When Harry Whyte died in an Istanbul hotel in 1960, few people would have noted his passing.

A journeyman reporter, Harry worked in his native Scotland, England, the Soviet Union and Turkey. Yet Whyte, the son of a house painter from Edinburgh, occupies an interesting position in the LGBT rights movement, but not in Scotland. In fact, Whyte campaigned for the acceptance of same-sex relationships in the Soviet Union during the 1930s. Whyte was ‘the Scot who challenged Stalin’.

Early life in Edinburgh

Harry Whyte was born in Edinburgh in 1907. He had a working class background – his father was a house painter. However, Harry was accepted to George Heriots on a scholarship and attended the fee-paying school between 1914 and 1923.

The George Heriots blog recounts that:

His pupil entry records states that he excelled in subjects he was interested in but careless in the rest. From his reports, he excelled in English, History, French, Russia, Economics and Geography.”

Whyte was a pupil of George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh. Zoom in for a closer look on Canmore.

Harry left school after securing a job with the Edinburgh Evening News. It seems that the General Strike of 1926 galvanised Harry’s interest in radical left-wing politics. The strike lasted 9 days, from 4 to 12 May. It involved key industries, such as public transport, building and printing, taking industrial action to support the miners’ protest against government plans to increase hours and lower pay.

A group of miners passing the time with a game of cards outside Prestonpans Colliery, East Lothian, during industrial action at the time of the General Strike. © Hulton Getty. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Leaving his old life behind

Harry joined the Independent Labour Party soon after the strike. He moved to London in 1931, and while there he joined the Communist Party of Great Britain.

From London, Whyte moved to the Soviet Union, taking up a position with the Moscow Daily News. While in Moscow, Whyte began a relationship with a local man. However, after Stalin’s recriminalisation of homosexual acts, his lover was arrested during a public clampdown on ‘sexual immorality’.

