How did the Battle of Culloden start, and why was it so important? Uncover the events before and after with help from our Inventory of Historic Battlefields.

1. What was the Battle of Culloden?

The Battle of Culloden was the last of the Jacobite Risings; a series of armed uprisings against the House of Hanover over the course of almost 60 years, that aimed to restore the Stuart monarchy to the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland.

It was the last ‘pitched’ battle fought on the British mainland – this means one where the time and place were determined beforehand. Its aftermath would have widespread impacts both within Scotland and further afield.

When was it?

The battle took place on Drummossie Moor (which today is about a half hour bus ride from Inverness) on 16 April 1746. It marked the end of an eight-month campaign by Jacobite forces in Scotland and England.

Who was fighting?

The battle was fought between Hanoverian Government forces led by Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, and Jacobite forces led by Charles Edward Stuart.

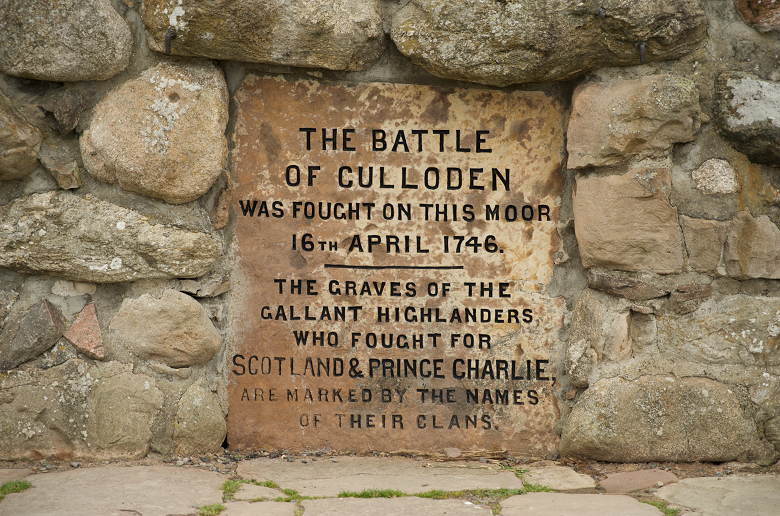

The 19th century memorial cairn at Culloden Battlefield.

2. What were they fighting about?

In the simplest terms, the two sides disagreed over religion and succession. One side thought the Protestant Hanoverian line should be in charge. The other thought the Catholic Stuarts had a better claim.

But the run up to this battle was long – the Jacobite uprisings spanned a period of fifty-seven years. And there were other conflicts playing out across Europe during this period too, some of which involved figures who were on the field at Culloden.

James VII and II and some of his family had gone into exile in 1688 after he was ousted in favour his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange. The exiled king and his supporters waged war against the new regime across the British Isles in an attempt to restore James to the throne, but were unsuccessful.

Under the reign of William and his wife Mary, the English Parliament passed a law called the Act of Settlement in 1701. This ‘act for the further limitation of the crown’ was designed to ensure only Protestants were eligible for the throne. James Francis Edward Stuart was a Catholic.

When the exiled King James VII died in 1701, his son James Francis Edward Stuart (nicknamed ‘the Old Pretender’) took up the cause to restore his line. His attempts were also unsuccessful, but demonstrated that there remained significant support for ‘The King Across the Water’.

The cause was then taken up by James VII’s grandson Charles Edward Stuart – also known as ‘the Young Pretender’ or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’.

Portrait of the Young Pretender (Bonnie Prince Charlie) in the Mary Room at Edinburgh Castle.

3. How did the Battle of Culloden start?

Bonnie Prince Charlie landed at Glenfinnan on 19 August 1745, and swiftly gathered an army of his supporters in the Highlands.

The Jacobites initially met with some success. They entered Edinburgh without resistance and went on to fight Government forces at the Battle of Prestonpans on 21 September. By December they had made it to Derby (in the middle of England), but by this point the campaign was beginning to unravel.

The Jacobites retreated to Scotland and, despite continued attempts to gain the upper hand (including another victory at the Battle of Falkirk Muir on 17 January 1746), they gradually withdrew back into the Highlands.

Their last stand took place at Drummossie Moor on 16 April 1746.

Culloden House served as Bonnie Prince Charlie’s headquarters and accommodation before the Battle of Culloden. The house that stands there today was built some 40 years after the events of Culloden. An account of the earlier house describes it as a “‘plain four-storied edifice, with battlemented front and central bell-turret'”.

