It is a bright, dry day in 1883 and there is a bustling little harbour backed by dramatic limestone cliffs. The sound of the waves in the Lyn of Morvern is punctuated by the occasional explosion of gunpowder and blast of stone.

Trundling carts are moving coal and wooden barrels packed with burnt limestone in and out the yard. Several men are layering coal and limestone into one of the massive, open topped stone kilns. The adjacent kiln is a giant, reeking chimney – black smoke fills the air above as men rake out a substance from the opening below.

This is An Sailean lime works on the northwest coast of the isle of Lismore, less than a 10km sail from the harbour town of Oban.

Lucrative lime

An Sailean from the cliffs above (this image and our cover image are © HES, Dr Colin and Dr Paula Martin Collection)

Lime works were a lucrative business in the 19th century and offered vital employment to labourers. Records from the Napier Commission of 1883 state that 12 to 16 quarrymen and lime burners were employed at An Sailean.

Lime works were the source of a vital product for both industrial and agricultural Scotland. Burning limestone, which is calcium carbonate, produces calcium oxide. Mixed with water this produces slaked lime – calcium hydroxide. Slaked lime added to the land raises its pH (level of acidity or alkalinity) and improves the fertility of the soil. It was vital to the agricultural revolution which helped feed the growing and ever more centralised populations.

Lime was also necessary for the development of Scotland’s towns, cities and infrastructure as it was a key component in mortars and plasters and was also used in numerous industries such as steel making.

Limeworks on Lismore

An aerial image of An Sailean (© HES, Dr Colin and Dr Paula Martin Collection)

The first documented kiln on Lismore is dated to 1804 but the extraction of limestone and burning to produce lime here dates back well beyond the 19th century.

The lime industry was active on the island in the 18th century, with the Statistical Account of 1791 stating ‘burning of lime for sale has been begun… in Lismore and Appin’. The lime kilns at An Sailean are depicted on the Ordnance Survey First Edition map, drafted in 1871. However, the works were in operation from at least the mid-19th century.

There are eight historic industrial lime works sites on the Island of Lismore. All have a similar topographic location and set up. They are all on the coast with kilns located below a quarry on higher ground so processing would be gravity-fed. Often they would have a quay for the unloading of coal and export of lime.

The lime produced on Lismore was used for major developments like the Caledonian Canal and private constructions such as Kinloch House on Rum. It is highly likely lime from Lismore was used in the construction of houses and streets in west coast villages and for urban expansion in the area; one example being the booming harbour town of Oban.

An Sailean

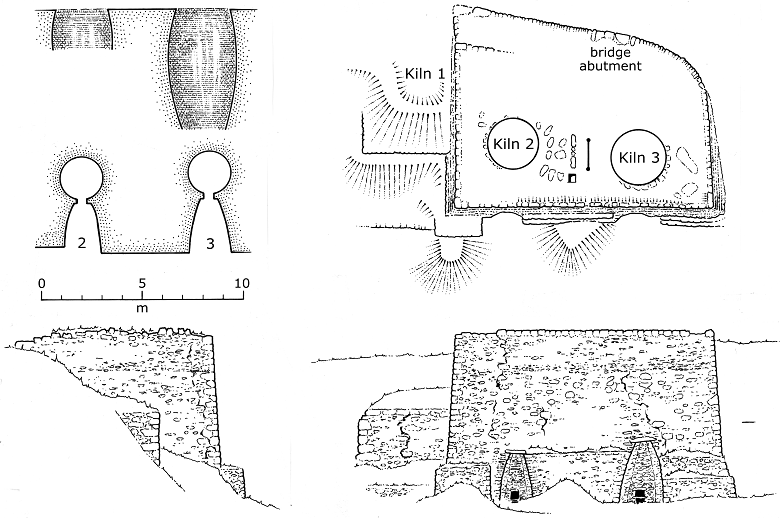

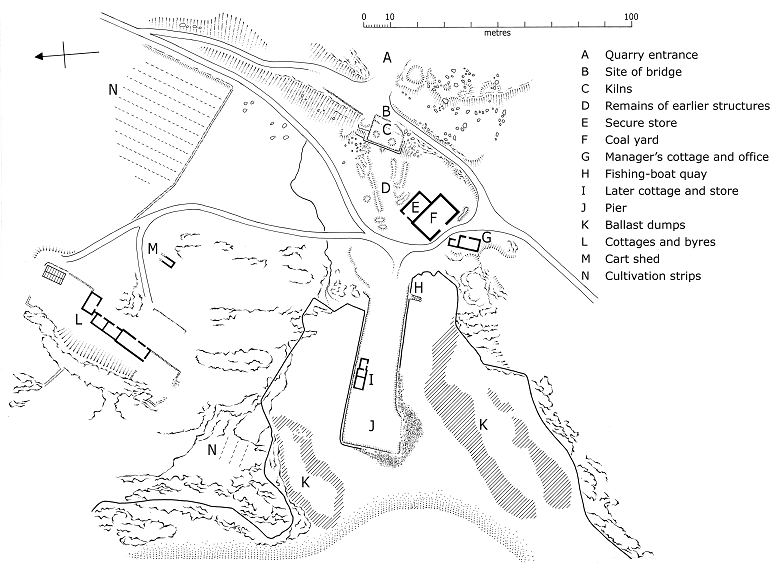

Survey plan of An Sailean lime works – zoom in on Canmore (© HES, Dr Colin and Dr Paula Martin Collection)

An Sailean was the largest lime works on the island and the last to operate, only closing down in the 1930s.

