Please be aware that this post contains descriptions of violence against women⚠️

Walking through Holyrood Park, you might have come across an unassuming stone cairn. For centuries, this memorial marked the site of a brutal crime—the murder of Margaret Hall by her husband in 1720. Today, the cairn has been reclaimed as a tribute to Margaret herself, shifting the narrative from her abuser to her life and legacy. Read on to uncover what we know about Margaret’s life.

Margaret Hall’s Story

We know little about Margaret Hall’s short life outside of her marriage. From parish records, we know that she was born in Edinburgh in 1703. Her father was a tavern owner on Castle Hill. This historic area forms the top of the Royal Mile, leading directly to the Edinburgh Castle esplanade. The cobblestone streets and historic architecture are now a favourite with locals and tourists alike. In the 1700s, Castle Hill was a bustling area which housed some prominent residents in Edinburgh.

At her father’s tavern in this busy area, Margaret met Nicol Mushat, a man eight years older than her, who charmed her and proposed marriage after just three weeks. Margaret’s father would have seen Mushat’s proposal as advantageous. He was a medical student with a minor title, from a relatively wealthy family.

Margaret married Mushat on 5 September 1719, aged just 16. Mushat quickly tired of his young new bride. He first schemed to abandon and divorce Margaret, defrauding her of financial support. When attempts to isolate Margaret and damage her reputation failed, Muschat’s abuse escalated, and his thoughts turned to murder. With accomplices, he tried repeatedly to poison her using mercury dichloride, then a common treatment for syphilis, disguised as medicine. Despite severe illness, Margaret survived these attempts. Other schemes followed: plans to drown her, push her from a horse, or strike her with a hammer, all of which failed.

Finally, Muschat resolved to act alone. On the night of 17 October 1720, he stole a knife from his landlady. He then persuaded Margaret to join him on a walk to Duddingston Kirk, under the guise of reconciliation. Near the spot marked by the cairn today, he ended her life in a deliberate act of violence. Her body was discovered the next morning, bearing evidence of a struggle.

“All Hearts Be Swell’d with Grief”

Margaret Hall was an everyday middle-class woman. We know that violence against women during this time was sadly not unusual. However, the level of violence inflicted on such a young woman by her husband was outrageous and horrifying to the public at the time. The campaign of abuse against Margaret, as well as her brutal murder, certainly did not go unnoticed or unmarked.

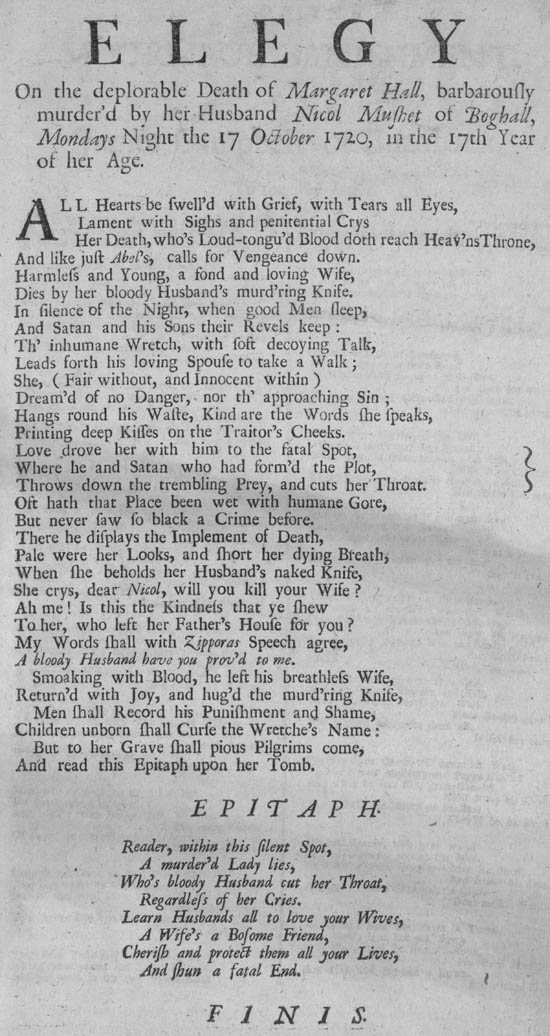

“Elegy on the deplorable death of Margaret Hall” printed in Edinburgh, 1721. From the National Library of Scotland.