The Culloden House which stands here today was built in the 1780s, after the battle. Explore more images and records on trove.scot.

Although the Jacobites picked the site of the battle, in a location which blocked the approach to Inverness to the west, it was the Government army which set the scale of the field, coming to a halt around 700 m to the east of the Jacobite line. This helped them maximise both the use of their artillery and the distance over which the Jacobites would have to charge.

4. Who Won the Battle of Culloden?

The battle opened with an exchange of artillery fire, and Government guns quickly took the upper hand.

Eventually the Jacobite infantry surged forward, beginning with the centre of the line made up from the men of Clan Chattan.

However, a combination of boggy ground, a track running across the moor, gently sloping topography and heavy fire further all worked to compress the Jacobite centre and right toward the left flank of the Government line.

The MacDonalds and others on the Jacobite left were the last to move forward, starting even further from the Government line. Before they could reach the Government line, heavy fire effectively stopped them in their tracks.

A mural of the Battle of Culloden at Fort George.

Meanwhile, as the Jacobite centre and right approached the Government lines, the Hanoverian troops fired a volley of musket fire, along with canister shot from their artillery, directly into the clustered Jacobite force.

The losses must have been terrible, but the momentum and determination of the charge was enough to carry the attackers crashing into the front of the Government left, between Barrell’s and Monro’s regiments.

Although they managed to hack their way into the front line, many Jacobites found themselves sandwiched between the muskets and bayonets of the front and second lines. It is here that the Jacobite struggle effectively came to a bloody end.

Meanwhile, the dragoons on the Government left, under General Hawley, moved behind the Jacobite right, after passing through breaches made by the Campbells in the enclosure walls to the south of the field. By this time, all was lost for the Jacobites.

Under the protection of a covering action by their cavalry and the infantry detachments of the second line, Charles’ army streamed from the field.

What Happened Next?

Having won the battle, the Government line advanced in close order, brutally dispatching the wounded and those too slow to escape.

The cruel aftermath of the battle has entered the popular imagination and there are many stories of Jacobite wounded being dragged from their places of shelter and shot against walls, and of the barns in which they sheltered being burned to the ground after the doors had been bolted.

Some survivors did regroup at Ruthven Barracks to await word from their leader, Bonnie Prince Charlie. His message arrived on April 20, reading ‘Let every man seek his own safety in the best way he can’.

Ruthven Barracks

Famously Charles himself was able to escape first to the West Coast, then ‘over the sea to Skye’ with the help of Flora MacDonald. He eventually made it back to the continent, and would never return to Britain again.

Meanwhile the Duke of Cumberland, determined to end the Jacobites once and for all by crushing their very way of life, earned himself the nickname of Butcher Cumberland for his army’s brutality.

Severe measures were introduced to keep any Jacobite activities at bay, with sustained oppression of the Highlands by the Government in an attempt to break down the clan system.

Fort George

Part of the government’s measures to take control of the Highlands was the construction of Fort George. This mighty fortress on a promontory overlooking the Moray Firth was the ideal location to keep a close eye on any potential Jacobite activities and avoid capture.

The government had previously recognised the need for a strategic military presence based within the Highlands, and constructed a network of military roads, some of which survive today. They also built fortresses at Fort William, Fort Augustus and Inverness, and barracks such as Ruthven and Bernera. However, the building of Fort George following Culloden eclipsed these in scale, and was the largest construction project in the Scottish Highlands until the building of the Caledonian Canal.

It took 22 years and 1,000 men to build the stronghold. Lieutenant-General William Skinner designed Fort George, named after George II, and he became the first governor of Fort George.

He mapped out the complex layout of defences on the landward side where Jacobite assault was expected. Long stretches of rampart and smaller bastions protected the remaining seaward sides.

Today, Fort George is one of the largest and best-preserved 18th-century fortifications in the world.

The Highland Clearances

The crushing defeat of the Jacobite rebellion and measures to take control of the Highlands also paved the way for the Highland Clearances. The Clearances had a huge impact and eroded large parts of the cultural identity of the Highlanders. The clan system was dismantled, the chiefs lost their power and large parts of the customs and traditions of the Highlands were lost.

Many landowners in the Highlands were facing rising debt. With the agricultural revolution, many landowners saw a chance to make their lands more profitable through farming and forcibly evicted their tenants with little notice, many of whom had been living on these lands for years.

