When you walk through the grounds of Duff House today, you’ll find an early Georgian mansion standing proud against the landscape. The imposing façade tells a confident story of 18th century ambition. The grounds tell a different tale: of paused plans, and a landscape that never became what its famous architect imagined. This is the story of William’s Adam’s lost vision – a garden that never grew.

A tale of two Williams

“View of the town of Banff with Duff House and The New Bridge” (after 1779). NRHE SC1436063 © Courtesy of HES. View on Trove.

Duff House was a hugely expensive project. Its owner, William Duff, Lord Braco (later 1st Earl of Fife), had grand ambitions for the house. It was to be his chief seat, and a sign to the world of his success in both business and politics.

When Duff House was commissioned in 1735, William Adam was the leading architect in Scotland. He was also one of the leading landscape designers in the country. Adam was involved in the creation of quite a few gardens, but Duff was the only one where he was working on a large scale at a completely new site.

A house without its setting

For more than 20 years after it was built, Duff House stood forlorn in an empty landscape. In the early decades of the 18th century, Scottish landowners were gripped by a fever for tree-planting and agricultural improvements. Therefore it was highly unusual to see a magnificent new house standing in a barren landscape.

Something had gone wrong. Lord Braco had fallen out spectacularly with William Adam over the cost of the building work for the house. By the early 1740s, Braco owed Adam over £5700 – a huge sum at the time (over £970,000 in today’s money). Adam sued Braco for the money. Although Adam won the case, Braco was determined to wear him down with continual appeals.

Of course, it wasn’t intended to turn out that way. Braco highly esteemed Adam’s skills as a designer “in other things of Ornament and Beauties of a Country Seat, besides the bare architecture of the house”. In 1735, only a few months after building work had started, he wrote to Adam:

“I shall be glad you make out the plan of my grounds conform to the Lines you took… I wish to have it in my view to do it in the best manner.”

