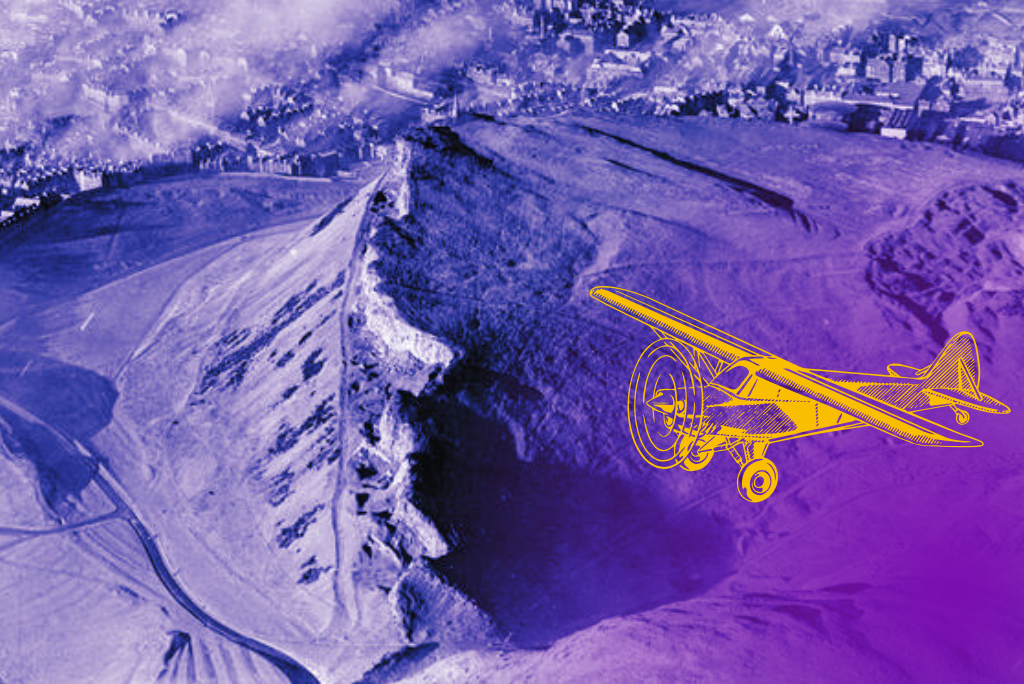

Taken 75 years ago, on 20 November 1949, this photo gives us an amazing glimpse into the history of Holyrood Park. Can it tell us about the park’s future too?

To really appreciate the photo, you have to make use of the zoom feature on Canmore, diving ever deeper into the historic streets of Edinburgh. Much of it is covered in a blanket of low cloud and smoke, as residents fend off the cold November day with their coal fires. A reminder of why Edinburgh was once known as “Auld Reekie”.

An aerial view of Holyrood Park taken in November 1949. © Courtesy of HES (Aero Pictorial Collection). Zoom in on Canmore.

But dominating the middle of the photo is Holyrood Park. At first glance, it looks very similar to the park we know and love today. But on closer inspection it’s a fascinating game of “spot the difference”. Some of the differences tell a story of positive progress. Others provide a warning about climate change and increased footfall.

Take a closer look at the park today on Google Maps. Image © Google.

Who took the photo?

The photo was taken by a company called Aero Pictorial. The small company was founded in 1934 by Cyril Murrell and was based in offices in Regent Street in London. Cyril was more-or-less a one-man band for this company. He was a pilot and photographer and this company brought his passions together. It’s highly likely that Cyril himself took this photograph.

Cyril typically took photographs of England and Wales, so this view of Edinburgh is quite unusual for his catalogue. You can see more of Cyril’s photos of Scotland on Canmore.

This impressive shot of Culzean Castle is another of Cyril’s images. This was taken in 1953. © Courtesy of HES (Aero Pictorial Collection)

After Cyril died in 1958, Aero Pictorial was merged with the larger company Aerofilms. It is very likely this amazing photo ended up in our collections in 2007 when the Aerofilms archive was acquired for national archives across the UK with support of the Heritage Lottery Fund.

If you’d like to pop in to view the original negative in our archive you can find out how to arrange a visit.

Spot the difference

At first glance, it might look like not much has changed but go back and take another look!

