We have always celebrated and enjoyed holidays in the cold heart of winter in this region of the world. How cultures and societies of the past celebrated Christmas, and the winter season generally, is one of the easiest and clearest ways to see the how similar our traditions are to theirs.

However, we can also see how different winter holidays were before they became more standardised in the last two centuries.

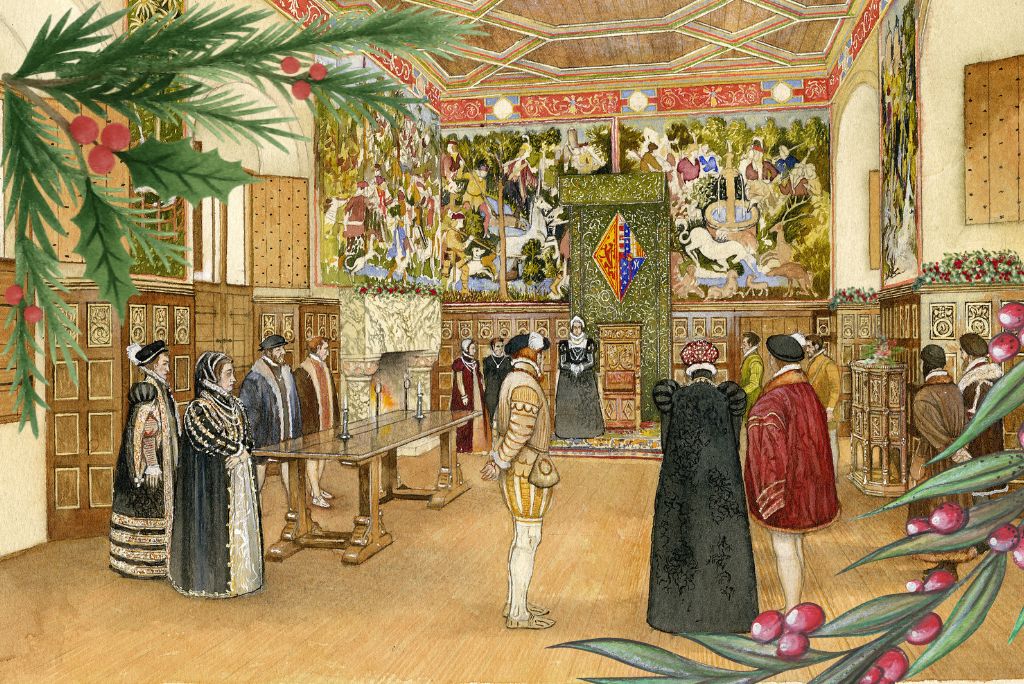

If we were dropped into James IV’s court, we would likely not understand others, or be understood ourselves. The Scots language of that era might sound faintly familiar, yet following a conversation would probably be challenging. But in spite of the language barrier, what might we recognise of Yuletide at the King’s court?

A blend of traditions

Before the Reformation, Scotland and England celebrated the Christmas season with traditions which blended Pagan and Catholic customs.

In order to explain the non-religious aspects of Christmas, the church often claimed these practices originated during the rule of King Arthur. This explanation made these aspects just acceptable enough to get away with them. It would never have done to embrace traditions originating from the Norse Yol or Roman Saturnalia!

Many elements of Christmas we know today did not take place in the Renaissance Scotland royal household. For example, we would not see Christmas trees being decorated and used to place gifts under. This only became a tradition during the nineteenth century.

Similarly, gift-giving was not as universal and excessive as today. Santa Claus was not a celebrated figure. December and the twelve days of Christmas was devoted to St Nicholas and the Nativity. However, a lot of their traditions are recognisable enough to us.

Parties and Decorations

Most recognisable to us would be the fact Yuletide was a major celebration. A large amount of Crown expenditure went towards lavish food provisions and decorations at this time of year. Many courtiers and clerics would gift the monarch game especially for the Yuletide feasts. King Arthur was used as an excuse for the yearly indulgence in extravagant feasting.

Unlike the English Tudor royal court, Scotland’s monarchy remained itinerant. This meant that the court would move between castles and palaces throughout the year.

During James IV’s reign, Yuletide was celebrated at diverse locations like Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood, Aberdeen, St Andrews, Linlithgow and even Arbroath. By James V’s reign it was usually at the largest residence, Holyrood, but still occasionally elsewhere like Linlithgow in 1539.

King James IV and his royal household celebrated Christmas at various different locations over the years. Take a closer look on trove.scot. © Hulton Getty licensed via SCRAN.

While the Stewarts lacked Christmas trees, it was common to decorate with mistletoe, ‘holm, ivy, bays’ and any other evergreen plants.

