Who was Edinburgh’s top public architect?

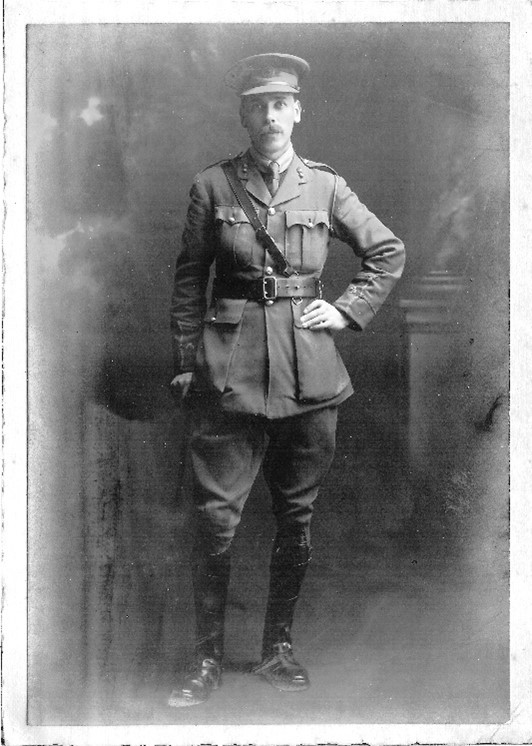

Born in Argyll in 1881, Ebenezer James MacRae grew up in a Gaelic speaking household. He was the son and grandson of Free Church of Scotland ministers. Educated and trained in Edinburgh, he joined the City Council in 1908 and after service in the First World War, he succeeded James Williamson as City Architect in July 1925.

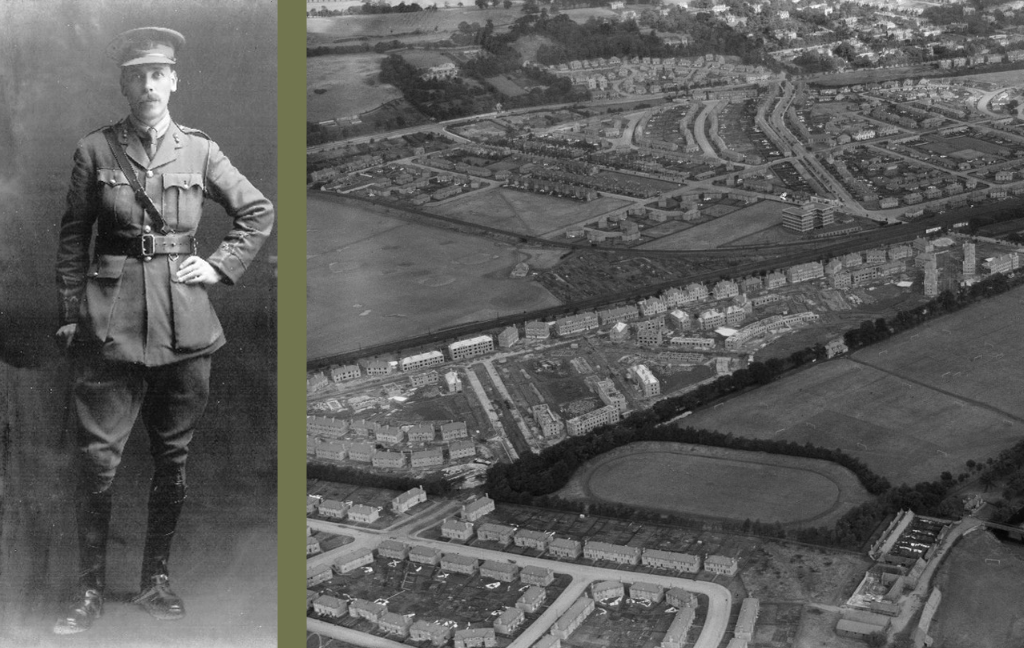

MacRae in the First World War – courtesy of MacRae’s granddaughter

As City Architect in 1936, he led a seventy-five people team made up of architects, clerks of works, technical assistants and administrators. His role involved the maintenance and design of a huge variety of council buildings, including washhouses, hospitals, libraries, schools and dozens of electricity substations. More unusual projects included beach huts at Portobello, a curator’s house at Lauriston Castle and a rural cattle farm to deliver tubercle-free milk to the capital.

