There are few events in Scottish history more heartrending than the Highland Clearances. Songs have been sung about them, paintings created, poems written and plays performed. Most of you will have heard of them in one way or another. And their impact has left its mark on Scotland, even today. But what exactly happened, when, and why?

The beginning of the end

After the Jacobite Rising of 1745 ended at Culloden, an era of social, economic, and agricultural change began in the Scottish Highlands. Estates which had been forfeited by supporters of the Jacobite cause were taken over by new landowners.

Thatched croft houses at Skye Museum of Island Life. © Cairns Aitken. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Up until then, the land had been divided into small townships or baile that people inhabited and farmed. These were overseen by someone known as a ‘tacksman’ who didn’t own the land themselves, but would sublet land to the tenants while making a profit. Flora MacDonald, who helped Bonnie Prince Charlie to escape after the Battle of Culloden, was a member of the tacksman class.

A change of land ownership was seen as an opportunity to change the approach to managing the land. Although changes had begun before the Jacobite Rising, the process increased in pace after 1746 as wealthy new landowners wanted to maximise their profits.

Farms were consolidated into larger units, land was enclosed, and sheep were introduced, taking over from the more traditional stock of cattle. Rents were increased. Not only did the changes impact the landscape, but they displaced the people who lived there. All this is why, when we think of the clearances, we envision people being pushed off the land to make way for sheep.

While clearances took place on estates around Scotland, the Highland Clearances had the additional impact of devastating Gaelic-speaking communities. The combination of anti-Gaelic laws following Culloden, and then the Clearances destroying Gaelic-speaking communities, lead to a low point for Gaelic from which the language is arguably still trying to recover.

The ‘first wave’

The first batch of clearances began in the 1750s and continued until after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

Initially, most estate owners intended to redistribute the population to other parts of their lands, this tended to be coastal areas, which were not as agriculturally productive.

There were some coastal crofts, but it was almost impossible for tenants to survive on these by farming alone. Some were encouraged to take up fishing or kelp farming. Kelp farming was big business from the mid-18th century as it was an important ingredient in the production of soap and glass. By the early 19th century, kelp manufacturing employed 60,000 people in Scotland.

Kelp-burning at Kenavara on Tiree, Argyll. This photo was taken in 1903 and shows the process of kelp burning – a traditional technique, unchanged since the 18th century. Zoom in on trove.scot for a better look. © Courtesy of HES (Erskine Beveridge Collection)

However, in reality, many tenants were simply evicted with no intention of finding them a new location. In addition, those who were sent to the coast had no knowledge of this way of life, and they struggled to survive in their new situation.

The ‘second wave’

The end of the Napoleonic Wars brought economic problems and a series of disasters. Inflation soared, and the kelp industry floundered. In 1836-7 a potato blight hit the Highland region, and in 1846-8 there was a famine in the Highlands.

Crofting rents collapsed, and some unscrupulous landowners saw this as an opportunity to get rid of their less profitable small tenantry once and for all. Some landowners even burnt down crofts to force the tenants out.

All this resulted in the ‘second wave’ of clearances (1825-55), with the poorest tenants having their emigration out of the area arranged, and in some cases paid for. Although this would have been no consolation to the stricken people involved!

Where did the people go?

What happened to those who were evicted? Some did make a success of a new life on the coast or went to work on farms in the southern highlands and the lowlands.

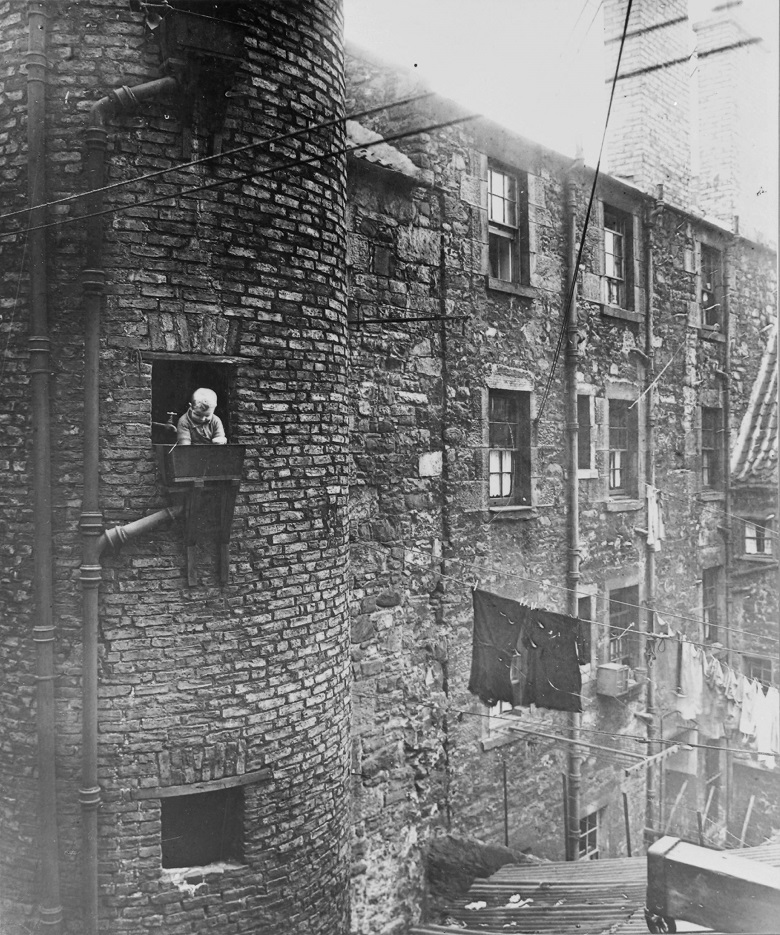

Others travelled to cities such as Glasgow and found employment in the factories there. But imagine what it must have been like, living one moment in the clean air and quiet of the Highlands, and the next working in a noisy, smelly city, surrounded by thousands of people.

