When the time comes for that well-earned break, you could go big in a cavernous hotel or city-sized cruise ship, but what about getting away from it all somewhere small?

Holidaymakers in Scotland have a wealth of different options to choose from, but as our recent Engine Shed blog post about Grassroots Hutting has indicated, the perfect dimensions for that vacation could be more compact than you think.

Whether made of wood, stone or canvas these cosy retreats have been granting people the chance to escape the daily grind for generations.

So, pack your (smallest) suitcase and join us on a whistle-stop round up of tiny tourism. We begin with that classic one-room Scottish option; the bothy.

The Munro, Carn na Caim, seen from a bothy by Loch Cuaich in summer. At 941m, Carn na Caim is the highest point on the large plateau which extends north-east from the Pass of Drumochter to Loch an y-Seilich. © Ruaridh Pringle. Licensor SCRAN.

‘Your Comforts Have to Be Carried In’ – bothy life

Bothies can be found around the United Kingdom, but they are synonymous with Scotland. These modest shelters are small, squat and stone. You won’t find any indoor plumbing or electricity, and very few have a sleeping option that is more glamorous than a simple shelf, if you’re lucky.

Today, bothies are favoured by hardy hillwalkers looking for an option that isn’t a tent, but they have a long history inexorably linked with seasonal labourers who used them as temporary accommodation when working the land, or the water.

A fisherman’s bothy at Fascadale, Ardnamurchan parish, Argyllshire, pictured in 1982. This seasonal salmon station attracted short-term migrants to the area, with fixed poles at left to dry nets and ropes. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor SCRAN.

For those near lochs or the coast, the start of spring would herald the arrival of fishermen carrying wooden kists (chests) containing clothes and food they needed for the season. Many of these bothies had smokehouses attached, where the workers would prepare the catch for transport, as the tools of their trade (nets, floats, ropes) were outside, drying in the sun.

Away from the coast, agricultural workers followed similar patterns, where bothies were introduced as an economical means of housing single male farmworkers (so-called ‘bothy lads’). From the 18th century to the interwar period, these labourers worked the land during the day and played games or musical instruments in the evening. The farmer would provide them with a basic daily allowance, typically oatmeal, milk and hay for their mattress.

A carefully-posed group of unidentified ‘bothy lads’, photographed at Balmyle Farm near Meigle in Perthshire in 1930. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor SCRAN.

In the mountains, bothies took on a new role in the 19th century with an increase in the popularity of sport shooting. Enormous estates constructed stone shelters for deer trackers to use in between supervising those out on the hills. Many were then reclaimed by mountaineers and walkers once the stalking season closed.

The most famous example, and the oldest bothy still in use today, lies in the middle of the Lairig Ghru, the pass that runs between Aviemore and Braemar in the Cairngorms. Built in 1877, Corrour Bothy was abandoned in the 1920s but rescued and renovated, then enlarged and fitted with a toilet in 2006.

Its single room, measuring 6m by 4m (20ft by 13ft) is well-used by walkers and climbers today, and those who stay have the opportunity to add their thoughts and experiences to the collection of bothy visitor books, with entries dating back to 1928.

The Corrour Bothy on the Mar Lodge Estate, photographed in 1995 before the right-hand gable wall was removed and the bothy extended with a dry toilet. The bothy was so popular that wild toileting had turned the area around it into an ‘environmental hazard’ according to the Mountain Bothies Association. © National Trust for Scotland. Licensor SCRAN.

‘On-site facilities consisted of a climbing frame by the bins’ – the caravan

To many people, the first thing that springs to mind when thinking of a small holiday space is the quintessentially British caravan. Typically, they are either pulled behind a car (otherwise known as a ‘wobble box’) or fixed in place to the ground (the static caravan).

It was the latter of these that appeared first, morphing out of the seaside chalet movement (more on which in a moment). Advantages of the set caravan revolve around the location; somewhere you can keep returning to again and again, without having to haul it there yourself.

Static caravan site to the south of Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll, photographed in 1983. The site has since been enlarged and is open to this day. © RCAHMS. Licensor Canmore.

The changing nature of seaside holidays caused concern in Scottish resort centres from the 1960s onwards, and although traditional hotels and guest houses saw declining occupancy, caravan and campsites flourished due to their lower cost and increased flexibility.

These same factors also saw the enormous rise in touring caravans, which started to appear after the First World War. Modelled on their horse-drawn predecessors, their prohibitive cost declined after WWII when they became lighter and more durable, also becoming cheaper to buy or rent.

A 1932 Ford Model Y (registration GG 8832) towing a caravan, parked by the waterside of Loch Lomond in 1936. © Scottish Motor Museum Trust. Licensor SCRAN.

‘The outdoor pool was freezing, the chalets were basic, but there was plenty of food’ – the seaside chalet

Slightly larger than a static caravan, and considerably older in terms of their history, the chalet has been at or near the Scottish seaside for generations. Today, many campsites have rebadged them as ‘lodges’, but the concept remains the same – a small, multiroomed space mounted on a concrete base and fixed to the ground.

Originally, chalets were the Alpine equivalent of a bothy; small temporary residences used by livestock herders in the mountains of France and Switzerland, later repurposed by outdoor enthusiasts as overnight accommodation.

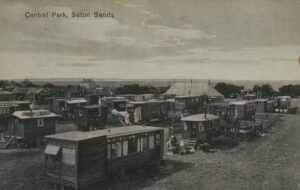

A 1930s black and white picture postcard of chalets arranged in rows at Seton Sands Camp in East Lothian, which was commissioned for sale in the camp store. The tent in the background was used for entertainments and Church meetings. © East Lothian Museums Service. Licensor SCRAN.

