Just over 400 years ago, on 30 August 1594, Stirling Castle hosted a magnificent royal pageant to celebrate the baptism of Prince Henry.

Born earlier that year, on 19 February, he was the first child and heir of King James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) and Queen Anne of Denmark (or Anna in Danish).

Portraits of James VI & I and Anne of Denmark in the Mary Room at Edinburgh Castle.

The celebrations involved a riveting tournament, a stately baptism ceremony and a triumphal banquet in the Great Hall. Ambassadors from England and across Scandinavia joined this celebration of the security of the Scottish royal line.

This was the first Scottish court festival to have an official published account. The choreographer of the pageants, the poet William Fowler, documented the events in detail in “A True Reportarie of the Most Triumphant, and Royal Accomplishment of the Baptisme of … Prince, Frederik Henry”.

And thanks to Fowler’s efforts, we can still share the story of this colourful event today.

Portrait of Prince Henry, aged 2, dated 1596, Dalmeny House.

An Opening Tournament

On the first day of the festivities, the King and his noblemen took part in a grand tournament. Dressed as Knights of Malta (a Catholic chivalric order), with the ‘white overthwart croce (cross), the badge of the Knights of the Holie Spirit’, they fought against other teams dressed as ‘Turks’ and ‘Amazons’. But these contests were more like a theatrical play than true combat.

In national tournaments, competitors painted different designs across their shields. These impresa showcased novelty, creativity and individuality. The King’s shield displayed ‘a Lyons heade with open eyes’.

The red lion was the heraldic symbol of James’ family, the Stuarts. The Stuarts had held the throne since 1371 and the lion represented the long history of the family’s power in Scotland.

James’ shield was a reminder of exactly who was in charge amongst all of these noble warriors. But in the end, it was James’ cousin and close advisor Ludovic Stuart, Second Duke of Lennox who won the tournament. His prize was a splendid, jewelled ring from the Queen.

The Repatorie proudly proclaims that the first day’s entertainment received ‘great contentment to the beholders’. Although, not all felt that way. The staunch Presbyterian minister David Calderwood later commented that the Catholic guises were ‘muche mislyked by good men’.

With the excitement of the tournament setting the tone, the celebrations moved to the heart of the event: the baptism ceremony.

A Classical Chapel

The baptism took place in the newly constructed Chapel Royal. As the previous chapel was now ‘ruinous, and too little’ it was decided it would be replaced. The new chapel should be ‘more large, long and glorious, to entertaine the great number of strangers expected.’.

King Charles I carried out renovations to the chapel in the 1620s. And in the 1990s, Historic Environment Scotland restored the building to its original design as far as was possible to reconstruct.

The main doorway of the Chapel Royal, which is still used, is framed by pairs of columns. They form a triumphal arch. An inscription over this archway, now gone, announced to those who entered that, ‘106 kings have left this to us, unconquered’.

Perhaps this was to warn the European ambassadors who attended the baptism of Scotland’s ability to defend itself against any external threats. But the irony is that the true reason for the downfall of many of these kings were internal struggles!

Inside the chapel, the walls are coloured with a simple wash of golden-yellow paint. Rich decorations are painted across the top. They show symbols of the house of Stuart, including the lion, rich bushels of fruit. And you can also see curiously empty roundels. They possibly originally contained portraits. Some are framed by rays of light and others by scrolls and ropes.

One of the recurring symbols is the Honours of Scotland: the sword, sceptre and the crown. These relics remain on display at Edinburgh Castle.

On the chapel’s walls, you can see the Honours of Scotland symbol flanked by a cypher. It was previously thought that ‘I’ overlaid onto a ‘6’ were Charles I’s initials (‘I’ and ‘C’). But we now know that this is more likely a six with the ‘I’ for Iacobus (Latin for ‘James’).

A Young Hercules

When it was time for the Prince’s christening everybody gathered in the chapel. The King and visiting ambassadors took their seats in a lofty pulpit in the middle of the space.

The stunning architecture was further embellished with luxurious furnishings and the walls were ‘richelie hung, with costly tapestries’. Furthermore, ‘fine velvet’, one of the most decadent fabrics of this age, decorated the ambassadors’ seats in an array of flashy colours. The coats of arms of their Princes above their respective chairs signaled their identity.

Before Henry’s grand entrance to the chapel, he was presented as a young hero. His bed of estate was laid with golden tapestries recounting the triumphs of Hercules. The legendary figure was famous for his strength and heroism. The young prince was swaddled in a rich robe of purple velvet and pearls. He was carried into the chapel under a crimson velvet canopy fringed with gold. They were the colors of the House of Stuart, of which he was the newest member.

The crowd performed psalms, sermons and hymns. But the final act of the crowning Prince Henry with a beautiful dainty crown richly set with ‘Diamonds, Saphires, Rubies, and Emerauldes’ was carried out by the father and King.

From the chapel’s open window trumpets sounded. And the Prince was proclaimed as ‘Henry Frederick’ to the people of Stirling.