The end of the Napoleonic Wars would see a second wave of clearance and emigration as inflation soared, the kelp industry floundered, and potato blight hit.

The Clearances had a huge impact and eroded large parts of the cultural identity of the Highlanders. The clan system was dismantled, the chiefs lost their power and large parts of the customs and traditions of the Highlands that shaped the cultural identity were lost.

5. What was the cultural impact?

The Battle of Culloden was a defining moment in Scottish history, as well as potentially one of the most emotive battles to have been fought in the UK. It’s also the most intensively archaeologically and historically investigated battlefield in Scotland.

Art, literature and music

Mixed with the romantic imagery of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Highland Jacobites, its lasting cultural legacy is no great surprise.

In the years following the Battle to the modern day, the story and emotions surrounding Culloden are frequently explored and shared through a wealth of artistic work.

In literature, Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous novel Kidnapped was first published in 1886, which begins in the aftermath of the Battle of Culloden and explores the years following the battle through the eyes of David Balfour.

This statue on Corstorphine Road in Edinburgh, by Scottish sculptor Alexander “Sandy” Stoddart, was unveiled in 2004. It depicts Alan Breck and David Balfour, the main characters in Kidnapped.

One of the most famous portrayals includes David Morier’s An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745, which was created in the years following Culloden. This is held in the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

You can also find the story of the battle being explored in music, not just in traditional Scottish song but in a range of genres, from Handel’s oratorio Judas Maccabaeus to Argentine band Sumo’s Crua Chan.

In this song, famous and distinguished Jacobite officer, Iain Ruadh Stiùbhart (John Roy Stuart) tells the Jacobite perspective on the battle, the bloodshed and the betrayals of clan members.

And of course there’s the Skye Boat Song, a Jacobite style lament written in the 1880s to the Gaelic tune Cuachan nan Craobh, and used to teach many a Scottish school child how to play the recorder in the 1990s.

On the silver screen

In 1964, the BBC aired a film by docudrama pioneer Peter Watkins that combined historical re-enactment with documentary film making. He used local people to help stage the battle, some descended from original participants.

A couple of years later, the Doctor and his travelling friends arrived in the Scottish Highlands in 1746, as part of a 1966 Doctor Who serial. Most of ‘The Highlanders’ is sadly missing, like many other series which were deleted by the BBC for practical reasons. Some remnants do remain – but only in short clips and photographs. Well, and in the naming of Diana Gabaldon’s Jamie Fraser, inspired by the Doctor’s companion Jamie McCrimmon and the actor who played him, Frazer Hines.

Kidnapped has been adapted for the screen on a number of occasions, including as theatrical films in 1960 and 1971, a TV mini-series in 1978 and a TV movie in 2005.

More recently, the Battle of Culloden and its significance in Scottish history is emphasised in the book and TV series, Outlander. No spoilers – but the battle is a memorable and emotive moment for fans of Jamie Fraser. The series has led to much broader international awareness of the Battle of Culloden, and many Outlander tourists make the trip to visit the important site every year.

Outlander fans also make the journey to nearby Clava Cairns whilst in the area.

Visiting today

The National Trust for Scotland has owned parts of the battlefield since 1945. They have partially restored the terrain to its appearance at the time of the battle. This has included burying overhead telephone cables, removing forestry from the centre of the site, and re-routing the road that ran through the clan cemetery.

The battlefield is one of the most popular heritage tourist destinations in the Highlands. It has become almost a place of pilgrimage for ex-patriot Scots and other members of the Scottish Diaspora.

Culloden Battlefield Visitor Centre, run by the National Trust for Scotland.

Our role at Culloden

Historic battles hold a significant place in our national consciousness and play an important part in our sense of identity. These momentous events live on today, through memorials, music, poetry and literature. Here at HES, we look after The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – where most of the information in this blog came from.

Our inventory is designed to help planning authorities and other public bodies manage change. The information included can also help individuals and communities care for battlefields. By maintaining it, we hope to help protect Scottish battlefields for future generations.

Some individual features of battlefields can also be designated as scheduled monuments or listed buildings, which is the case at Culloden.

That means we’re a statutory consultee whenever the local planning authority gets an application to make changes to the area around the battlefield. We give advice to planners and Scottish ministers based on all the evidence available to us, knowing that at this site there are views which are the same today as they were back in 1746.

You can also find images of objects, archive materials and the battlefield itself on our new resource, trove.scot