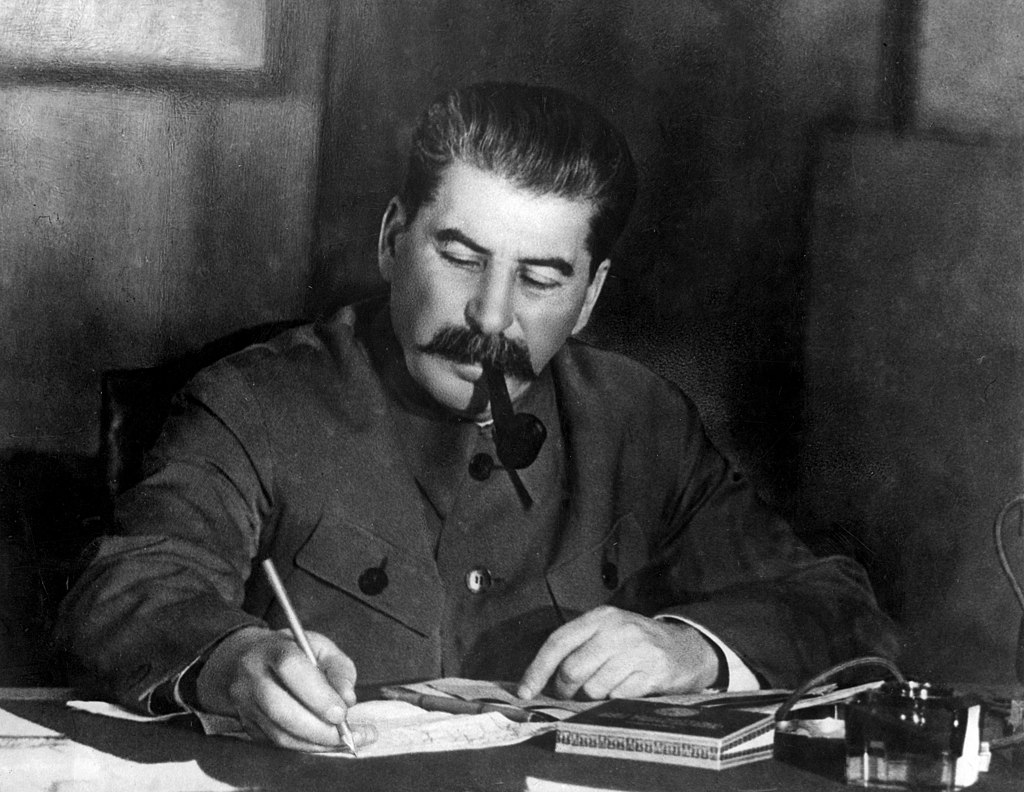

This arrest, coupled with Whyte’s growing unhappiness with Stalin’s increasingly vice-like grip upon Soviet society, prompted the Scot to write a lengthy letter to the Soviet leader. Whyte argued that homosexuality was conducive to communism. Harry’s full letter stretches to nearly 4,500 words and can be found in full on the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty website. This section from the introduction to his letter provides a flavour of what Whyte had to say to Stalin.

To Comrade Stalin

Although I am a foreign communist who has not yet been promoted to the [All-Union Communist Party] I nevertheless think that it will not seem unnatural to you, the leader of the world proletariat, that I address you with a request to shed light on a question that, as it seems to me, has huge significance for a large number of communists in the USSR as well as in other countries.

“The question is as follows: can a homosexual be considered someone worthy of membership in the Communist Party?

“The recently promulgated law on criminal liability for sodomy […] apparently means that homosexuals cannot be recognised as worthy of the title of Soviet citizen. Consequently, they should be considered even less worthy to be members of the AUCP.

“Since I have a personal stake in this question insofar as I am a homosexual myself, I addressed this question to a number of comrades from the [Joint State Political Directorate] and the People’s Commissariat for Justice, to psychiatrists, and to Comrade Borodin, the editor-in-chief of the newspaper where I work.

“All that I managed to extract from them was a number of contradictory opinions which show that amongst these comrades there is no clear theoretical understanding of what might have served as the basis for passage of the given law.”

Harry Whyte was born in Edinburgh, but soon left it behind. The journalist lived and worked in the Soviet Union, Morocco, and Turkey amongst other places, attracting the attention of secret services. Illustration by Jules Scheele.

The aftermath of the letter

Stalin was unconvinced by Whyte’s argument, sending it to the archives with a scribbled note, ‘an idiot and a degenerate’. Stalin’s dismissal of Whyte’s pleas for tolerance marked an end to his stay in the Soviet Union.

Whyte returned to Britain unaware that he had been monitored by the British intelligence services for a decade, an interest that would continue until his death.

By the spring of 1938 Whyte was again on his travels, this time to Morocco where he engaged in low-level spying on German and Italian nationals for the British Tangier Secret Intelligence Service.

Wartime

In December 1941 Whyte was called up, achieving a position as a temporary acting leading coder on the Arctic convoys. His fluency in several languages outweighed any concerns over his communist sympathies and homosexuality.

However, when the war ended the British intelligence services resumed their monitoring of Whyte. His dissatisfaction with the direction of communism, and his frustration with legal sanctions directed at homosexuality might explain his constant movement. By 1950, he was working for Reuters as a freelance correspondent in Turkey.

Life on the Move

Whyte never appeared comfortable as a gay man living in Britain. Interestingly, he was more open about his sexuality whilst living in a nation governed by a dictator. In Tangier and Ankara he was much more confident and relaxed, involving himself in LGBT circles.

Family members knew very little about Whyte’s life and when he died in 1960, aged 53, mystery surrounded his demise. Some family members believed he had been shot for spying, others that he had taken his own life.

In fact, Harry died suddenly while attending a social event in Istanbul. He left an estate of just £1 to his Turkish partner and was buried locally.

Whyte is an almost unknown figure in the history of LGBT rights, but his courage in challenging Stalin over homosexuality, and the great personal risk he took advocating sexual liberty under communism positions him as one of Scotland’s earliest LGBT rights advocates.

Explore more LGBTQI+ History

Read more LGBTQI+ history on our blog.

Watch as Jeff Meek and Amy Tooth Murphy discuss the unheard histories, triumphs and tragedies of Scotland’s LGBTQI+ past in this livestream from 2021.