We’ve all seen them, even if only in picture books – tiny, winged creatures, dressed in clothes fashioned from flower petals. They’re shy and elusive, but ultimately harmless, the stuff of nursery dreams.

Well, yes, if we are talking about the fairies of children’s tales, as popularised by writers like Mary Cicely Barker. They are politely presented in the colours of an English country garden. But these fey little beings would be out of place in the Gàidhealtachd (the area where Gaelic is spoken).

Their pastel camouflage would only make them stand out all the more against a rugged, heathery backdrop. Indeed, Barker’s ‘flower fairies’ scarcely seem to be related at all to the Gaelic fairy race, who hail from an older, darker tradition.

So gather round as we share sgeulachdan (‘stories’ – pronounced: skeea-lach-kin) to warn you of their wily ways. If you’re following our pronunciation guide, all the “ch” sounds in the Gaelic words in this blog should be pronounced like the end of loch.

Glenshee, known as the ‘enchanted glen’, has long been associated with fairies. It takes its name from the Gaelic word sìth, meaning fairy. Explore records relating to the Glenshee area on trove.scot © Courtesy of HES (Collection of watercolour sketches by ‘A.C.’ of views in the Highlands of Scotland)

How to address a Gaelic fairy

One question we’re asked a lot is “How do you say fairy in Gaelic?”

The fairies go by different names, all of them respectful.

The simplest is sìth, pronounced she. They’re also referred to as Na daoine sìthe (‘the peaceful people’ – pronounced: Nuh Duh-nya She-huh), or as ‘the good folk’, for example.

How to identify a Gaelic fairy

Stature

The fairy of Gaelic folklore is not a tiny creature at all, but of similar size to humans. Accounts differ slightly, but their size is only seldom remarked upon and where it is, they are described as being only slightly smaller than the average human being. There are, indeed, stories of human beings encountering fairies, but being unsure that they were not actually human. This would seem to imply little or no difference in stature. These are certainly not diminutive creatures, such as Thumbelina or Tinkerbell.

Physical differences

Aside from the occasional reference to height, a few accounts of fairies in the Gàidhealtachd refer to two other physical characteristics which are sometimes present. First, some fairies are described as having only one nostril. Second, female fairies are frequently described as having long, pendulous breasts. This latter peculiarity may well relate to another central piece of fairy lore, which we’ll explore a little further on: the changeling.

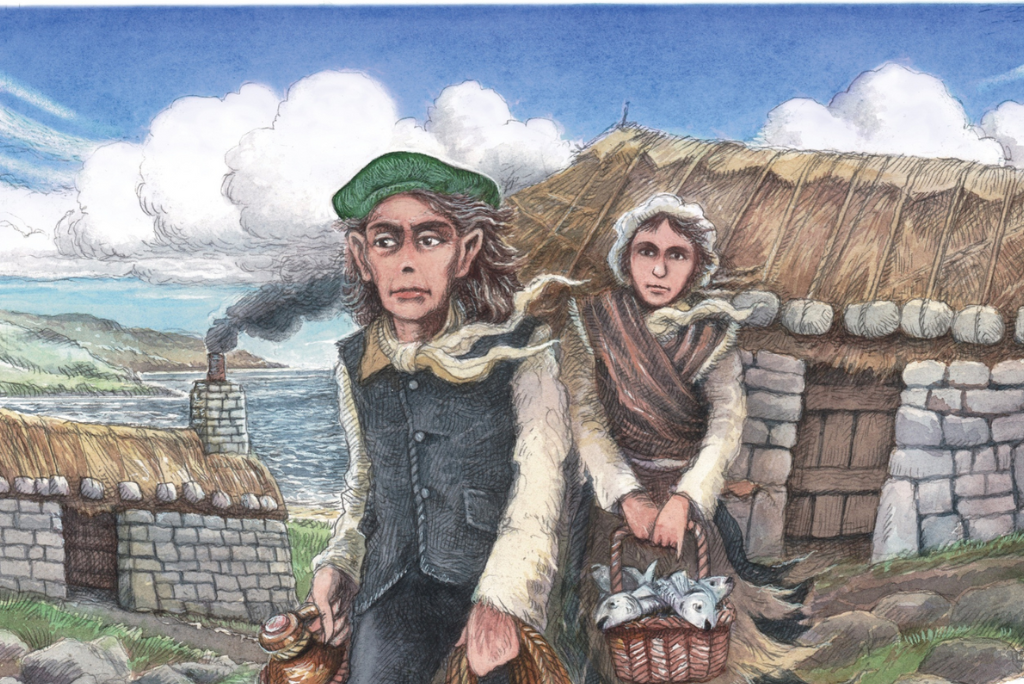

It could be difficult to recognise a fairy. They looked quite a lot like humans. Illustration credit: Brian Lee.

