If you’ve ever been to Edinburgh, you’ll be familiar with the hulking great “lion” of Arthur’s Seat, poised majestically above Scotland’s capital at the centre of the rugged landscape of Holyrood Park.

You’ll likely have seen Holyrood Abbey and Palace, admired the ruins of St Anthony’s Chapel and peered into the darkness to glimpse St Margaret’s Well. And if you have a taste for the mysterious or macabre, you’ll almost certainly know about the miniature coffins and tiny carved wooden corpses discovered on Arthur’s Seat in 1836.

A climb to the summit of Arthur’s Seat offers panoramic views across the city.

But there’s so much more to know about Holyrood Park! With a history of human use that stretches back at least 7,000 years, this unique landscape has countless stories to tell. And the further back we go, the more we rely on archaeologists to tell us about the people who ventured there before us.

You can see this landmark for miles around, so it’s not surprising that people have been drawn to it for millennia. It has seen farming and fort building, hunting and worship, army encampments and royal pageantry, warfare and ritual, and mystery.

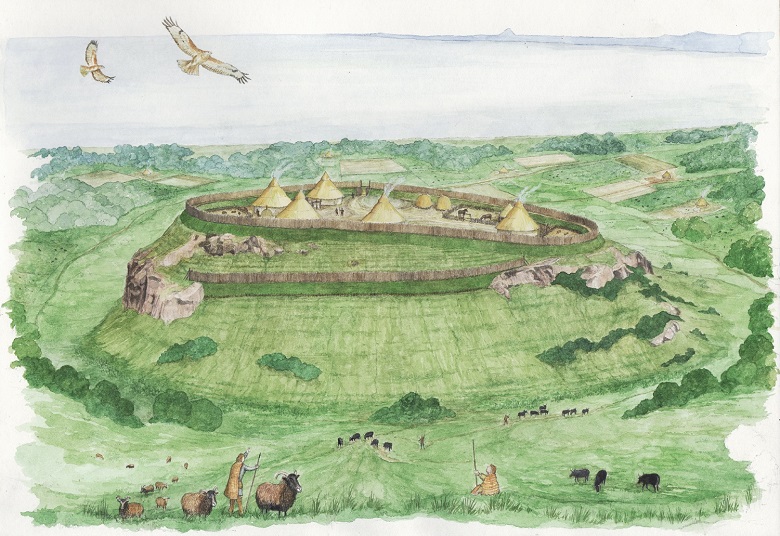

Humans have used Holyrood Park for thousands of years – this reconstruction imagines Iron Age life at Dunsapie Fort

A special place

The word “unique” is often overused, but Holyrood Park is a truly special and significant archaeological resource. It is highly unusual for cities to encompass a landscape like this which has been used for thousands of years and which has not been built over.

There are over 111 known archaeological sites within Holyrood Park, though many are poorly understood. The whole park is designated as a Scheduled Monument, highlighting its importance as an archaeological landscape.

Along with 111 archaeological sites, rare plant species have been recorded in the park.

The extensive nature of the park, its time-depth in terms of human presence and the many discoveries, suggest that important archaeological remains could exist anywhere across much of the park.

Let’s explore how archaeology has helped us to learn more about Holyrood Park’s hidden past.

Burials in the park

The aspect of archaeology that people probably find most fascinating is the discovery of human remains. Perhaps because we are fascinated by our own mortality?

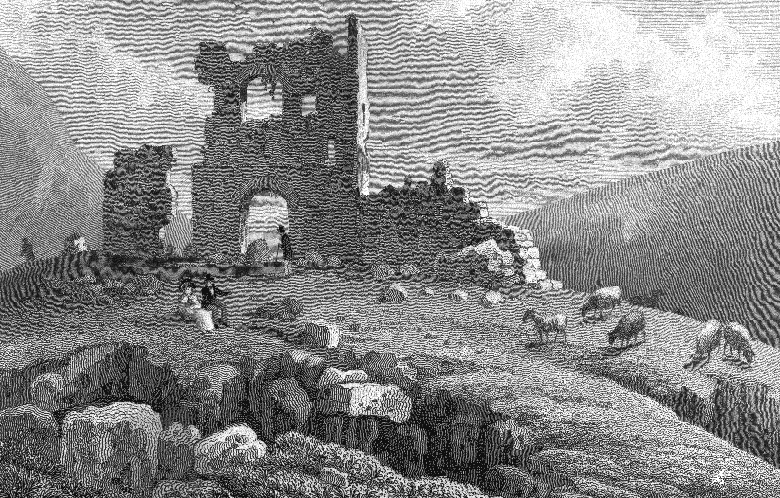

We know that there was once a burial ground beside St Anthony’s Chapel. In the early 1940s, while repairs were being made at the chapel, workers discovered several burials in the narrow strip of ground on the north side of the building. These were less than a foot below the surface, and they were probably casual interments seeing that the graves were not lined in any way. Beside them was unearthed a small potsherd of 16th or 17th century date.

An engraving of St Anthony’s Chapel from ‘Modern Athens’ by TH Shepherd, published in 1829. (© HES, via Canmore)

In 1859, while digging a new road from Edinburgh to Duddingston through an area named Windy Gowl, several underground cavities were unearthed. One contained an urn and was probably Bronze Age in date, a further seven were found containing human remains of unknown date.

A small axehead and some copper coins were also discovered. The nearby crag has been known as ‘Hangman’s Knowe’ – could these shallow graves be related to a historic execution site?