The influences behind Adam’s vision

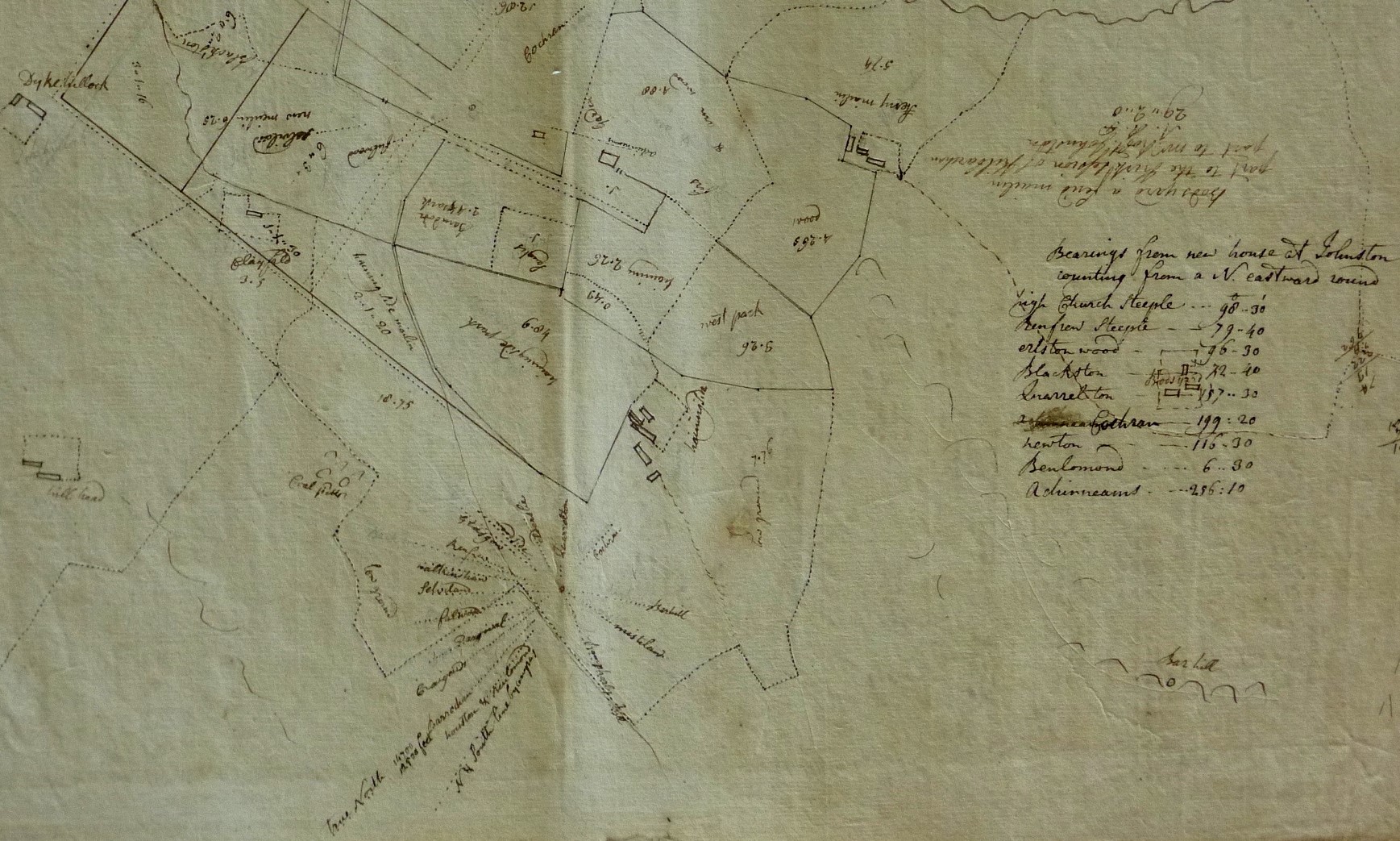

John Watt, detail from survey plan of Johnston Estate, Renfrewshire (c. 1729). The star at the bottom of the drawing shows the direction of various landmarks and the table on the right gives bearings from the house of the most prominent ones, including Glasgow High Church (cathedral) steeple, Renfrew steeple and Ben Lomond.

Boulton & Watt collection MS 3219. Reproduced with the permission of the Library of Birmingham.

Adam’s survey may have been similar to this one of an estate in Renfrewshire by John Watt. Watt used his paper very economically, squeezing in information and calculations wherever they would fit – even upside down. The survey not only shows features within the estate, but includes surrounding landmarks, showing their angle from the house. This would have helped establish the accuracy of the survey. It would have also influenced the layout of avenues and other linear features, as they are likely to have been lined up with the landmarks.