Dress

Their clothing, again, offers little in the way of clues to fairy origin. Like their human contemporaries, fairies dressed in the colours of the landscape. Homespun clothes, with only natural dyes available, creating a palette of dun browns and greys. The 19th century folklorist, Rev John Gregorson Campbell, mentions the occasional ‘blue bonnet’ among the Highland fairies. This would certainly cause them to stand out!

However, this may well be a mistranslation on Campbell’s part as ‘gorm’, the Gaelic word for ‘blue’ is also the word used to describe the kind of green hues found in nature. This would probably be a more plausible colour to find amongst the otherwise dull hues of the fairy wardrobe.

Cnoc Freiceadain long cairns are sometimes known as ‘Na Tri Sithean’ (the three fairy mounds). In trying to make sense of these unusual Neolithic burial monuments, later communities imagined they had their origins in the supernatural.

Fairy Behaviour

Social groups

Assembling what we have on record in relation to Highland fairy belief suggests that there are actually many parallels between their society and ours. Fairies, it seems, lived in family groups within wider communities. They had occupations and experienced the full range of human emotions. Furthermore, they had a mischievous side!

Indeed, their similarities – while retaining that essence of magic and mystery – to ourselves may be what made fairy belief so useful. After all, they are much easier to identify with because they are like us. They are familiar in their motivation and behaviour.

Ronald Black, editor of ‘The Gaelic Otherworld’, has likened the role of fairy belief in the lives of our ancestors to that of television soap operas in our own daily lives. Soap characters are like us – familiar, yet exotic. We can live vicariously through them, exploring how we would feel about, or react to, the dilemmas that they face in their lives.

The Blackhouse at Arnol. The people who lived her would likely have shared cautionary tales of fairy folk around the fire. Oral histories are a crucial part of Gaelic intangible cultural heritage.

Explaining the inexplicable

Modern research in a range of disciplines has expanded on the idea that fairy belief was a means of explaining and coping with difficult situations in real life.

It is widely accepted that our ancestors turned to the supernatural world for explanation of issues that they could not otherwise comprehend. Fairies were often blamed for a range of domestic mishaps, including missing items, or sick animals.

Research also suggests that those struggling to come to terms with infant and maternal death, or life-altering conditions in children, often turned to fairy belief. This served as a way to explain and cope with these difficult experiences.

Theft

Rev John Gregorson Capbell refers to the fairies as ‘felonious elves’, for they did, indeed, have a reputation for removing what was not theirs. However, Gaelic fairies did not steal in the way that a human burglar might. They may have taken the substance of the object or person, but they always left something behind. You could not quite say that they had left you empty-handed…

Milk snatchers

One of the commonest complaints against fairies in the Highlands and Islands was that they would, to use the Gaelic phrase, take ‘an toradh às a’ bhainne’ (the goodness from the milk). This was done whilst the milk was still in the cow. The person milking the animal was not left with an empty pail, but rather a quantity of thin, watery liquid with no nutritional value. This was typical of the fairy way of pinching: taking the best for themselves and leaving a mere imitation of the milk behind.

