forces attacked.

A sad parting of ways

By 15 August Anne was back home at Shibden Hall. Instead of meeting Sibella in Paris that winter, Anne visited former partner Mariana Lawton at Lawton Hall in Cheshire while Sibella sought treatment for tuberculosis in London.

The last time Anne and Sibella met was in London in March 1829. Sibella died on 16 November 1830. Anne wrote,

She is the 1st friend I have ever lost – I know not quite what is my feeling, but it is one of great heaviness, and heart-sinking, tho’ I know that her release was a mercy, and what all must have desired’.

Anne moved on and in 1834 took the sacrament with Ann Walker, symbolising their marriage. Lister continued to travel, to Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. She died at Kutaisi in Georgia on 22 September 1840.

Anne Lister did many of the things that we as tourists do today: found out about the histories of the sites, enjoyed their views, and sought out souvenirs. She also showed considerable concern for the conservation and preservation of historic structures. All of these things she noted in her diaries, allowing us to catch a glimpse of her captivating life.

More reading

All of Anne Lister’s Scottish tour diaries are online.

Head to Knightlab for maps of Anne Lister’s Scottish tours. Part one traces from Edinburgh to Rothesay. Part two explores Rothesay onward. With thanks to A Leigh Mitchinson, Amanda Pryce and Janneke van der Weijden.

Read more in this paper by Kirsty McHugh, ‘Sightseeing, social climbing, steamboats and sex: Anne Lister’s 1828 tour of Scotland’, Studies in Travel Writing 22 (2018).

Take a look at Morag Cross’s blog about the Campbells if you’re interested in women who were bucking social conventions in the early 1800s. The Campbells appear in Lister’s diaries where she mentions them as fellow visitors to France and Switzerland, although it seems they never actually met. She was also aware the Campbells had moved to Scotland in 1828.

If you’re keen to follow in the footsteps of Anne Lister, you could save money on your history hunting with a Historic Scotland Membership.