Braid Hills Golf clubhouse, designed by MacRae’s team in 1932 © Crown Copyright: HES

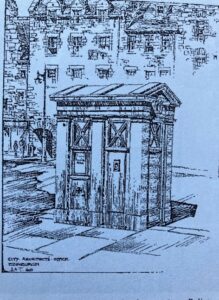

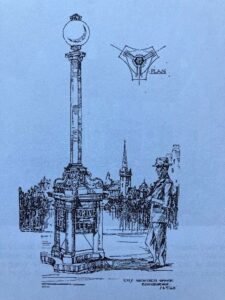

Smaller projects included public toilets, pavilions, potting sheds, and most famously, the police box – a bespoke design for the classical city. These designs have been covered in more depth in our previous blogs.

The Edinburgh Police Box – designed by MacRae’s team in 1930.

In mid-1926, MacRae replaced the Burgh Engineer, Adam Campbell, as Director of Housing, bringing council housing within his remit.

MacRae’s legacy

The inter-war period was a tough time to be an architect. Construction costs were rising during and after the First World War, closely followed by economic impacts of the Great Depression. Council work was often under strict cost constraints.

The most pressing problem the council faced was housing, with many city homes lacking basic amenities. There was also severe overcrowding, with many families living in one or two room houses. A series of ‘improvement schemes’ (slum clearance) removed the worst of the decaying Old Town and St Leonards, but did so sensitively. This often meant removing individual blocks, a process known as ‘conservative surgery’. This differs from the comprehensive redevelopment approaches seen in the 19th century and again after the Second World War in Leith and Dumbiedykes.

A series of new housing estates were built at Prestonfield and Niddrie, and in the 1930s MacRae’s new architects designed more architecturally noteworthy estates at Saughton Golf Course (Whitson), Craigentinny, and Craigmillar.

Whitson Crescent (Steven Robb)

MacRae pushed for new replacement homes in the city centre, building stone-fronted tenements to harmonise with the historic city.

Tenements at West Richmond Street, Pleasance (Steven Robb)

Examples can be seen in the Pleasance, Canongate, Gifford Park and East Crosscauseway. He also used stone in his more suburban schemes, like his masterpiece at Piershill.

Aerial view of Piershill, © Crown Copyright: HES

Piershill – showing harled and stone built tenements.

Maintaining Edinburgh’s historic character

Architecturally, MacRae was a traditionalist, building in masonry, with pitched slate roofs and timber sash windows. Despite being a key contributor to the Highton Report (1934) on contemporary European housing, he remained sceptical about continental modernism and communal facilities. His ideal was the three or four storey ‘reformed’ tenement, allowing higher densities, and helping tenants live near their workplaces.

MacRae was also sympathetic towards heritage, undertaking the restoration of Candlemaker’s Hall in 1930. One of his last actions was to publish important studies on Edinburgh’s historic buildings, a precursor to the listing system.

As the city council’s architect, MacRae was responsible in some way for the face of the city we see today. Unlike his namesake Scrooge, he had a real desire to help tenants thrive through decent new housing with good daylight, ventilation and amenities like gardens, schools and libraries.

By the time he retired in 1946 he had delivered around 12,000 new homes and a variety of significant public buildings, including the flanking extensions to the City Chambers and Portobello’s Power Station.

MacRae’s sympathetic extensions to the eighteenth-century City Chambers in Edinburgh’s High Street designed in 1932

MacRae’s team

MacRae spent little time at the drawing board himself, instead relying on his team. In 1926 he inherited architects from the City Engineer and later employed several young architects.

