Have you heard the story of Dr James Barry?

His name is becoming more familiar nowadays, but after his death he was hidden from history for a century.

Why? Well, he wasn’t born a man. He was what we would call today transgender.

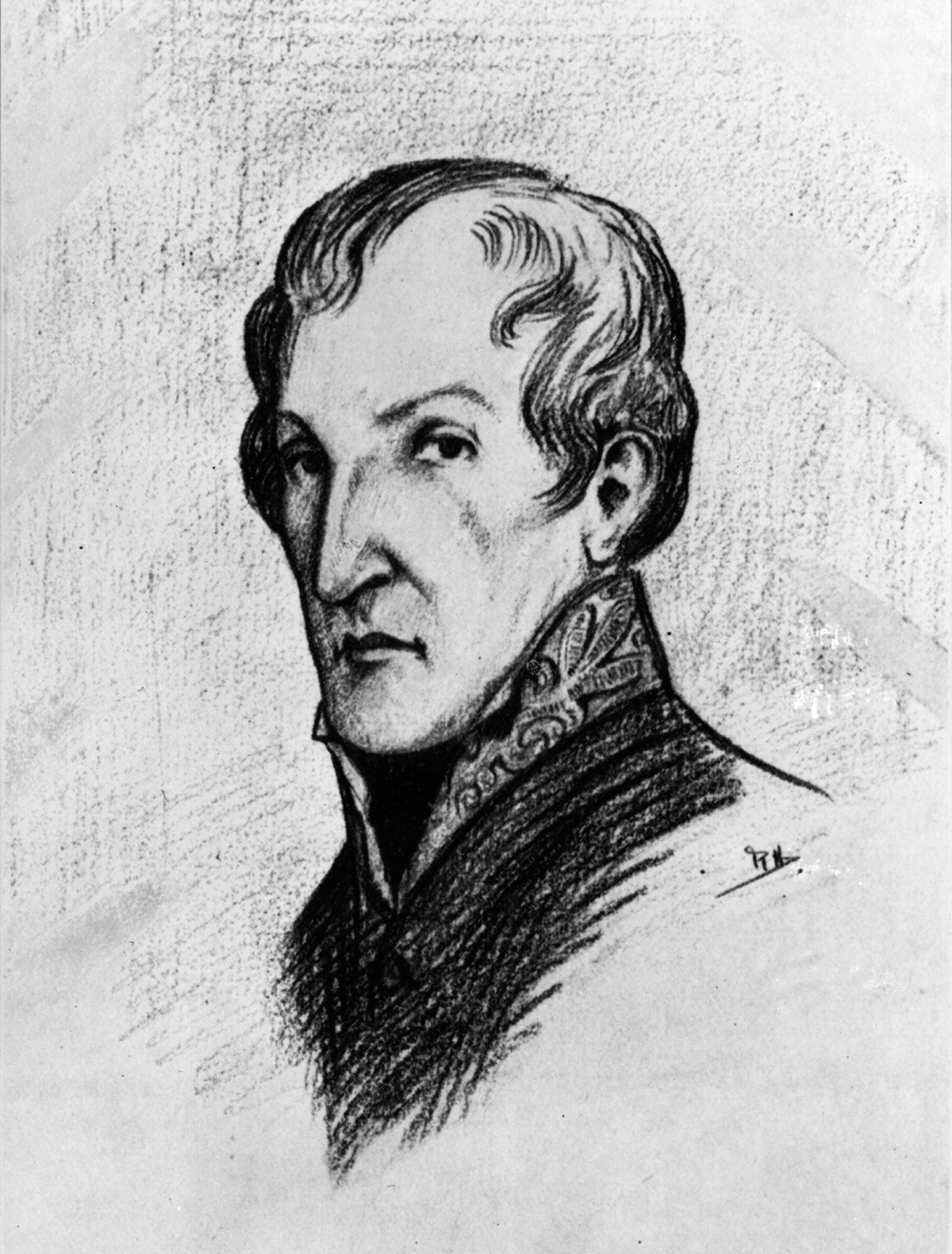

Dr James Barry. Image credit: Wiki Commons

Where and when was James Barry born?

Born in Co. Cork, Ireland in 1795, James adopted his new name from his uncle, and moved to Edinburgh to study medicine at Edinburgh University.

He was able to pass as a man, with other students and tutors assuming he was perhaps just lying about his age (based on records he would have been 15 when he started university), rather than his assigned sex.

After graduating in 1812, James joined the military as an assistant in the military hospitals. He did this until 1817, when he was deployed to South Africa, moving between Cape Colony (Cape of Good Hope) and Mauritius.

The Cape of Good Hope ©Cairns Aitken. Courtesy of HES

What was James Barry famous for?

His career in the army moved quickly, partly because of his ability to bond well with senior officers such as Lord Charles Somerset, and partly from his dedication to his job. Dr Barry became the personal doctor to Somerset and his family and in return was promoted to Colonial Medical Inspector.

The relationship between James and Lord Somerset was a strong one, with James being returned to England to care for Somerset in his final years. The closeness of the relationship may suggest the Lord knew of the doctor’s situation.

One article from the Royal College of Surgeons uses the term “favourite”, which sometimes implies an intimate relationship in queer historical circles.

We can’t know the exact nature of the relationship between Barry and Somerset, so it would be unfair to speculate beyond a close bond, perhaps shaped by the constraints faced by the men at the time.

Barry provided a juxtaposed masculinity. He was known for carrying a rapier which he was very skilled with, as well as his pistol which he used for duelling; and routinely got in loud, aggressive arguments with people.

