In 1820, Scotland was a particularly turbulent place. It was during this period that what has variously been described as ‘the Radical Rising’, ‘the Radical War’ and/or ‘the Scottish Insurrection’ took place.

One confrontation in this ‘Rising’, the ‘Battle of Bonnymuir’, occurred near Stirling Castle and saw its final, lethal, repercussions played out in the Castle and town of Stirling.

Background of the Radical Rising

The early 1800s in Scotland gave rise to much discontent. The 1815 Corn Laws, a measure designed to maintain high food prices, led to food riots when the price of grain doubled. As food prices were raised, wages fell, especially after the Napoleonic Wars in 1816. An estimated 300,000 men were demobilised from the army leading to surplus labour, mass unemployment and lower wages. Despite the end of the war, however, taxation remained high. Such economic and social unrest led many to question the whole political system and call for its reform. At the time in Scotland only about 0.2% of the population had a vote.

Discontent had manifested itself globally throughout the 1700s. But it was an English massacre that did much to set the scene for the 1820 ‘rising’. The Peterloo Massacre, which took place in Manchester in August 1819, saw a reform meeting of around 60,000 charged by the cavalry. This resulted in 15 people killed and around 700 injured. Protest meetings occurred throughout Scotland. The authorities responded with the ‘Six Acts’ making it easier to suppress, discover and punish discontent.

This sticker was made in 1846, some 20 years after the Radical Rising.

1820 – ‘Battle of Bonnymuir’

The 1820 event which has most resonance for Stirling and the Castle happened 4-5 April and culminated in the ‘Battle of Bonnymuir’. On Tuesday 4 April a group of armed men gathered in Glasgow. They were advised to march to the Carron Ironworks in Falkirk and take possession of the weapons there.

Andrew Hardie, the ex-military group leader, was told to rendezvous with another radical commander, ex-military man John Baird, in Condorrat. Hardie and Baird had only about 30 men but were persuaded by John King to continue to Carron. King assured them that he’d pick up more men on the way. As they approached the village of Bonnybridge they met again with King who said support was on the way and that Baird and Hardie were to leave the road and wait at Bonnymuir.

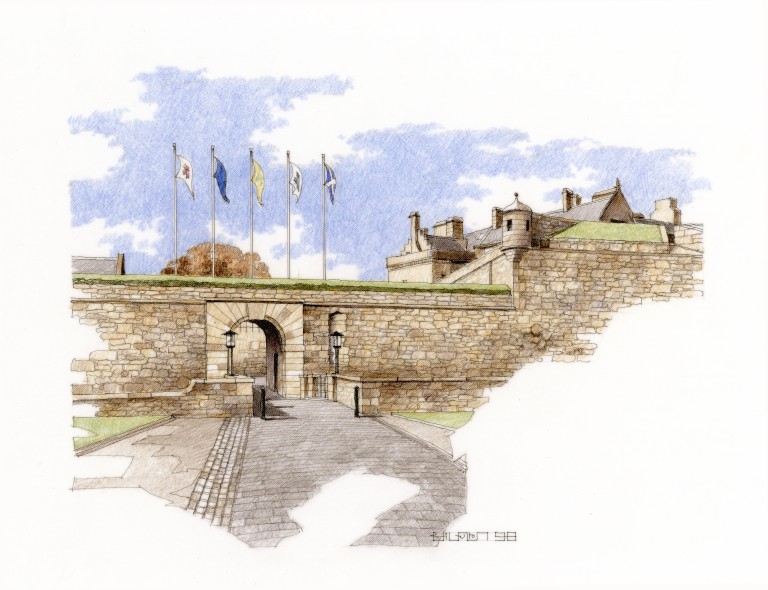

Coincidentally, the authorities had already sent a regiment to the Carron works and another group of troops had left Perth for Carron, via Stirling Castle. The Perth troops, having met up with the Stirlingshire Yeomanry at Kilsyth, converged on the Bonnymuir. After a short battle, they overcame the radicals. Eighteen men were taken prisoners and marched to Stirling Castle.

Members of the Radical Rising were marched to Stirling Castle.

Imprisonment

Once at Stirling Castle, Baird assumed the leadership of the group. The prisoners were held in cells off the Lion’s Den, usually identified as the vaults under James V’s Palace.

The vaults under James V’s Palace were probably where the prisoners were held.

Baird, however, as leader, was held separately in the ‘dungeons’, possibly in what is now the Green Room under James IV’s Great Hall. The prisoner’s confiscated weapons were also brought to the Castle. Comprising of 5 muskets, 2 pistols and 18 pikes they were stored in 2 sealed chests in a room below the staircase of the Castle’s Ordinance Store. This was possibly in the northern part of James IV’s King’s Old Building which was burnt down in 1855.