Much of what we now know about the crime comes from sensational newspaper accounts. Newspapers produced elegies and epitaphs in ways we would now see as popularist, or even ‘click-bait’ content.

Newspaper accounts of the crime fuelled public outrage. Mushat confessed, and his own mother disowned him. He was tried and executed, with his body displayed as a warning to other could-be criminals. But Margaret’s story did not end there.

A Memorial Cairn

Aerial view of Holyrood park from Trove archives. The small cairn can be seen in the middle, just before the point where the two roads meet.

The 18th century origins of Margaret Hall’s memorial cairn are obscure. We don’t know how the cairn came to be constructed. Some suggest that local people raised subscriptions to fund construction of the cairn soon after the murder, but evidence of the cairn in this period is limited. We do know that by the early 19th century, the cairn had largely faded from memory—until Sir Walter Scott revived public interest.

In 1823, Scott oversaw the cairn’s restoration. The cairn we can see today is in a different location than it was originally. Its present location is associated with Scott’s ‘Heart of Midlothian’ novel. Scott is well known to have contributed to the romanticisation of Edinburgh and its past, and the cairn may well have been a part of that. However, Scott’s involvement only adds to the cultural significance of the site. Margaret’s story clearly managed to capture the hearts of Edinburgh’s people both in the 1720s and again in the 1820s. Despite radically different societies of the 18th and 19th centuries, this story of domestic violence still managed to hit home, as it still does today.