This image shows the back court of a Glasgow tenement in the 1930s. Glasgow’s earliest tenements were built in the mid-19th century as a quick solution to house the growing population. Take a closer look on trove.scot. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Many Highlanders left Scotland altogether, and started a new life overseas. America, Canada and Australia were top destinations but Scots ended up all over the world. And sadly, many people starved to death or fell ill and died on the road, as they struggled to find somewhere to live and work after eviction. These Highlanders took their Gaelic with them to these countries. To this day, there are fluent Gaelic-speaking communities in Nova Scotia, and countries such as New Zealand have many Gaelic place names.

Am Ploc (Plockton) was once an an embarkation centre during the Clearances. © James Gardiner. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

A changed landscape

It’s hard to find reliable numbers for those evicted during the clearances, but estimates range between 70,000 and over 150,000 displaced people.

Remember when we think of many parts of the Highlands as a deserted wilderness today, things were not always like that. The modern Highland landscape was manufactured by wealthy estate owners in their pursuit of more money, with no regard for the people who had worked the land for them for hundreds of years before.

Fighting for change

But there was a glimmer of hope for those who remained crofters. In 1886, after many long years of poverty among remaining tenants, economic depression, and bad storms, the Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act was passed.

This came after a series of disputes and disorder, starting with the Bernera Riot in 1874 and culminated in a fierce battle, led by Skye crofting tenants, known as the Crofters’ War in 1882.

A key figure of this Land Agitation movement was Màiri Mhòr nan Òran (‘Great Mary of the Songs’, or maybe more properly ‘Great Màiri, the Songstress’).

Màiri Mhòr nan Òran. © Gaidheil Alba / National Museums of Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Renowned across Victorian Scotland and abroad, Màiri wrote many Gaelic songs now considered classics. Land agitation and Clearance was a key theme in her work. In perhaps her bestknown song, ‘Nuair Bha Mi Òg’ (‘When I Was Young’), Màiri reflected on the changes that have taken place in Skye in her lifetime, and its many empty houses. ‘Nam faicinn sluagh, agus taighean suas ann / gum fàsainn suaimhneach mar bha mi òg’ (‘If I only saw people and houses there / I’d grow joyful, like I was when I was young’).

Crofters Holdings Act

In the aftermath of the Crofters’ War a commission was set up to look into the conditions the crofters were experiencing. This scrutiny did raise awareness of the terrible exploitation that the crofters were exposed to. While the recommendations of the commission were not enshrined in the Crofters Holdings Act, it did pave the way.

The Act gave the remaining crofters security from eviction, the benefit of some improvements, and also introduced a court to set crofters’ rents, adjudicate on arrears and facilitate extensions to crofts. Although this was too late for many people, it significantly improved conditions for Highland crofters in the future.

A croft house in Breaclete. Breaclete is the central village on Great Bernera and inhabitants of the village would have participated in the Bernera Riot. © HES (Buildings of the Scottish Countryside Collection)

Over the 20th century, land buyouts by local communities have taken place in several areas, giving control back to the people who live and work there. There were just three land buy outs between 1908 and 1971. But since the 1990s more and more of Scotland’s rural communities have been able to purchase the land they live on for the good of the people who live there. And in 2003, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act granted communities the right to buy land within their local area.

Living in rural Scotland today

Living in one of the world’s most desirable and romanticised locations isn’t without its issues. Local communities are seeking to find the right balance when it comes to being a popular tourist destination.

Many visitors to the Highlands are descended from the very people who left during the Clearances. A love of Scotland and the Highlands has been passed down through the generations, and descendants of the people who were expelled from their homes are keen to explore their roots. And Scotland is renowned for its warm hospitality, stunning landscapes and rich culture and history.

A family visiting Fort George.

Local communities and businesses undoubtedly benefit from the tourism industry but it does bring its challenges – particularly around housing. Rural Gaelic communities are once again finding it challenging to make a life in the Scottish Highlands. The Highland Council’s Sustainable Tourism Strategy looks at the pressures and opportunities in detail.

There are people leading the way in trying to find balance between the needs of local communities and visitors all over Scotland, not just in the Highlands.

In 2017, Auchrannie resort on Arran became Scotland’s first employee-owned resort. Organisations like Scottish Community Tourism champion and support community tourism, which seeks to put communities and the environment first. And in the town of Kilmaronock, they’re exploring ways to repurpose their church for flexible community use, focusing on preserving its heritage for locals and visitors. This is a complex challenge with no simple answers but there are opportunities to share and learn as we go. Find out more in our Community Advice Hub.

Feature image credit: An old croft cottage by Drumbeg in Sutherland. © James Gardiner. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Find out more about this turbulent time in our blog about the Battle of Culloden.