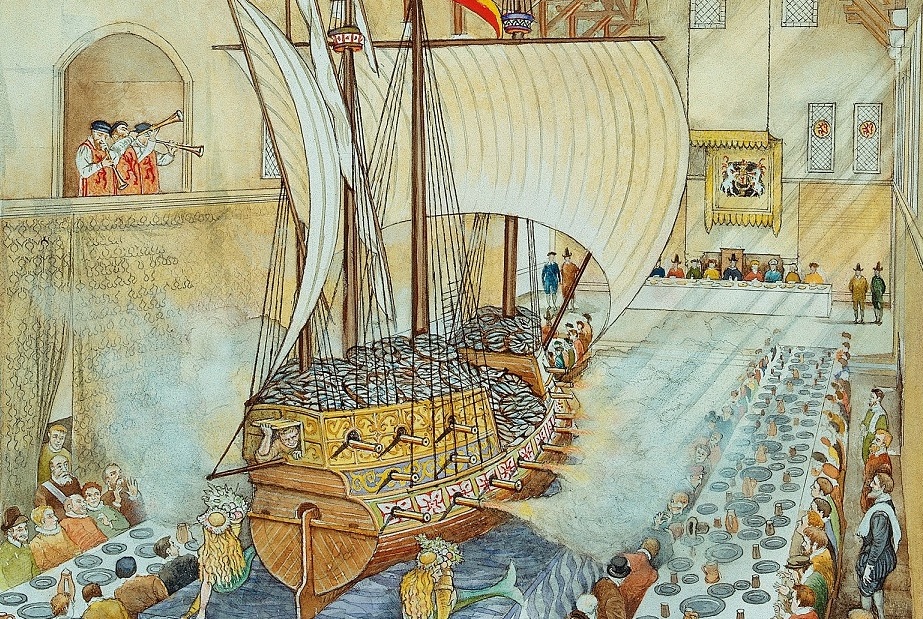

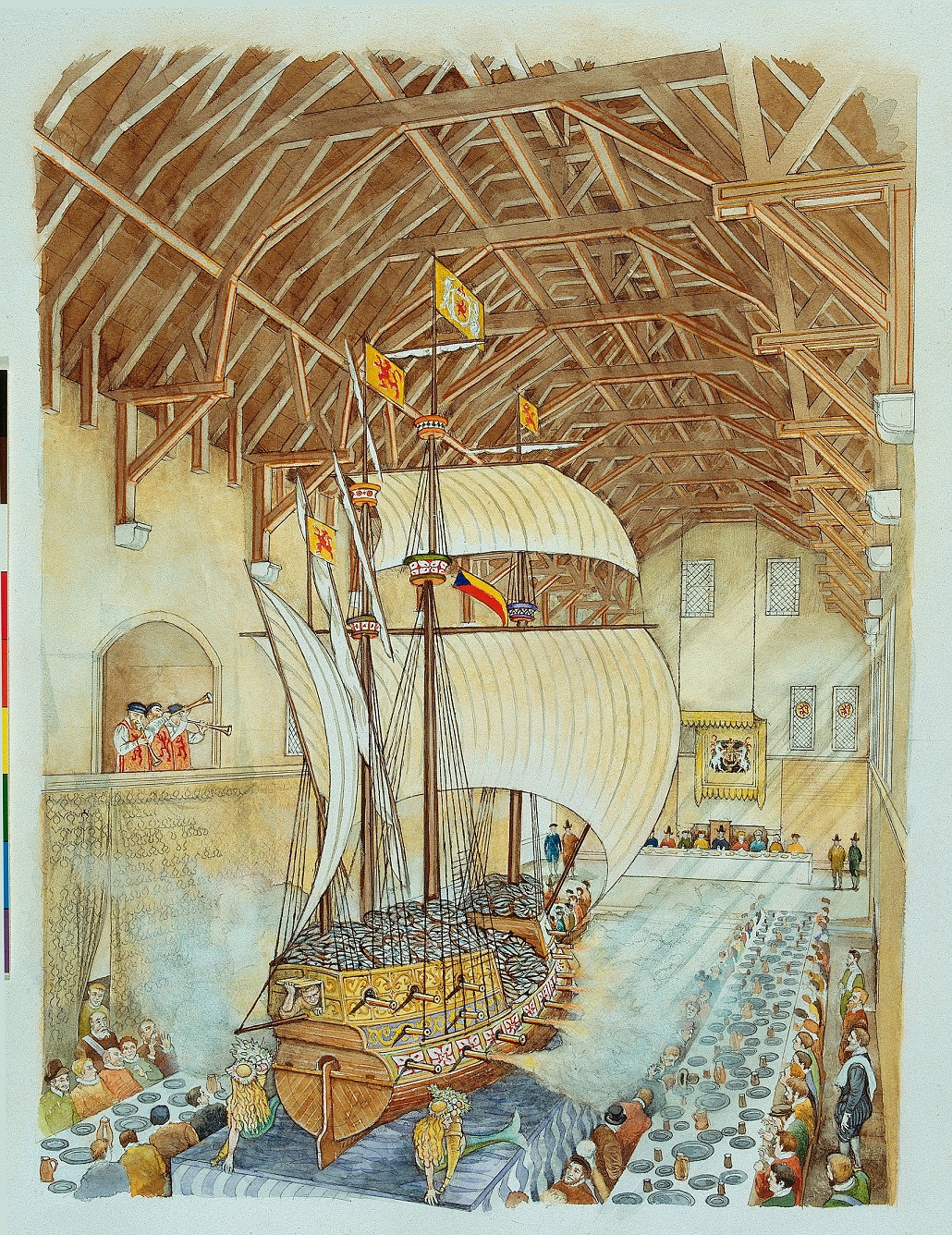

© HES, illustrator, David Lawrence.