But here at home, following the Victorian-era popularity of beach huts, chalets became a common sight at holiday camps from the mid-20th century. One of the largest of these in Scotland is at Seton Sands in East Lothian, on a piece of beachfront land that has been welcoming holidaymakers since 1924.

Some chalet parks (such as Skateraw in Dunbar) used ex-wartime Nissan huts for their guests, but Seton Sands, founded by local farmer William Bruce, had over 600 chalets and caravans of various sizes, on a piece of land measuring 60 acres.

Its chalets were originally leased to holidaymakers from Glasgow during their July Fair holidays, but Seton Sands became popular with visitors from Edinburgh and nearer at hand for short stays or weekend breaks. By the 1950s, tenants were sufficiently secure in their tenure to improve the basic plots and even personalise their accommodations (within reason).

A well-kept chalet at Port Seton camp in 1949. Many holidaymakers from Glasgow and Edinburgh still spend the summer here, although huts like this one have since been modernised into static caravans or lodges. © Newsquest (Herald & Times). Licensor SCRAN.

‘It’s about keeping it in the scope of ordinary folk’ – hutting

As detailed on the Grassroots Hutting blog on the Engine Shed, the tradition of recreational hutting in Scotland goes back to the 1920s when people would seek to escape the heavily industrialised cities and towns for a return to nature.

After paying a landowner a small amount in rent for the permission to construct a small hut, entire families would arrive on the bus, sometimes bringing foundation bricks and timber with them to start the building process. Over time, a community would form in the woodland.

A man digs his vegetable patch outside a hut at Carbeth Hutting Community, Campsie Fells, photographed in September 1999. © Crown Copyright, HES. Licensor Canmore.

The largest hutting community in Scotland is on the western side of Carbeth Hill in the Campsie Fells, approximately ten miles north of Glasgow. The huts here formed a vital lifeline to people from Clydebank when it was devastated by an air raid in 1941, killing 528 people and making 11,000 homeless.

Today there are over 140 huts at Carbeth, most of which have no running water or electricity and with a wood-burning stove for heating and cooking. Other facilities are forged by the hutters themselves; between 1920 and 1972 a small burn was dammed to create a swimming lake.

More than 80 years after setting up the camp, in 2013 the Carbeth hutting cooperative secured a £1.75 million loan to buy the land on which their huts are located, keeping the tradition alive for generations to come.

When it comes to maintaining the traditional aspects of hutting, our grassroots hut at Comrie Croft was inspired by the history of people using materials that were local to them at the time to build retreats enabling them to re-engage with nature. It uses only materials sourced close by, such as turf and bracken, and was constricted using non-powered tools.

One of the threads that joins together the getaway places in this blog is their minimal impact on their surroundings, either due to their small size (huts, chalets) or the fact that they are movable (caravans, tents). The Comrie Croft grassroots hut has been designed to melt back into the land at the end of its life as a building, in a truly circular approach.

‘We were out in the night digging a trench around the tent to stop the rainwater coming in’ – camping

According to market research firm Mintel, in 2022 the people of the UK made an estimated 16.7 million camping and caravanning trips, a return to pre-pandemic levels (they also found that 69% of campers would prefer to pitch up somewhere with private bathroom facilities).

Speaking of pitching up, what the experts call the ‘standard grass pitch’ still dominates camping, as it has done since it first became popular. The romance of throwing all you need in a rucksack and going for a wander is still with us, even now.

A well dressed, but rather untidy camper sitting at his tent, Dunkeld, Perthshire, 1910. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor SCRAN.

From the nineteenth century onwards, many young men went on holiday on their own or in small groups. Many were attracted to a simple, pioneering lifestyle, helped in this pursuit by the growth in popularity and availability of the bicycle.

The ‘father’ of modern-day camping was Thomas Hiram Holding, author of the first edition of The Camper’s Handbook in 1908. As a trained tailor, he designed and made tents himself, and travelled throughout Ireland and Scotland becoming an authority on camping.

Glenmore Campsite, on the shores of Loch Morlich, in the Cairngorms, photographed in April 1968. Located near an ancient Caledonian Pinewood forest, Glenmore is about 5 miles SE of Aviemore. Licensor SCRAN.

As Camping Associations and the Boy Scouts and Girl Guiding movements became hugely popular, so too did camping holidays. Just like its spiritual (and less hardy) twin the caravan, when equipment became lighter and less expensive, more people took to the pastime.

Again, the rise in car ownership proved a boon for those wanting to find a place to camp, even if sometimes the facilities were less than glamorous. These days, the rise of ‘glamping’ has seen features improve, with Hipcamp reporting that the most requested feature are hot tubs.

A privy tent stands by the shore of a loch, unknown location, c. 1930s – 1960s. Licensor SCRAN.

With the massive popularity in music festivals and cheap pop-up tents, camping is here to stay. The Wild Camping movement is also very popular, with the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 giving people the right to pitch up pretty much wherever they choose.*

* However, this only applies to where access rights apply, and camping and staying overnight is not allowed at Historic Scotland properties. No camps should be made on or near a scheduled monument. We have a pdf guide on Wild Camping at Scheduled Monuments [pdf, 670KB].

Heavy rain floods Edinburgh’s Muirhouse caravan site in July 1961. © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor SCRAN.

Whether a yurt, tipi, pod, lighthouse, treehouse, boathouse, summerhouse, bell tent or wigwam, Scotland has no shortage of small spaces in which to escape the everyday. The appeal of these getaways is maybe just that; they are atypical and different from the square rooms most of us live in.

Small spaces are interesting, they aren’t just a place to stay overnight but a place to interact with. All of them make a holiday more memorable. Good times do come in small packages.