Today the site is a quiet spot. The buildings are abandoned and stand as a silent reminder of its industrial past. However, the remains are extremely well-preserved and archaeologists have recorded and mapped the site.

Visible today are the lime kilns; limestone quarry; managers’ house with office; coal store with yard; associated workers’ cottages; explosives store; a quay with shop and cottage, adjacent to ballast dumps from ships.

A photographic record

An Sailean lime works in 1883 (© HES, Erksine Beveridge Collection)

In fascinating accompaniment to our 2023 site visit and existing archaeological survey records, we also happen to have historic photographs of the lime works in operation. These images were taken in 1883 by Erskine Beveridge (1851-1920), a Scottish textile manufacturer, historian and antiquarian.

They provide a rare visual record of the site in operation. His images taken at An Sailean show all the buildings roofed and in-use alongside a busy quay with several vessels docked. Through this photography it is possible to tour the site and imagine what it was like when Erskine Beveridge visited.

A visit to An Sailean

Approaching from the northwest, we walk down a gravel track leading into An Sailean. On our right is a cart shed sat in a little field growing crops like potatoes, kale and maybe some grains.

At the far end of the field is a row of very old cottages, now split into two more comfortable family homes for the lime workers. At the end is a relatively new detached stone cottage with neater built walls, bigger windows and roomier ceiling heights inside. All evidence of “modern” Victorian living.

The later lime worker’s cottage at An Sailean (© HES)

Moving down the track and glancing to our left, we see the massive limestone quarry face rising 50 metres into the sky. The grey, towering cliffs have been blasted by decades of quarrying to collect stone for the lime burning process.

Straight ahead, at the foot of the quarry, are two massive stone-built structures. Set into the slope and rising over 8.5 metres high at the front – these are the beating heart of the site – the lime kilns. Here the broken limestone was burnt between layers of coal in a massive pot-style chimney.

Belching noxious fumes and black smoke, the kilns were heated to around 900 degrees Celsius. The calcified lime is collected through a small, grated opening at their base.

The Manager (and the Merchant)

The track bears to the right slightly beyond the kilns and downslope, and we see a neat little building ahead. It looks like a two roomed, stone-built cottage with a small lean-to on the right. This is the manager’s house and site office – located right in the busy hub of the lime works.

From around 1850, the site manager John McIntyre, also operated as an independent coal merchant. His yard and store at the site served the entire island with fuel. This nice little side business helped make John a wealthy man!

Across the track, opposite the office is a roofed storage building and a secure yard. Originally it had high, locked gates and metal railings atop the walls. This was where the valuable coal was stored and processed lime was kept safe and dry before exporting.

The rear of the manager’s house and office in 1883 (© HES, Erksine Beveridge Collection)

The Hub at the Harbour

Turning towards the sea, the little harbour sits before us with a large stone quay projecting into the water. This would be full of sailing ships and one steamship; some offloading coal, others taking on barrels of slaked lime.

Halfway along the quay stands a little building which was likely a worker’s cottage. It also served as a tiny shop. This harbour was a crucial part of the site. Coal would be shipped in, with vast amounts required when burning limestone.

The quay provided a platform for the lime product to be shipped out to the west coast of Scotland. The vessels used for exporting the lime had to move such great volumes that they arrived at An Sailean with stone ballast for weight. They dumped these into the sea at the end of the quay as they took on fresh barrels of lime.

The busy quay and cottage with shop in 1883- (© HES, Erksine Beveridge Collection)

Finishing with a bang

There is one small part of the lime works yet to be seen on our tour. A couple of minutes stroll down the next estate’s path brings us to a small, stout stone building. Located at the foot of the limestone crags, it has one small doorway and no windows. It is only a couple of metres in length and breadth with a low stone wall circling it.

This is the An Sailean explosives store! Gunpowder used to blast the limestone cliffs had to be kept safe, dry and well away from the busy site to minimise risk of accidents. A stark reminder of one of the many dangers of the industry.

The small and sturdy explosives store (© HES)

Designating An Sailean

Every aspect of the original lime works of An Sailean can still be seen today. It’s an enduring monument reminding us of a time past. You can walk through the remains and easily visualise and try to experience the once bustling industrial site. The site is silent but its physical remains speak volumes.

In early 2024, we designated the remains of the lime works as a Scheduled Monument and a Listed Building. This recognises their national importance and special architectural and historic interest. Approaching 100 years since the lime works were closed – An Sailean is now proudly back in the limelight.

The manager’s house as it appears today (© HES)

Today’s view from the yard to the kilns with quarry behind (© HES)

You can see a wealth of images of An Sailean over on Canmore, plus there’s more remarkable industrial sites on the blog, such as Blackcraig Lead Mines in Dumfries and Galloway or Caerlee Mill in the Borders.