The Yule-Log or ‘Yule-Stok’ in Scotland was not a tasty chocolate desert back then. Instead, it was the ritual of bringing in a real wooden log to burn and heat one’s residence the whole twelve days of Christmas.

Royal gift giving

With the Scottish monarch, gift giving while not as formalised an event as at the Tudor court. And nowhere near the gift-giving of our modern society!

However, the Stewarts did gift senior courtiers with presents, usually of gold, silver or precious jewels.

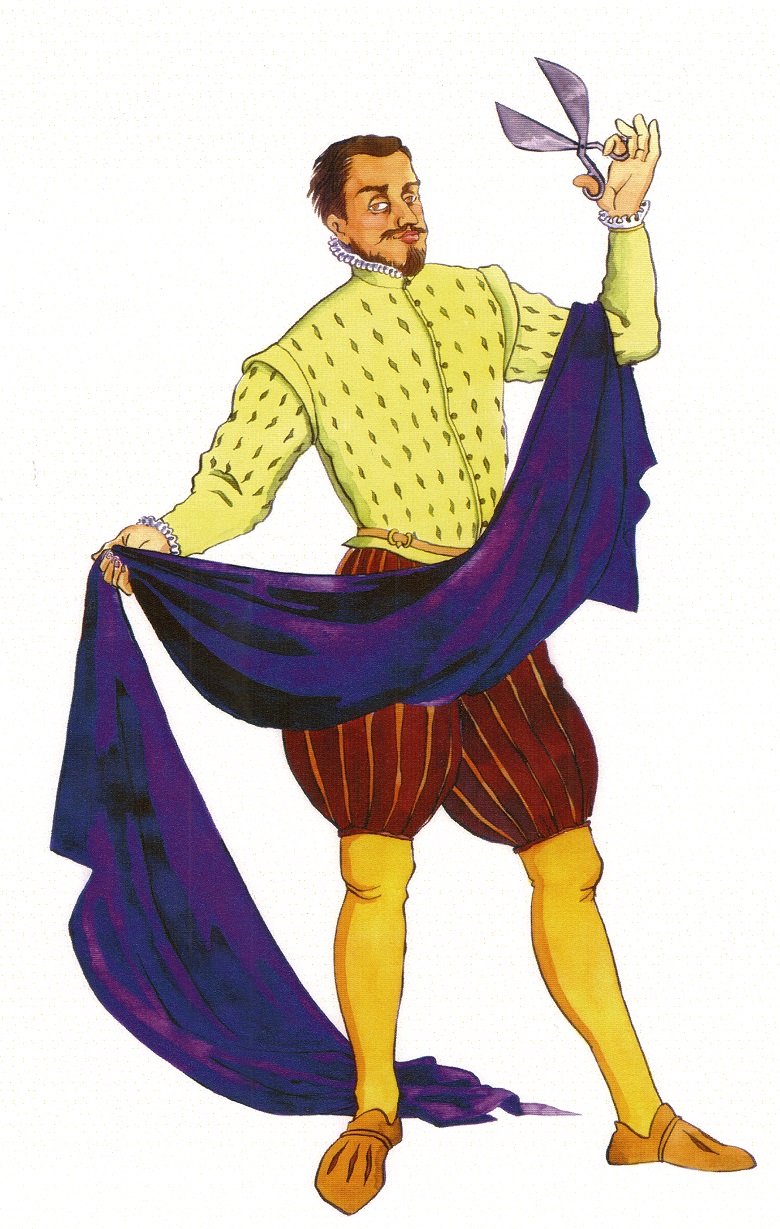

Quality fabrics were often given as gifts to favourite members of the household.

While in Paris during 1537, James V gave an array of expensive gifts to the French royal family, household officials and minstrels. Then, in winter of 1538-9, James V spent 400 pounds and 19 shillings on gold and silver gifts for his courtiers.

Christmas or Yuletide was also a time in which the royal household and their extended entourage received livery and monetary rewards. The treasurer’s accounts show this yearly across all sixteenth century Stewart monarch reigns.

Festive fools

Much like we do today, the Scottish royal household kept winter’s cold and darkness at bay with mischievous festive fun and games. As I explored in my last blog, neurodiverse fools were vital entertainers at Scottish royal courts and companions to monarchs in their household. At Yuletide they were especially appreciated.

During James IV’s reign, for instance, the man who looked after Curry the fool was paid to take him to wherever James was celebrating Yuletide. In December 1502 the fool and his man got 7 shillings to ‘haf him to Arbroth agane Yule’. He then went from Dundee to Edinburgh Castle in January to meet the King again.

Illustration of Curry by Thomas Secmezsoy-Urquhart

Court fools were not the only entertainment, however. Especially under James V, the court enjoyed the creation of, or watching of, interludes and plays. The earliest version of David Lindsay’s satirical play ‘Ane Satyre’ was shown at court on Epiphany (6 January) 1540.