Sadly the city council retained no staff records, but the Dictionary of Scottish Architects (DSA) has attempted to reassemble his team from a variety of sources, including original drawings. With this detective work it has been possible to build up a picture of the Department and the authorship of many buildings.

I’ve recently been updating and adding new entries to the Dictionary of Scottish Architects, to explore the often-forgotten people behind MacRae’s work.

Who were the team?

A recent and previously unrecorded architect is Tom Smith, who worked with MacRae’s predecessor Williamson. He was responsible for housing in Portobello High Street and designed the major estates at Pleasance and Craigmillar.

Another is James Tweedie, whose father and brother were both architects but never himself joined the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). He was lead architect for the Union Street Public Washhouse and provided some wonderful sketches of the City’s police boxes and street signs.

Leith-born Peter Rice Whiston joined MacRae’s team in 1930 and helped design a housing scheme off Leith Walk. After the war he became Chief Architect to the Scottish Special Housing Association and later specialised in traditional ecclesiastical work. In 1951 he designed the Sancta Maria Abbey in Nunraw, listed at category A in 2017.

David Gordon Bannerman worked under MacRae from the mid-1920s. He later became the Chief Architect for Lanarkshire Council, designing Lanark’s County Buildings in Hamilton in 1959. The offices were inspired by the United Nations building in New York and are also now category A listed.

Lanark’s County Buildings in Hamilton © Crown Copyright: HES

James Moffat Aitken was one of MacRae’s appointments in the late 1920s. He designed the attractive housing at Gifford Park between Clerk Street and Buccleuch Street. He later became the Chief Architect, then Chief Planner in Northern Ireland; designing the New Town of Craigavon.

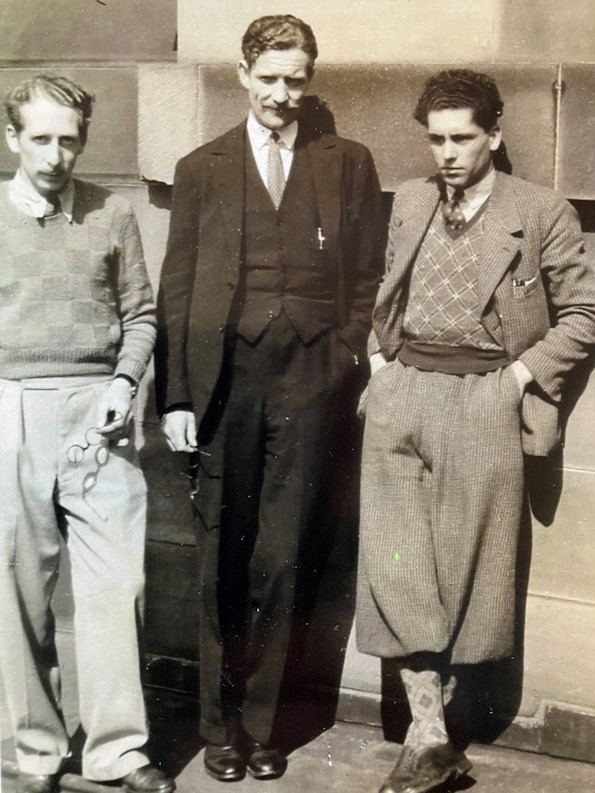

Three of MacRae’s architects – from left James Moffat Aitken, George Clark Robb and unknown (Steven Robb)

It is interesting to see some early women architects including Elizabeth Fergus Comrie, who designed a tenement block at Craigmillar, and Annie Nicol Turnbull who worked under MacRae in 1935. At this date there were only 130 qualified women architects in Britain. In 1948 Turnbull became Dunfermline’s planning officer. She was a very early Scottish Planner and the first female planning officer in Scotland.

My own great uncle, George Clark Robb, built upon his experience with MacRae designing thousands of council homes for Leeds, Oxford, Stirling and Aberdeenshire Councils. He would eventually become a planner with the Department of Health and Scottish Development Department.

Find out more

Looking to find out more about MacRae’s housing in Edinburgh? Take a look at my article in the Book of the Old Edinburgh Club.