The urn discovered at Windy Gowl (© National Museums Scotland)

The Duddingston Hoard

The Duddingston Hoard is a fascinating collection of Late Bronze Age artefacts discovered in 1778 at Duddingston Loch. Workers dredging the loch unearthed a variety of bronze objects, including swords, spearheads, and a bucket handle, along with human bones and animal horns.

The hoard dates back to around 1000-800 BC and includes about 29 damaged or broken swords and blades, 28 broken spearheads, and other items. Many of these objects were deliberately bent, broken, or burnt, leading archaeologists to believe they might have been part of ritual deposition or offerings to the gods, spoils of warfare or deliberate decommissioning.

Duddingston Loch

The Duddingston Hoard is also important because it is the first entry registered on the list of items taken into care by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, which was founded in 1780.

The artefacts are now housed in the National Museums Scotland. Head to the National Museums Scotland blog for more fascinating insights on the hoard by Matthew Knight, their senior curator of prehistory.

The Duddingston Hoard (© National Museums Scotland)

Hill forts

A good way to feel safe, secure and powerful is to build yourself a fortress somewhere high. Being on a hill gives you a better view of attackers approaching from a distance, and allows you to prepare. It’s also a good way to assert your dominance, because you can be seen from miles around.

The hills and cliffs of Holyrood Park are a great location to build a fort, so it’s no surprise that we know of four different hillforts scattered around the area. Hillforts were surrounded by ditches, wooden walls or palisades, and mounds of stone and earth (ramparts) to make it harder for enemies to attack. They may have been enclosures for animals.

Dunsapie Craig, the site of an Iron Age hill fort, an excellent spot to appreciate Holyrood Park’s archaeology.

The biggest and the “best”

The largest, and possibly the earliest hillfort in the Park is the one located on Salisbury Crags. Dating from around 500 to 100 BC, it may have contained houses and other structures. However, not much in the way of archaeology seems to have survived inside the enclosure. This has led archaeologists to suggest it may have been used seasonally, with temporary structures inside its walls. Another theory is that it was an enclosure for livestock.

The fort at Dunsapie Craig is smaller but more elaborate. Here, the hilltop was surrounded by ramparts built from earth and stone. Inside, there are traces of circular platforms where timber roundhouses probably stood. In 1996, three bronze axe heads were found by an illegal metal detectorist (check out our latest guidance for detectorists). Archaeologists from the National Museums Scotland excavated the site. The axe heads were in poor condition, but if you look very closely, traces of decoration are just about visible.

The axe heads discovered at Dunsapie Craig (© National Museums Scotland)

Farming in the park

Today, one of the most visible clues to past life in Holyrood Park is its cultivation terraces. You might have noticed them cut into the hillside near Dunsapie Loch. They look a bit like steps for giants!

Other agricultural features include the ‘rig-and-furrow’ fields, which look incredible from above! Rig-and-furrow is a technique of ploughing that creates ridges and furrows in the land. It’s an example of how land was worked since medieval times.

Traces of ancient farming can be seen in this aerial photo of Holyrood Park.

The plough was moved across the field in one direction, then turned around and moved back again. This process was repeated each year on the same strip of land, building up ridges and furrows. There are great surviving examples visible on Prestonfield Golf Course.

Ridges and furrows on a golf course beside Holyrood Park

There were probably people farming here at least as far back as the Bronze Age. Agricultural activity continued throughout the medieval period and beyond. The park was also used for grazing animals. It’s no coincidence that you’ll find the Sheep Heid Inn in Duddingston Village!

Locals over a certain age may remember a time when thousands of sheep still grazed the park. However, the sheep were moved out of the park in 1977 for their own safety. Now and again though you might spot some heritage breed visitors to the park thanks to the Scottish Wildlife Trust. Our bovine visitors help to regenerate areas of land and provide some natural fertilisation for the plants!

Shetland Cattle grazing in Murder Acre

Holyrood Park’s Archaeology today

In recent years, we’ve been glad to welcome archaeology students to the park as part of a Field School. These investigations are a collaboration between the University of Edinburgh and AOC Archaeology, with grant funding and other in kind support from us.

These sessions provide valuable practical skills and training to the next generation of archaeologists. It helps to enhance our understanding of the Park’s archaeology and the significance of what remains.

This season’s work focused on:

- a later prehistoric settlement on the slopes of Dunsapie Hill

- probable structural remains on the lower slopes of Crow Hill

- and the Iron Age hillfort on Samson’s Ribs.

At Dunsapie, this year’s excavations revealed the entrance into the settlement and a beautifully preserved cobbled floor surface.

Over on Samson’s Ribs – another of the four hillforts within the Park – students uncovered an Iron Age roundhouse, set immediately inside the fort’s stone rampart. The soil on this hillfort is very thin leaving these significant archaeological remains at risk of erosion. The more we understand these remains, and the better record we have of them, the better we can protect them and avoid losing valuable archaeological evidence.

The trench on Crow Hill was the most surprising. Possible structures have been identified by various surveys in the past, but the character and date of these has often been debated and remained uncertain. What was assumed to be a medieval or later farmstead turned out to be a probable prehistoric roundhouse, a substantiation structure that was completely unknown to us – and likely over 1000 years older than we had previously thought.

To find out more about what the students discovered, head to their blog.

See Holyrood Park’s archaeology for yourself!

Holyrood Park’s archaeology, geology history and wildlife make it a place of extraordinary significance and fragility, to be cherished and conserved for future generations.

Our Strategic Plan for Holyrood Park sets out a framework to address key challenges and maximise opportunities for the Park.

For expert insight into this special site, join our Rangers on an “Arthur’s Secrets” guided walk. Additionally, you can continue your exploration on the blog with a Women’s History tour of Holyrood Park.