Costumes used for theatrical performances or fancy‑dress occasions were also paid for by the treasury. In 1526 the treasurer had £40 ‘play coitis agane Yule’ provided. A sum of 40s went to buying ‘one play coit’ for an illegitimate son of James V, while a ‘play gouinis’ went to the King allowing him ‘to pas in maskrie’ in 1534. In 1540 similar play coats of red and yellow were bought.

The freedom to fool!

For ‘natural fools’, being a fool wasn’t just a role; it was a way of life. They often enjoyed certain privileges, such as the freedom to speak truth to power without consequence. Because they were neurodivergent, this license was theirs year-round and for life.

During midsummer and Yuletide, however, some non-disabled individuals were temporarily granted similar freedoms as “seasonal fools.” These were usually lower-ranking household servants chosen to play the part. In Scotland, chosen participants took on titles like Boy Bishop, King or Queen of Bene, Abbot or Prelate of Unreason (or Bonnacord), and even characters such as Robin Hood. In England, the title Lord of Misrule was used. These figures weren’t limited to winter, they also featured prominently in May Day and Easter festivities.

Such seasonal fooling began on 5 and 6 December, St Nicholas’ Day Eve and St Nicholas’ Day.

Saint Nicholas, Henderson Memorial Window, Dunlop Parish Church © Crown Copyright: HES. View on trove.scot.

Boy Bishops

Boy Bishops (members of a church choir) were assigned by the other members of the choir, and got to indulge as a temporary child bishop in church rituals, and fun and games.

James IV was visited by two Boy Bishops a year from Holyrood and Edinburgh St. Giles’ churches. Accounts show he gave them money ranging from 36s-£3 12s. By James V’s reign this tradition stopped at court, though the boys still ruled outside for slightly longer.

Queen of ‘Bene’

Then there was the King or Queen of the ‘Bene’. This figure was the origin for a tradition which still exists today. If someone finds a coin in a Christmas pudding, they are granted a prize or power over others at a yuletide celebration. The bean king/queen was chosen on ‘Uphaly Day’ or Twelfth Night from the late fifteenth century onwards if they found a bean in their Christmas pudding.

An un-named man in 1489 got 18s as ‘King of the Bene’. A John Goldsmith of the Chapel Royal in 1496, and Jock Pringle a trumpeter, were appointed as king of bean in other years.

In the winter of 1531, a Ms. ‘Christian Rae’ ruled the royal household games as ‘Queen of the Bean’. She got 3 ells (an old unit of length for fabric) of ‘riffillis blak’ cloth.

At Mary Queen of Scots’ court the roles continued to be present, as letters by ambassador Thomas Randolph to Robert Dudley in 1564 relate. Everyone had to pay these figures certain fees or face tricks and sanctions.

The Good Robin Hood

At the Yuletide court, you might encounter an Abbot of Unreason or the Abbot (or Prior) of Bonaccord.

These satirical figures could encourage risky behaviour. For instance, in winter 1496, an Abbot of Unreason’s Yuletide damage to the ‘hous’ of a Gilberte Brade was paid for by the Treasurer.

The figure of Robin Hood gradually came to replace figures such as the Boy Bishop and the Abbot of Unreason. Unlike them, Robin Hood was believed to be extremely devout and so more acceptable to the clerical and secular authorities.

Engraving by W. Ralston illustrating the ballad Robin Hood Rescuing Three Squires. Though rooted in English tradition, Robin Hood ballads were also sung in Scotland and featured in Lowland May Day festivities. (Published 1886.) Licensed by Glasgow School of Scottish Studies licensed via SCRAN. Find out more on trove.scot.

The end of an era

From the 1550s, however, this somewhat familiar jolly Yuletide of Yesterday began to disappear. Attempts to make seasonal fooling more acceptable by replacing satirical church figures like Abbots with Robin Hood could not stop royal and church authorities alike deeming these figures signs of public disorder and a threat to their power.

The 1555 parliament of Regent Marie de Guise declared going forward that ‘na maner of’ seasonal fool figures like ‘Robert Hude nor Lytill Johne Abbot of vnressoun Quenis of Maij’ would be permitted. Those who persisted in performing such roles would be banished from Scotland.

Yet for years after, occasional Abbots of Unreason to Robin Hood figures would appear in burgh records across Scotland.