From page to landscape

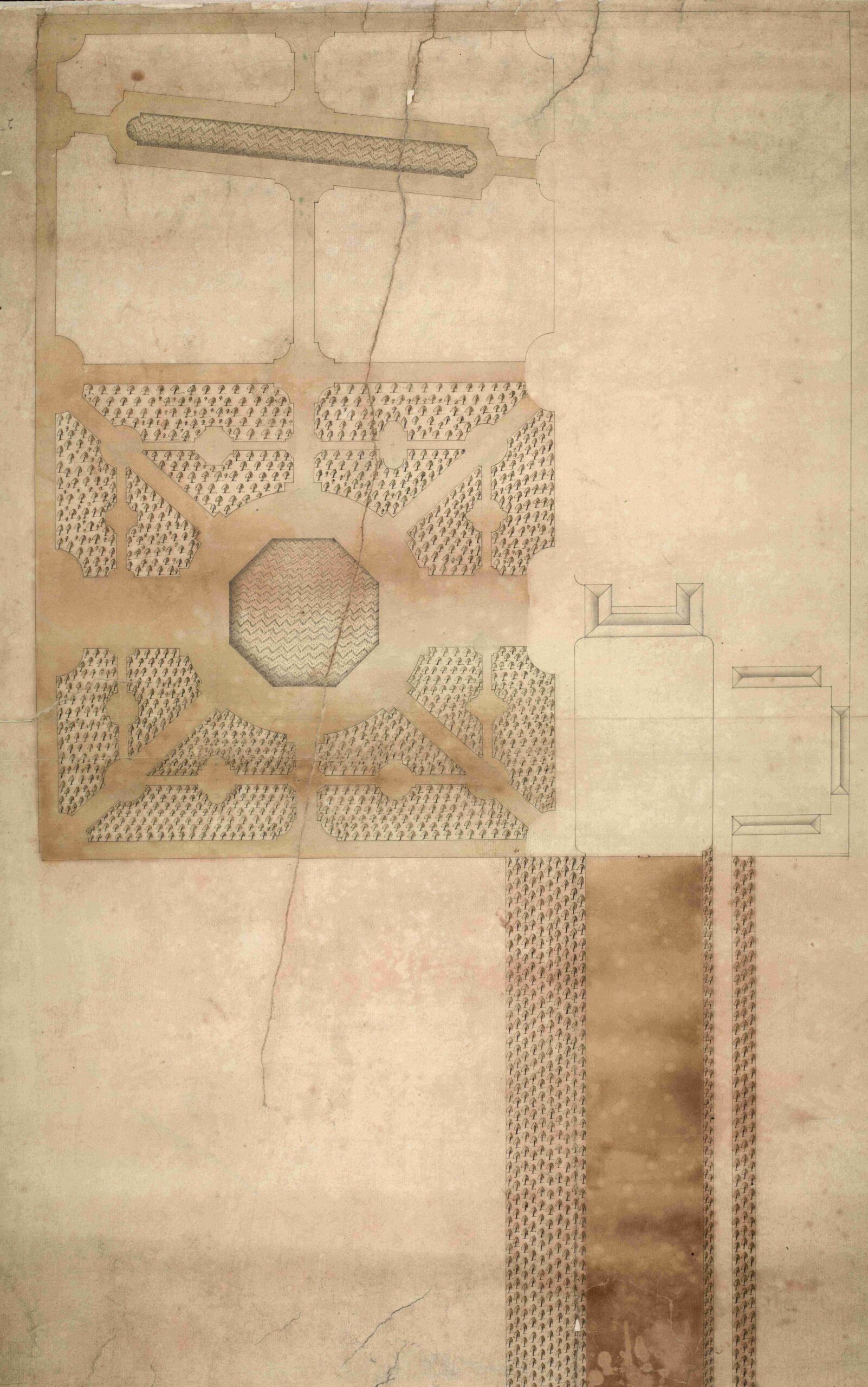

William Adam’s plan for La Manca, near Penicuik (1732). NRS RHP270/2. Crown Copyright.

This image shows a relatively small garden by Adam. The main feature is a square wood cut through by paths and a central octagonal pond. Every section of wood contains a glade or ‘garden room’, each of which is a different shape.