On Saturday 8 April, the prisoners were taken by steam boat from Stirling to Newhaven and, from there, to Edinburgh Castle for interrogation. They returned to Stirling by steam boat on June 21 to be held in the Castle during their trial. While at Stirling Castle the letters of the prisoners were smuggled out by a local woman, ‘Granny’ Duncan. She lived between the esplanade and the Ballangeich Road and provided porridge to the prisoners.

Trial and Execution

The Court opened at Stirling on 13 July with Andrew Hardie tried first. After a day-long trial the jury considered Hardie guilty of 2 counts of treason.

The Inner Close at Stirling Castle where Baird and Hardie said farewell to the other prisoners

The next day John Baird was likewise found guilty. On 15 July James Cleland changed his plea to guilty, followed by the remaining Bonnymuir prisoners. On 4 August the 18 Bonnymuir men were sentenced to death. This was later commuted to transportation for life for most of the prisoners with only Baird and Hardie being hanged and beheaded.

Friday September 8 was the date fixed for execution of Baird and Hardie. Two weeks before their execution they were placed in the same cell at Stirling Castle. The morning of the execution, they were allowed to say farewell to the other Bonnymuir prisoners in the Castle’s ‘courtyard’, possibly the Inner Close of the Castle. They were then led down from the Castle to Broad Street where the scaffolding was erected before Stirling Jail and an estimated crowd of 2,000 waited to witness the execution.

Despite the Sheriff of Stirling, Ranald MacDonald, requiring that they made no political speeches both Baird and Hardie’s speeches declared that they died ‘for the cause of Truth and Justice’. They were then hanged and beheaded. Their bodies were buried in a single grave outside Stirling Castle.

You can still see the very robe the executioner wore if you visit The Stirling Smith

Aftermath

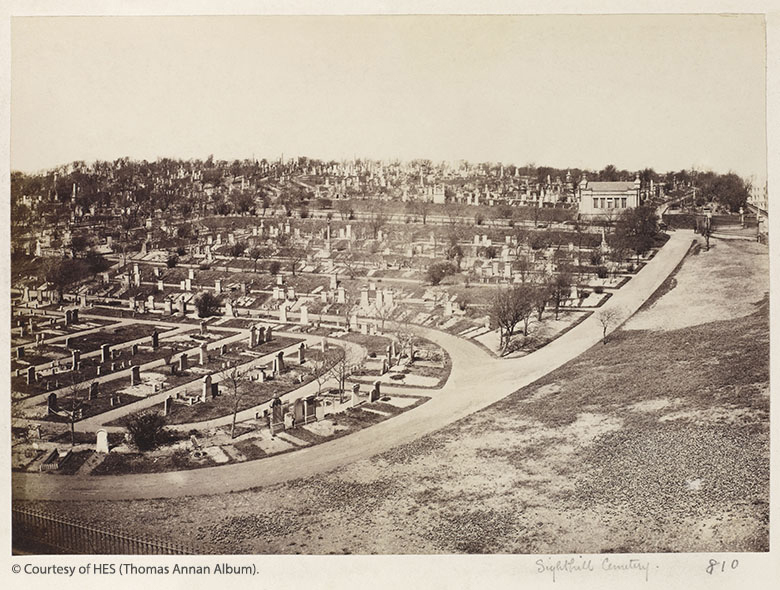

In 1847 Glasgow radicals got permission to rebury Baird and Hardie’s bodies in Sighthill Cemetery in Glasgow with an inscribed monument. The site of their execution in Stirling is now marked by a plaque.

John Baird and Andrew Hardie were re-interred at Sighthill Cemetery the same year the monument was built. The monument is also dedicated to a third radical, James Wilson.

It has been suggested that Sir Walter Scott’s ‘plaided pageantry’ associated with the 1822 royal visit of George IV was an attempt to distance Scotland from such radicalism. Here, Ranald MacDonald, the Sheriff of Stirling, was presented as a clan chieftain. Unemployed weavers were put to work constructing the ‘Radical Road’ around Salisbury Crags in Holyrood Park, Edinburgh.

But things did change after 1820. In 1832 Peter Mackenzie, campaigning to have the radicals of 1820 pardoned, published a book that detailed how the insurrection had been initiated by government spies and agents provocateurs. The authorities brought a liable case against the book and lost. This forced the government on 10 August 1835 to issues an absolute pardon to all 1820 insurgents.

In terms of political reform, the 1832 Reform Act did see an extension of the franchise. However, the addition of 60,000 voters in Scotland still left about 400,000 adult men without the vote and all women. The fight continued with the Chartist’s agitation for further extension of the franchise, in the 1830s and 40s. The Suffragette’s fight for the right for vote for women was eventually won in 1918, almost 100 years after 1820.

Interested in more stories from Stirling Castle?

Did you know that an African drummer worked at the court of James IV? Or are you looking for some ghoulish ghost stories from Stirling Castle?

There are many fascinating tales on our blog. Sign up to our newsletter to get new stories straight to your inbox!