Perhaps the most striking thing is how different the landscape looks in comparison to what we see today.

More trees

In the 1949 photo you can see that the area that backs on to St Leonards and the Pleasance is almost entirely without trees. This is now an area of woodland, thanks to an extensive tree planting scheme which took place after the 1993 management plan championed the addition of trees. The trees were planted primarily to screen the city from the park and help to keep the park feeling like a wild place in the centre of the city.

This photo was taken in 2010 and shows the small areas of woodland growing around the perimeter of the park, which was previously grassland. Take a closer look on Canmore.

The trees offer a bit of variety in terms of habitat. But you might be surprised to hear that too many trees can actually have a negative impact on the park. They can threaten the park’s archaeology, geology and grasslands, which are the largest and most diverse lowland unimproved grasslands within the Lothian area.

A ewe-nique landscape

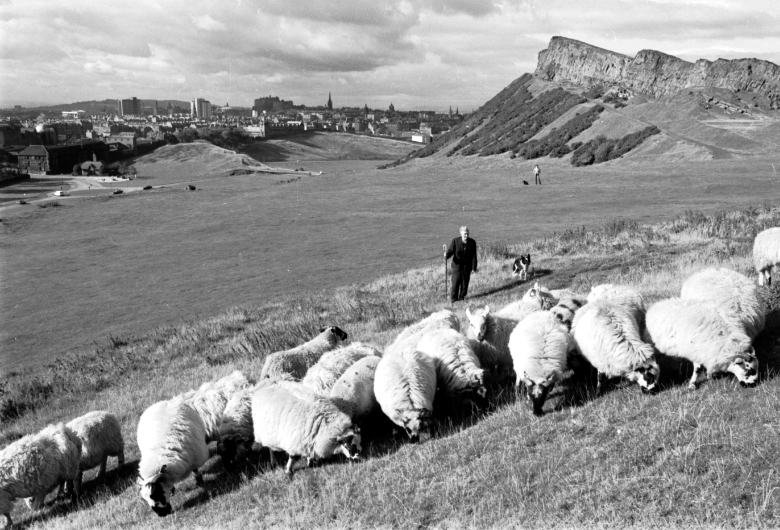

Did you know that up until the 1970s sheep used to graze the land? As they munched their way around the park they stopped trees, bushes and gorse from growing. This might sound bad, but the sheep actually helped to give the park some of its special characteristics. For example, gorse cover has grown by 133% since grazing stopped in 1977. Gorse can cause various issues in the park, including exacerbating wildfire, threatening archaeology and encroaching on the species rich grasslands.

‘City shepherd’ Eddie Sutherland with his sheepdog Nap in Holyrood Park in November 1977. © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Could you see sheep back in the park any time soon? Never say never! But there would be lots of factors to think through. This would include making sure they were safe within the park.

Turf wars

One of the most valuable environments we have in Holyrood Park is the grassland. Grasslands are rich with many different species. But sadly grassland is amongst the most threatened habitats in Britain. It’s also a landscape that is proving difficult for us to maintain in the park, thanks to erosion and encroaching tress, gorse and scrub.

These wild, grassy areas of Holyrood Park are important homes to a lot of creatures. For example, ground nesting birds such as skylarks and short-eared owls live here.

Recognising the importance of this environment and working to improve it has had its success stories. For example, the northern brown argus butterfly became extinct in Holyrood Park in 1869. But thanks to improving habitat, it re-appeared in the park in 2005 and the population has continued to increase annually. Rock-rose, which grows in the park, is the food plant for the larvae of this species.

The northern brown argus butterfly (left). Rock rose, which supports the larvae of the butterfly.

Since the 1980s, Holyrood Park has been recognised as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). In 1985 the area around Duddingston Loch was awarded SSSI status, and in 1986, the Arthur’s Seat area of the park followed suit. Nature Scot monitors the SSSI status of the park and flags up areas where we’re doing well and also highlights areas of concern.

The threats to grassland habitat is something we’re already acting on and is addressed in our landscape management plan for the park.

The Innocent Railway

In the bottom left of the photo, you can see the Innocent Railway. It was still in operation when this photo was taken. The Railway brought coal into Edinburgh from the coal pits of Midlothian, fuelling many of those chimneys we can see in the photo! The Innocent Railway closed 19 years later, in 1968.