A Glorious Banquet

After the ceremony, Henry was returned to his chamber so that the adults could commence in merriments. Up next was the grand finale. A superb banquet with a show in the Castle’s Great Hall, next to the chapel.

The royal couple and the ambassadors sat at tables in a U-shape. The remaining guests sat at two long tables along the east and west sides of the Hall. The centre of the room remained open for the performance. Everyone was therefore in view of each other, making them all part of the show.

A Lion at the Table?

The first course was carried into the Hall on a great ‘triumphall Chariot’. This vehicle must have been sizable, as it carried a table with food and several performers!

Originally the chariot was meant to be pulled by a real lion! But anxious that either the animal or spectators might become frightened, this was cancelled. It had long been popular at European royal courts to have a menagerie with a host of exotic animals on display. And King James IV had built one at Holyrood Palace, as well as a lion house. So it would have been an impressive image, if a lion had been part of the show.

Instead, the chariot was guided in by a ‘Moor’, supported by a concealed mechanical device. The image of the ‘Moor’, whether an actual individual with dark skin or a white actor in blackface, was an articulation of colonial domination in European court presentations.

The unnamed ‘Moor’ at the banquet ‘was very richly attyred, his traces were great chaines of pure gold.’ Although richly attired, the performer was still very clearly enchained.

Upon the chariot was a table bearing ‘all sortes of exquisite delicates and dainties, of patisserie, frutages, and confections.’ Around this, six ‘Gallant dames’ posed in a silent tableau. Each actress personified a different classical virtue.

Three of the ladies wore costumes of silver satin. The other trio wore crimson. Pure gold and silver thread enriched their costumes. And a crown or garland on their hair for the final touches. Feathers, pearls and other glittering jewels accentuated the spectacular ensemble.

Springing to life they recited verse in praise of the King before serving the treats.

A Most Sumptuous Ship

Following the departure of the chariot, the show’s striking centrepiece was revealed. Into the Hall billowed a ‘most sumpteous, artificial … ship’ model. It was eighteen feet long and towered over the onlookers.

On board were actors cast as the great gods Neptune, Thetis and Triton, Musicians and singing sirens supported them.

During the banquet, Neptune narrated a performance of James’ eventful expedition in 1589 to retrieve his bride. She was stranded in Norway after storms had disrupted her departure to Scotland. Neptune’s version of the tale included conspiracies of witches and fearsome foes such as ‘devillish Dragons’.

Throughout, the cast of characters aboard praised the King as a powerful and heroic leader. A commentator later noted that ‘The strangers mervelled greatlie at the shippe.’ The intention to impress the attendees through an elaborate spectacle would appear to have worked.

The ship was painted throughout with the Stuart colours and adorned with ‘the riches of the seas’, including ‘very rare and excellent’ shells, coral and pearls.

Additionally, the royal arms of Scotland and Denmark decorated the main sail. Beneath was a Latin motto praising Henry as a blessing to both of his parents’ nations.

Upon the ship was a towering gilt crystal glass holding a range of seafood delicacies including oysters, herrings, clams and crabs. And alongside this were scores of sugar fancies, a highly costly delicacy, in a variety of shapes.

A musical performance led by an actor dressed as Arion plucking his harp accompanied the dinner. In the song, Scotland, supposedly once shrouded in darkness, had now been brought into the light by James’ monarchy and family.

A Triumph

Overall, ‘everything passed off to the evening with cheerfulness’ as the guests were ‘royally feasted, nothing lacking that was required to such a triumph.’ The Prince’s baptism had been a success! Although, it had not quite been smooth sailing.

Behind the scenes, there had been a scandal. The narrator, Neptune, had meant to be wearing cloth-of-gold to single him out. However, his garments were unexpectedly stolen and donned by the ship’s pilot, afraid that he would go unnoticed by the crowd! But luckily for the King, none of his audience members caught wind of anything untoward.

The following weeks were spent in Edinburgh enjoying banquets, general jovialities and hunting before the ambassadors were ready to depart.

About the Author

Charlie Spragg is a doctoral researcher at the University of Edinburgh, holding a scholarship from the Edinburgh College of Art. Her PhD thesis explores King James VI & I’s relationship with visual and material media. Alongside this, Charlie works as a freelance advisor, including for Historic Environment Scotland on their new guidebook for Stirling Castle. She is currently working on a variety of projects for the 400-year anniversary of King James’ death in 2025.

Discover more!

There’s more stories like this in our Stirling Castle guidebook, compiled by the brilliant HES Interpretation Team.

It’s packed with all the latest research, previously unseen illustrations and terrific tales from the famous stronghold. So be sure to pick one up on your next visit!