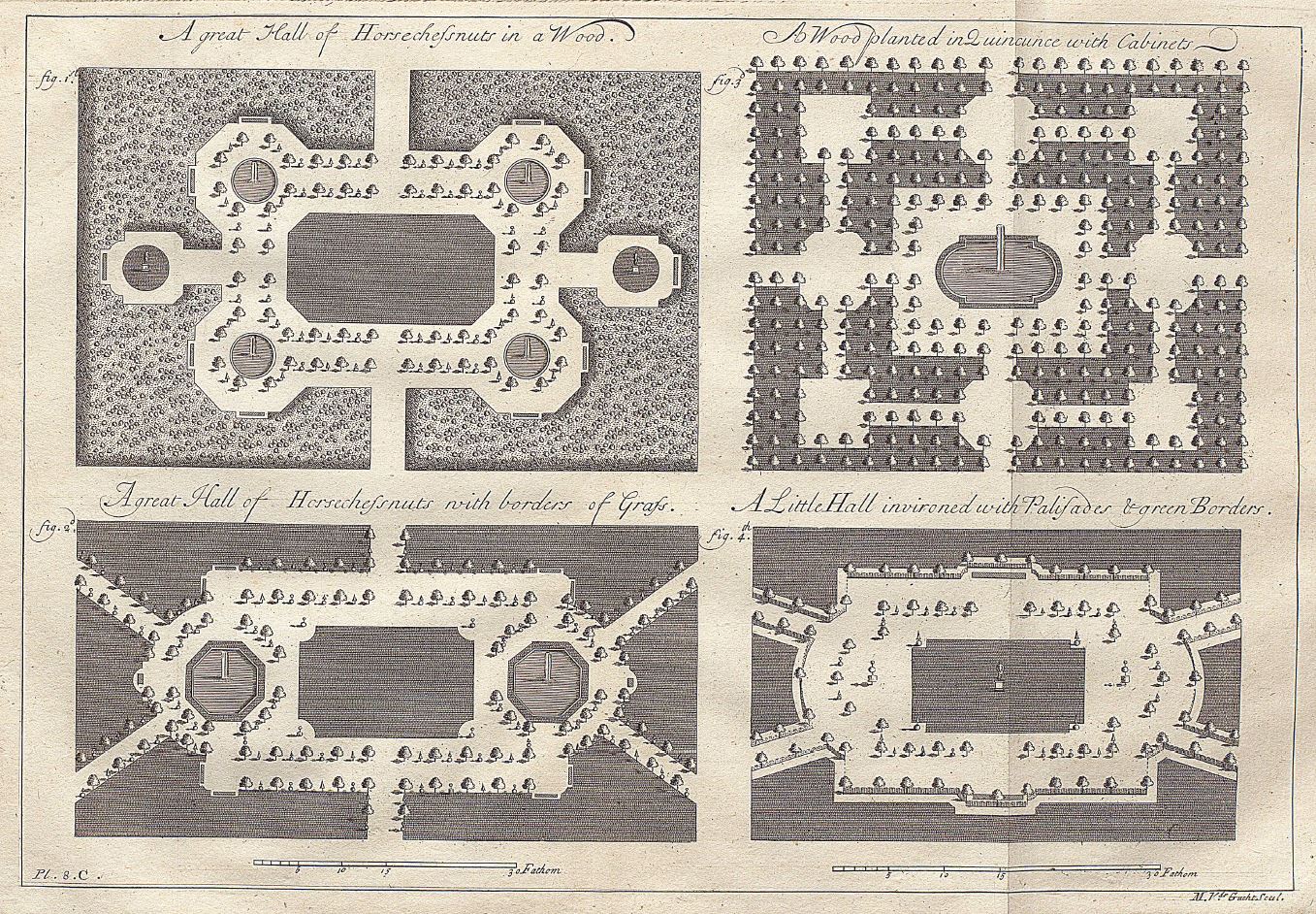

Dezalier D’Argenville, ‘Designs of Woods with Halls’ (image taken from John James’s English translation of 1712, which reused the original plates.) National Library of Scotland.

The Scottish Historical Landscape

Adam worked within an established Scottish method of garden planning that valued alignment and meaning.

Kinross House. Sir William Bruce’s groundbreaking Classical house is set in an axial garden that was aligned on Lochleven Castle as a sign of his allegiance to the Stuart royal family. NRHE SC 1690317 © Crown Copyright: HES. View on Trove.

Earlier Scottish gardens, like those at Kinross House, followed the principles introduced by Sir William Bruce. In the 1680s, Bruce bought an estate at Kinross and built himself a ground-breaking new house and garden. This was a key moment in Scottish landscape design as the house and grounds were firmly aligned on Lochleven Castle. Mary Queen of Scots had been imprisoned and escaped from Lochleven, and this alignment was a reference to Bruce’s allegiance to the Stuart cause.

Later gardens, particularly those by William Adam, tended to have multiple focus points, in contrast to Bruce’s single ones. Avenues and other linear features would be lined up with surrounding objects of cultural, historic or landmark importance. This was an important trend in Scottish landscape design that lasted through the first half of the 18th century. The term ‘Scottish Historical Landscape’ is now used to describe this type of landscape design.

What the Duff House garden was not

View across lake at Stourhead (Somerset) towards Temple of Flora, Temple Grotto, Bristol Market Cross, Stourton Church and Stone Bridge. Image credit: Louisa Humm.