Christmas cancelled

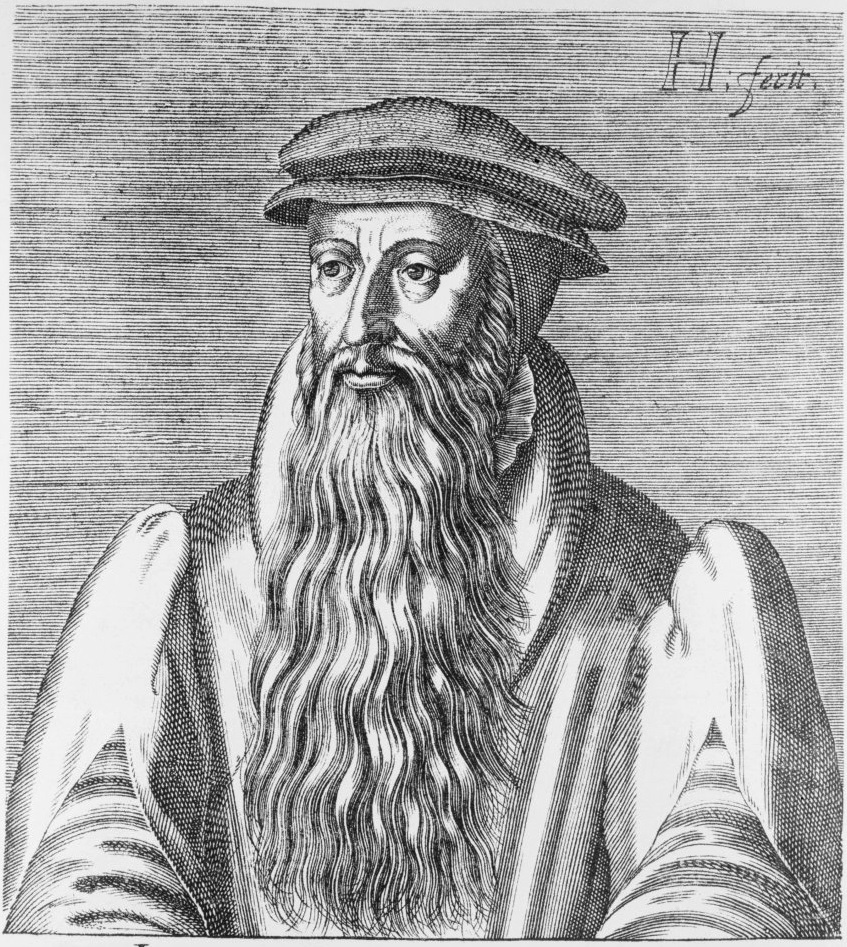

The final death knell for Yuletide came with the Reformation. From 1560 via the First Book of Discipline and their new policies, the Reformed Church and Kirk decided to stamp out all celebrations of any holiday or saint day, including Yuletide.

The Kirk (Church of Scotland) under Knox saw Christmas as a leftover from Catholicism, full of superstitious and extravagant practices. © Licensed by Hulton Getty licensed via SCRAN.

The First Book declared Non-religious Yuletide traditions like feasting or having seasonal fools ‘abominations’. The pagan and papist focus on festiveness was in their view a threat to a ‘godly life of moral disincline and prayer’.

Like the secular Scottish parliament act, this was initially not taken seriously or fully incorporated into Scottish society. The Kirk often spent time and effort punishing those who took on the positions or still celebrating Yuletide.

As the Kirk grew in power resistance ended. By 1640 it was established in British law that all holidays including Yule were ‘now purged’ from Scotland. English clergyman, Robert Jamieson, observed that Scottish minsters forced wives and servants to work ‘upon Yule day’, at odds with practices in England. The ban in Scotland remained. For over three hundred years…

Modern Yuletide

In fact, Scotland’s ultra Presbyterian approach to Christmas had an impact on my own recent ancestors. My paternal grandparents were married on Christmas Day, 1952. For them, and all Scots back then, this was a date no different to any other. Hogmanay was the only winter public holiday here.

Christmas pudding being prepared at Dreghorn Camp. Major D. Fraser stirs the mixture while Major Ravenscroft adds the traditional six‑pence coin. You can find out more about this photograph and its story on trove.scot. © Licensed by The Scotsman Publications Ltd (project 501) via SCRAN

It wasn’t until 1958 that the Christmas of pre-Reformation Scotland returned to these shores as a holiday. This year we will still only mark the celebration of the 67th Yule since the Reformation. Your own family likely still have living relatives who remember a Scotland without Yuletide.

History can often feel remote from us. However, in many ways the Scottish world of James IV’s and Mary Stewart’s reigns feels closer to our own world and its holidays or traditions than that our own grandparents and great grandparents grew up in.

Following the path of how we got to where we are today can be full of interesting surprises!

Want to know more about Christmas in Scotland?

- Take the Christmas quiz! Which figure from Scottish history would be your perfect Christmas dinner guest?

- Find out how Mary, Queen of Scots celebrated Christmas.