Fairies were notorious for stealing the best milk. Image credit: Kyle Stewart

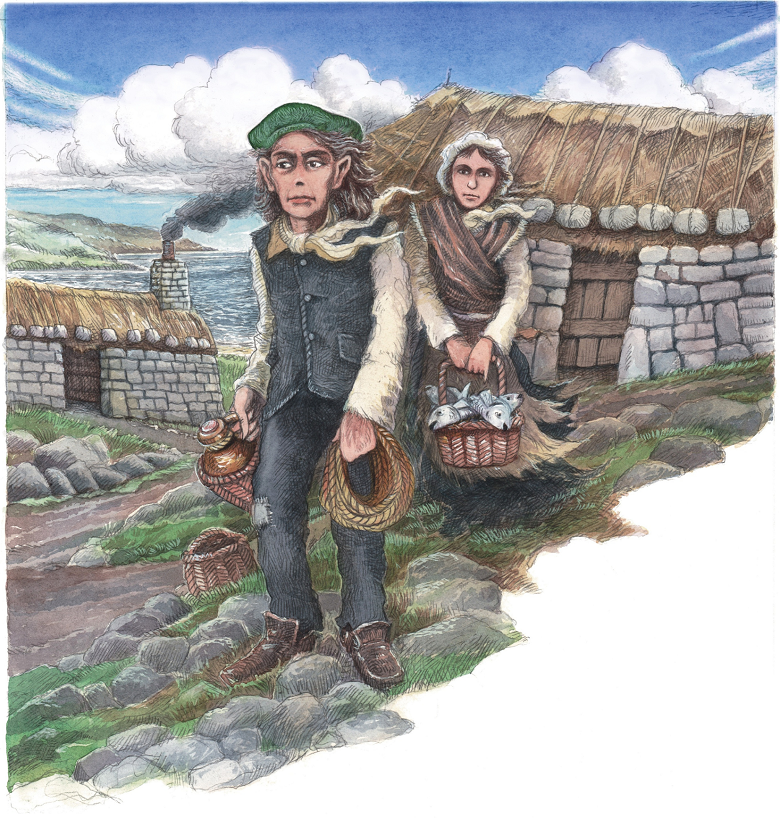

Changelings

Probably the best-known instance of fairy theft is the phenomenon known as the ‘changeling’, or ‘tàcharan’ in Gaelic (pronounced: ta-char-in). Stories abound in Gaelic folklore of babies being removed from their cradles and replaced with a fairy equivalent. Again, the human child is gone from his parents, but they are not left childless. They have a fairy to take care of.

Gaelic folklore suggests that the new occupant of the cot is not actually a fairy baby. Instead, it is a fairy bodach (pronounced: baw-dawch) or cailleach (pronounced: kal-yeeuch)—an old man or woman of the fairy race. Fairies supposedly coveted human children for their beauty. They devised a clever way to take them while ensuring their own elderly were cared for.

A feature of changeling stories is that the substitute ‘child’ has abilities or knowledge beyond its tender years. In one story from North Uist, a woman discovers her young baby playing the chanter in his cradle, for example.

A changeling was a substitute left by a fairy when kidnapping a human being. Illustration credit: Brian Lee.

They tend to have fairly voracious appetites, but not to grow any plumper or rosier as one might expect a well-fed infant to do. All of this lends credence to the theory that the folklore was created to explain that category of conditions in early infancy which one might describe as ‘failure to thrive’.

Occasionally, these stories will make reference to the mother having been lifted away by the fairies. It was believed that fairy women were unable to nurse their own children (perhaps as a consequence of their deformed breasts). Some stories have them being kidnapped to act as wet nurses in fairyland.

Reputation

There is a sense in which our ancestors seemed to live in awe of the fairies. Seeking always to appease them, lest the capricious fairy mischief be turned against them.

It’s impossible to say whether they were good or bad, for they had the potential to be either. While many of the changeling stories suggest that they only took children who were apparently being neglected, their interpretation of maternal neglect was very harsh. A woman who briefly turned away to do a household task could become a victim. They certainly did have the reputation of being benign in their dealings with children; adults were another matter.

Much like fate, they could treat you kindly or harshly. All you could do to protect yourself was to be as respectful as possible. That is why the Gaels were very particular about the way in which they referred to the fairy race. You never knew when they might be listening!

About the author

Catriona Murray, a Gaelic speaker, is a lecturer at the University of the Highlands and Islands North, West and Hebrides on, among other things Scottish Gaelic, social history of the Gàidhealtachd, “Islandness”, social and cultural anthropology, folklore, oral traditions, and oral history.

Read more

Check out more blogs about Gaelic culture and language.

Interested in learning about how fairies have left their mark on Scotland’s landscape? Join Ruairidh Maclean in exploring some of the Gaelic fairy place-names in Scotland in his NatureScot blog ‘Fairy Mountains of the Gàidhealtachd’.

Looking for a gift for the little bookworm in your life? Take a look at An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Folk and Fairy Tales. Award-winning children’s author Theresa Breslin has collected the best-loved tales from all over Scotland.