I’ve shown you one of Adam’s garden plans, but what might his gardens have actually looked like? The above image shows Stourhead, one of the finest English landscape gardens. It was started in the late 1740s and gradually augmented over the next couple of decades. William Adam’s gardens did not look like this, and gardens like this barely existed during his lifetime. This type of landscape, inspired by the paintings of Claude Lorraine, with a profusion of garden buildings, naturalistic tree-planting, lakes and rolling turf, was yet to come.

Edzell Castle Garden. NRHE SC 674818 © Crown Copyright: HES. View on Trove.

Nor did Adam’s gardens look like this early 17th century formal Renaissance garden at Edzell Castle, Angus. Adam’s gardens tended to contain little by way of parterres, flower beds or topiary. Edzell’s garden walls form an important part of its design. By comparison, Adam only included walls where they were necessary for protecting a kitchen garden.

What might have been

Newliston

Central semi-circular pond at Newliston. The water is flat and still; a straight canal extends beyond it, separated by a weir-like cascade. To the right is one of a pair of grass mounds that form an amphitheatre. To the left a raised grass walkway is separated from the central field by a ha-ha. Image credit: Louisa Humm.

Newliston perimeter walk. The whole garden is encircled by a perimeter walk, about 1½ miles in length. The walk is bounded by a haha with ‘bastion’ projections at the corners and middle of each side. Dense planting of trees and hedges forms the inner edge, originally punctuated by openings for the vistas out of the garden. The views from the walk are therefore mainly over the surrounding farmland, rather than into the garden. Image credit: Louisa Humm.

Wildernesses

Wooded areas called wildernesses were cut through by straight or curving paths. These would have probably contained rough tree planting with undergrowth, bounded by hedges along the paths. The below image shows a ‘garden room’ with this type of planting. Additionally, some wildernesses might have been planted more formally with individual trees planted closely together at regular intervals, the spaces between them kept clear of undergrowth.

Dukes’ Square, Wrest Park, Bedfordshire. This is a wilderness garden room of the sort shown on the La Manca plan. Natural tree planting is enclosed by neatly-clipped hedges. The trees would, of course, have originally been much smaller. Image credit: Louisa Humm.

Hopetoun House

At about the same time that Adam designed the garden at Duff House, he was also working on improvements to the garden at Hopetoun House, originally designed by Sir William Bruce. Adam proposed a number of new features including waterworks, earthworks and a lot of buildings. It is quite likely that his design for Duff would have contained similar features.

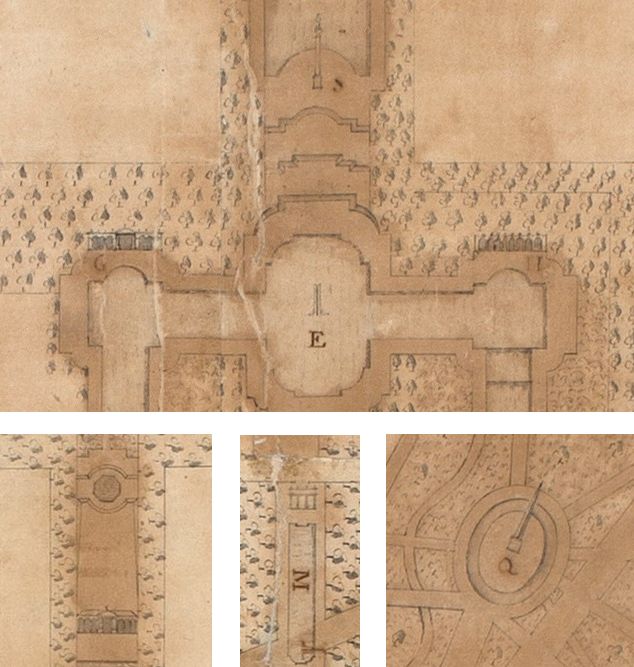

Details from A General Plan of Hopetoun Park and Gardens by William Adam (circa 1731-2). The top image shows the canal and cascades, two buildings, terraced earthworks, and a column to King George. Bottom right is an obelisk marking the site of Abercorn Castle. The other two images have been rotated. The left-hand one shows the bowling green and pavilion; the middle image shows a small canal and temple. Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the Hopetoun Papers Trust. Ref HHP 55.