All this while also being shorter than many of the upper class gentlemen around him, with padded shoulders, a slightly higher voice and red hair. These factors could have left him open to ridicule, if not for his bulldog personality.

A Percussion Pistol made in the 1800s

James Barry’s Growth Mindset

James, unlike many doctors of the time, focused on continuous learning and skills development, learning from his experiences and from the local populations during his deployments.

It was during one of these deployments in Africa where he learned from the indigenous midwives how to successfully perform a C-section that saves both mother and baby – something modern medicine in Europe had yet to achieve.

In return for his education, Dr Barry made great efforts to improve health at the camps and outposts under his care, not just for the soldiers and families but for the workers, enslaved people and locals living nearby.

This didn’t just mean moving the toilets away from the canteen and drinking water. His work was invaluable to the development of modern medicine, in saving people’s lives and promoting a better standard of living. Part of this included the development of a leprosy sanitation camp in Cape Town.

Barry vs Nightingale

During the Crimean war, Dr Barry was appointed within the same hospital as famous nurse Florence Nightingale. The two were both incredibly influential medical professionals, but they didn’t get on.

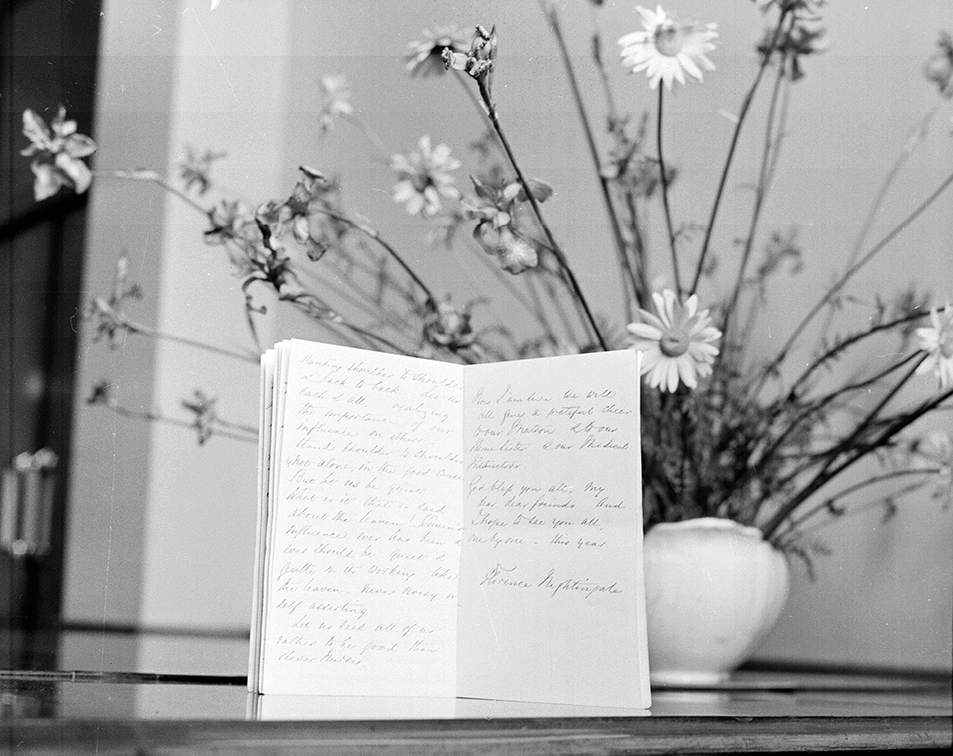

A letter written by Florence Nightingale at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary ©The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Courtesy of HES

Barry knew that in the war hospitals, hygiene was top priority as most soldiers were dying from disease and infection rather than their wounds, which Nightingale discovered and reported after the war.

Nightingale, still in the early years of her work at this point, was less aware than Barry of the consequences of poor hygiene. Her focus at this time was on whole body health, including the morale of the patients.

Nightingale recounts after James’ death an incident where the doctor berated the Nurse in front of a courtyard full of people, saying she never met someone so harsh.

You might have read that it was Nightingale who improved hygiene within the field hospitals. In fact, this was not attributed to her until 1912, long after the fact – and long after the British Forces tried to expunge records of Dr James Barry.

Following her experiences in Crimea, Nightingale began campaigning for increased hygiene standards in hospitals. Her statistical studies also demonstrated the importance of this. Her focus on proper diet, round the clock care and whole-body health is still part of the underpinnings of medicine today.

Together, they could have done rather amazing work in the development of the field of public health, but Dr Barry was not in the habit of making friends.

Surgeon Munro’s surgical instruments. Stirling Castle.

How did James Barry Die?

Dr James Barry died in 1865 in his home in London of dysentery and strictly forbade an autopsy or for his body to be washed – which he was denied.

The mortuary assistant who performed the washing and cleaning of Dr Barry’s body discovered and reported the difference between his stated gender and his physical sex. She even claimed that she could tell Barry had previously given birth, though there are no records to support this.

Sketch of Dr James Barry, ©Hulton Getty. Courtesy of HES.

We do know that the eminent surgeon was born as Margaret Anne Bulkley, and that in living as James Barry from a young age he was able to have a life he never could have done otherwise.

Barry travelled the world, attended medical school and made pioneering changes in the medical field more than 50 years before the Edinburgh Seven became the first women to study medicine in Britain.

The army had his records sealed for 100 years after his death, but they were opened again in 1965. His story is just one that can now be researched and and told, helping to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of LGBTQ+ history.

If you’d like to read more stories that bring Scotland’s hidden queer history into the light, you might like our book, who will be remembered here.