This archive photo taken between 1880 and 1900 shows the Innocent Railway exiting the southern end of the St Leonard’s Bank Tunnel with King’s Park and the rock formation known as Samson’s Ribs, to the left © Courtesy of HES (Whytock and Reid Collection).

In the 1980s part of the Innocent Railway from St. Leonards to Brunstane was re-opened as a cycle path and is part of the National Cycle Network Route 1. Find out more about the history of the Innocent Railway elsewhere on our blog.

Erosion

Back in the 1940s and 1950s the park wasn’t frequented by as many visitors as it is now. Growing numbers of locals using it for recreation and tourists visiting, combined with the effects of climate change, have caused serious erosion and an increased number of footpaths around the park.

We don’t have exact figures for visits to the park, we estimate that it is now in the many millions per year. In 1950, Edinburgh’s population was 453,000. Today, it has grown to 540,000—a 19% increase. Back in 1949, the Edinburgh Festival was only two years old. It’s now a major event, attracting about 3 million visitors annually. In Edinburgh, year-round tourism is estimated to contribute over £1.8 billion to the city’s economy. And many of these residents and visitors will find themselves in Holyrood Park every year.

This aerial image of the Crags was taken in 1973. The lines of the footpaths are quite different to how they appear today. Google Maps (below) shows much more pronounced paths criss-crossing the landscape – especially at the edge of the Crags. © RCAHMS. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

While we love that the park is a great resource for people – providing a place that improves our physical and mental heath and is a must-visit attraction in Edinburgh – we need to make sure we’re protecting this truly unique asset in the heart of Scotland capital city. The wildlife, geology and history of the park is depending on us to protect it and make the park a sustainable place now and in the future. You can take a look at our plans to achieve this in our Strategic Plan for Holyrood Park.

The rifle range

Did you know that the Hunter’s Bog area of Holyrood Park was used as a rifle range from at least the 1830s until the 1950s?

The area was first used for target practice by the Edinburgh Castle garrison. During the late 1880s it was used by the volunteer brigades of the Royal Scots. The range continued in operation until at least 1953, when it was still serving the Territorial Army (TA). Some older residents of Edinburgh might remember the days when red flags flying at Hunter’s Bog meant it was a no-go area for walkers!

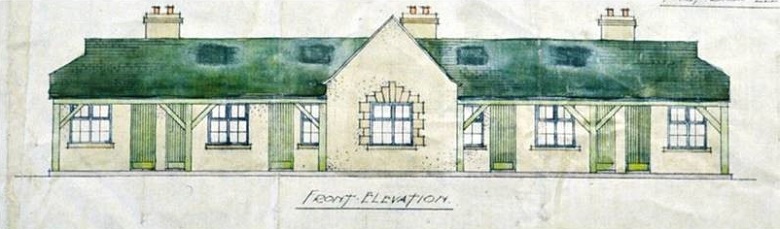

An architect’s plan of the old volunteer’s hut in Hunter’s Bog, which can be seen in the aerial photo. © Crown Copyright: HES

Our photo from 1949 show the old volunteer’s shelter hut, which was constructed around 1914 and would still have been in use by the TA at this time. The buildings in Hunter’s Bog were dismantled in the 1950s, shortly after the rifle range was decommissioned.

The future of the park

Holyrood Park is a truly unique landscape in the heart of Edinburgh. A fascinating and dramatic melding of geology, plant habitats, history, and cultural influences, it is the largest and most challenging site in our care.

A handsome pheasant in Holyrood Park.

Our Strategic Plan for the park sets out a vision and objectives to guide the Park’s development over the next decade, focusing on climate action, biodiversity protection, and visitor wellbeing. Download the plan now for a glimpse at what the park might look like in 2035.

Aerial photography in the park

We looked into recreating this image with a drone, but unfortunately the altitude of this image captured from a plane is much higher than we can fly a drone. By our estimates, Cyril took this image from an altitude of around 580 metres. In the UK, the maximum height you can legally fly a drone is 120 meters.

If you’re thinking of flying a drone at Holyrood Park, did you know that you need to get permission first? Find out more about drone flying at our sites.