Glimpses of the Duff House garden

The number of buildings designed by Adam for the gardens at Hopetoun is significant, as he may have intended a similar number of buildings at Duff House. Although almost no planting was carried out, Adam built three ornamental garden buildings in the grounds of Duff House. The two that survive are the only garden buildings by him still in existence. He also designed a mausoleum that, like the garden itself, was never to be.

The Temple of Venus

The Temple of Venus at Duff. William Adam, circa 1735. Image credit: Louisa Humm.

The Temple of Venus stands at the top of an open hill and is now a prominent landmark. However, to early 18th century taste, bare hill tops were generally considered ‘horrid’ and the decent thing was to clothe them in trees. It is likely that Adam intended this building to sit at the centre of a “belvidere”: a circular plantation of trees, with paths leading outwards like the spokes of a wheel. Each path would have framed a particular view or landmark in the surrounding landscape. Adam designed at least two other circular buildings within belvideres: one at Eglinton (Ayrshire) for Susannah, Lady Eglinton; the other at The Drum, near Edinburgh.

Avenue and belvidere at The Drum with central tower, probably designed by William Adam. The paths were aligned on landmark hills and islands in the Firth of Forth.

Detail from ‘Plan of lands and coalfield [of Drum]’. NRS RHP34652. Crown Copyright.

The Fishing Pavilion and Triumphal Arch

The Fishing Pavilion at Duff. William Adam, circa 1735. Banff Preservation and Heritage Society.

The fishing pavilion was a rather more sophisticated building, located on an island in the River Deveron. It is two storeys high. The lower storey may have contained a simple kitchen, while the upper floor would have been an elegant place to sit. A Triumphal Arch was also built on the island. This no longer exists and may have been made from timber.

Detail from General Roy’s Military Survey of Scotland showing the area around Duff House. “The Monument” is the Temple of Venus. NRHE DP571950 ©The British Library. Courtesy of HES.

This map from the 1750s shows dense tree planting on the island, split by a straight avenue. Intriguingly the avenue appears to align with the Temple of Venus, rather than the house. The pavilion’s door is also oriented to the temple. This detail shows how Adam choreographed movement and sightlines to key focal points, which did not necessarily always include the house.

The mausoleum that never was

William Duff, Lord Braco (created 1st Earl of Fife in 1759), painted by William Mossman in 1741. The pyramidal building to the right of his hand is possibly the mausoleum designed by William Adam. Reproduced with permission of His Grace The Duke of Fife.

We don’t know much about the Mausoleum, except that Braco paid Adam to design one. Unfortunately, Adam’s drawing doesn’t survive. However, Lord Braco’s 1741 portrait includes a pyramidal building at his elbow. This could well be his unbuilt mausoleum, its design influenced by the Pyramid of Caius Cestius in Rome.

The Duff House garden that never was

At Duff House, the scale of the commission and the lack of an existing garden may have given Adam freedom to innovate and adopt emerging fashions. The surviving buildings and the incorporation of the island suggest he was edging towards the English Landscape style, which was still in its early stages. Adam’s design might have been a Scottish landscape garden blending formal avenues with emerging English ideas of naturalistic design.

The absence of Adam’s garden invites us to imagine what could have been. Next time you visit Duff House, try a little time travel. Find an upstairs window with a view to the Temple of Venus. Picture a ring of planting around the hill, spokes of avenues pointing to churches and other hilltops. Perhaps you can also see open lawns, young trees, straight avenues, a calm pond and the glimpse of another temple…

This intended garden was once drawn in surveys, sketched in letters, but is now lost to time apart from its two surviving follies. It’s a compelling chapter in Scotland’s garden history precisely because it never quite happened.

Discover more about Scotland’s gardens

From Scotland’s Garden Secrets to Amazing Modern Landscapes, you can explore more Scottish garden history on our blog.

Sign up to our blog newsletter to get the latest stories straight to your inbox.