The Naming of a Cairn

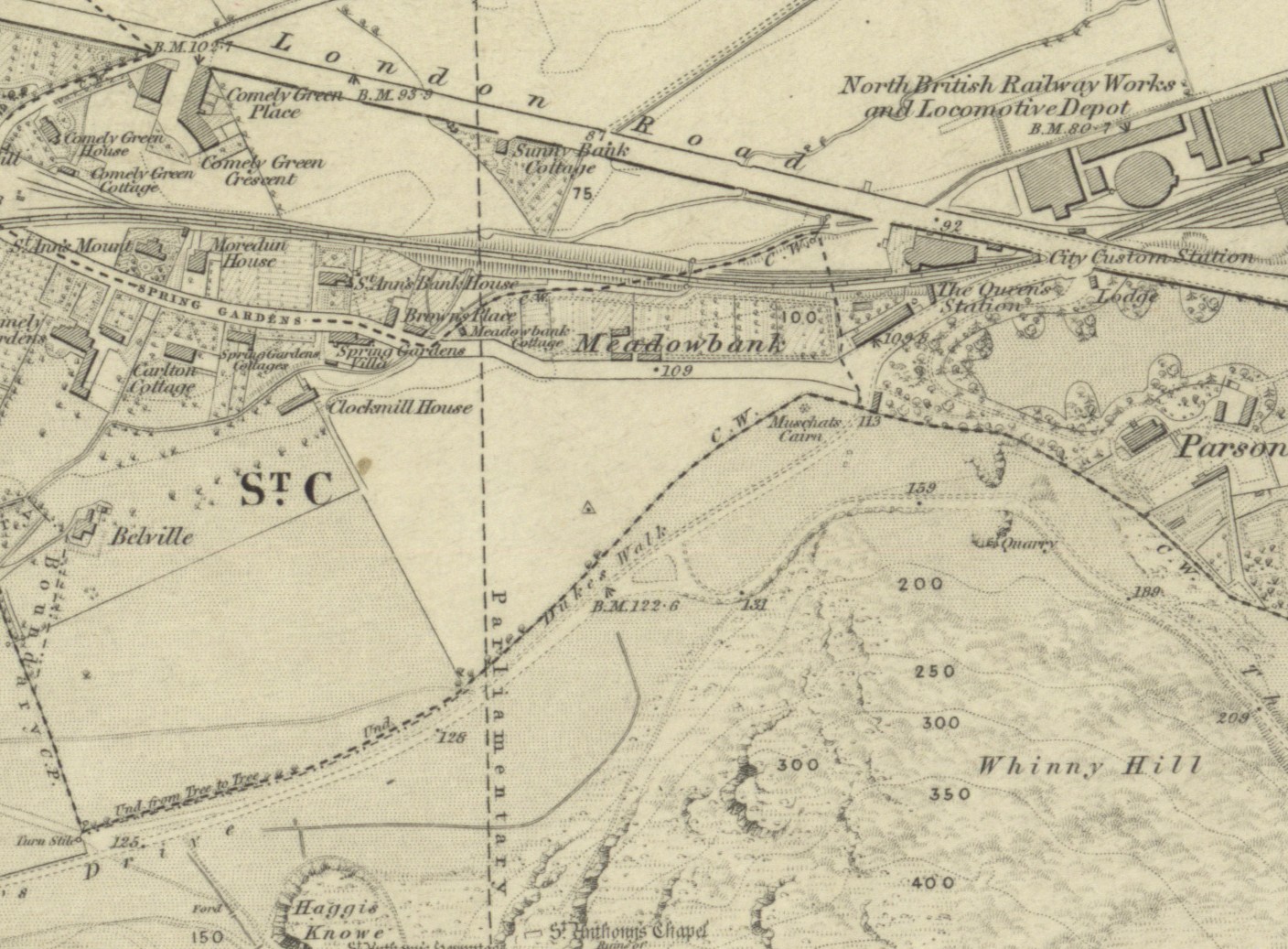

Part of a map of Edinburgh (1853) that shows ‘Muschats Cairn’ in Holyrood Park. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland: CC-BY

For centuries, the cairn stood as a memorial to Margaret. However, it was known as Mushat Cairn (with varying spellings), bearing the name of her abuser. Sir Walter Scott’s involvement, despite being a restoration effort, also served to muddy the Cairn’s legacy. For those who knew the story of the cairn, this unassuming pile of rocks brought to mind the names of two men – Mushat and Scott.

That changed in 2024. Sara Sheridan (author of Where Are The Women?), local historian Andy Arthur, and a team of committed activists campaigned for the Cairn’s name to be changed. Their work coincided with a Scottish Government bill aimed at helping to prevent domestic homicides and suicides, to prevent modern versions of Margaret’s tragic story.

The official name of the cairn on Ordnance Survey maps now honours Margaret Hall, not her killer. The cairn has always been Margaret’s. This re-naming makes the cairn a testament to a life cut short rather than a monument to violence.

A New Interpretation

Alongside the renaming, our interpretation team worked on a new panel to tell Margaret’s story. They worked closely with Women’s Aid and the Scottish Government’s domestic homicide team. They aimed to re-focus the cairn on Margaret herself rather than her abuser, and to present her as more than just a victim.

The new panel in Holyrood Park gives visitors information about the cairn and its significance.

We don’t know what Margaret looked like as no records survive. The panel includes an artist’s impression of her, wearing clothing typical of a middle-class woman of her time. The painting by young Scottish artist Izzy Collins brings Margaret to life. She is holding a glass (a nod to her abuser’s poisoning attempts), and meets the viewer’s gaze. This gaze forces us to acknowledge the events we know from her life, bridging past and present.

Margaret Hall’s Cairn is now the only feature in Holyrood Park with a distinct interpretation panel. In a city where statues of men dominate, this cairn stands as one of the few monuments in Edinburgh dedicated to a woman.

The Legacy of Margaret Hall’s Cairn

The cairn as it stands now in Holyrood Park.

Margaret Hall’s story resonates because it reveals so much about Edinburgh’s past, and our present. In the 1720s, her murder sparked outrage and moral debate. In the 1820s, Walter Scott’s romanticism turned it into cultural myth. Today, it speaks to ongoing struggles against domestic violence and the importance of naming and remembering women.

Next time you walk through Holyrood Park, pause at the Margaret Hall Cairn. Reflect on the young woman whose life ended there, and on the historians and activists who reclaimed her story. This memorial is a call to action, reminding us to stand against domestic violence and honour the lives behind the headlines.

Looking for more women’s history in Scotland?

From A Scottish Adventure with Anne Lister, the real Gentleman Jack to the Scottish Women’s suffrage movement, you can explore more women’s history on our blog.

Sign up to our blog newsletter to get the latest stories straight to your inbox.