In Scotland, you are never more than 50 or so miles from the sea. It is unsurprising that we are therefore an inherently coastal nation, with over 10,000 km of coastline (if you include the near 800 islands) making up approximately 11 to 12% of the total European coastline. Today, the Scottish coast is home to over a million people and it is a significant natural and financial asset.

Rising Sea Levels and Coastal Pressure

Scotland has a varied coastline, ranging from low-lying, soft sandy beaches and dunes, through to towering hard-rock cliffs. This of course plays an important role in determining how the coastline responds to, for example, a passing winter storm or day to day tidal and wave action.

One of the most significant threats facing our coastline is from rising sea-levels. This can impact the coast in many ways through things like increased occurrence rates of flooding or changing patterns of erosion (and deposition). Coupled with onshore responses to climate change, this puts the coastline under increasing pressure.

Tantallon Castle – a formidable stronghold that stands on a hard-rock cliff overlooking the Firth of Forth

Sea-level rise specifically can be a complex subject to discuss, particularly in Scotland where, until recently, rising sea-levels were often offset or reduced by the legacy of extensive glaciation, in a process called Isostatic Rebound: During periods of glaciation, the immense weight of ice on the land’s surface causes it to deflect downwards. When this ice is removed, the surface ‘bounces’ back causing an apparent change in sea-level.

The last glacial maximum was experienced in Scotland around 20,000 years ago.

However, sea-level rise is now outpacing this process. This is due in part to rising global temperatures, which have caused increased melting of land-based ice and the thermal expansion of seawater.

In the past 100 years, data recorded by tide gauges across the globe have been showing yearly increases in sea-level of around 1.7 mm, with periods of much faster sea-level rise (up to 3.1 mm/year), especially in the last 20 years or so.

Projections of future sea-level rise, published by UKCP09, tell us that by the 2050s some parts of Scotland’s coast could see levels around 22 cm higher than they are now. That figure is based on a worst-case scenario outcome. This has clear implications with respect to coastal flooding and enhanced rates of erosion on susceptible coastlines.

What we are doing

Here at Historic Environment Scotland, we care for many sites situated in exposed coastal settings.

The Neolithic village of Skara Brae, Orkney, is perhaps one of our more famous coastal sites. At some 5,000 years old, it pre-dates the Egyptian Pyramids and Stonehenge and has been listed as part of a World Heritage Site since 1999.

House 1, Skara Brae

Ironically, Skara Brae was initially discovered due to successive storms, during the winter of 1850, uncovering the settlement from beneath the established dune system.

This is a familiar story across the country, where erosion of the coast continually uncovers new archaeological finds. Ultimately, the forces of nature cannot be beaten, so it is important that we record these finds where possible.

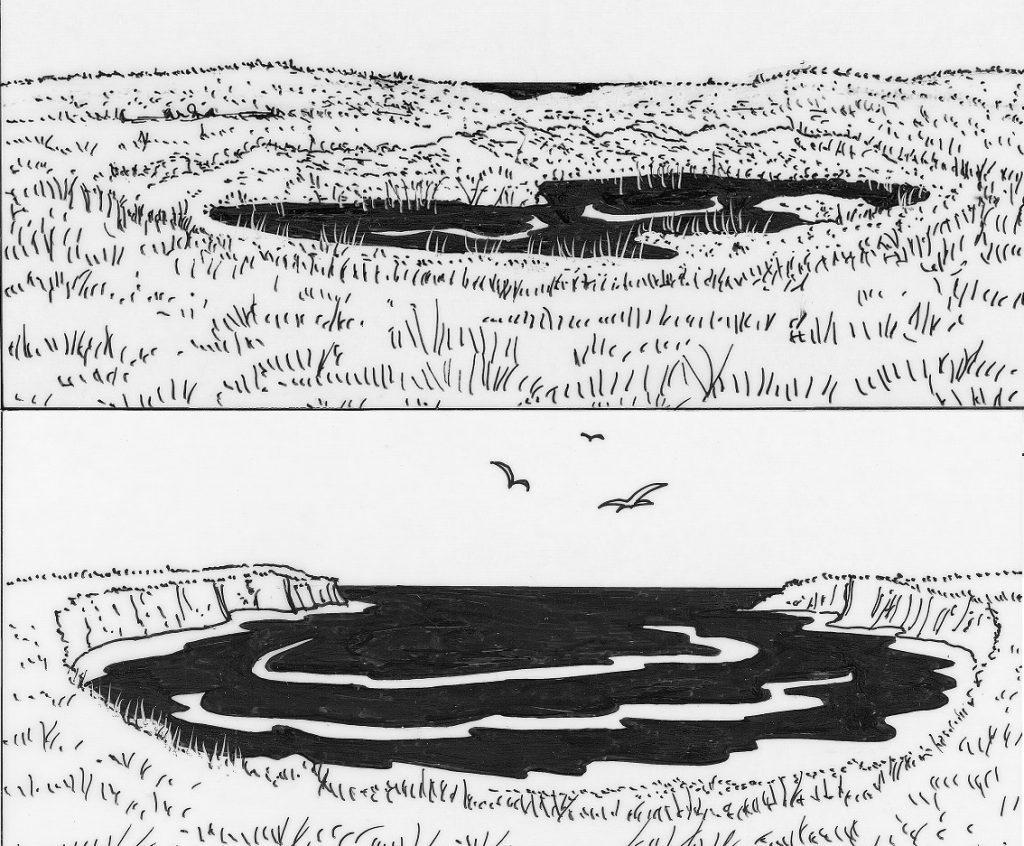

The freshwater loch on the Bay of Skaill before and after the cliffs were eroded and the loch drained into the sea.

Since 1996, we have funded Coastal Zone Assessment Surveys to quantify archaeological heritage at risk; you can see the sites on a map here.

Now, in a project co-funded by Historic Environment Scotland, you can volunteer as a ‘Citizen Archaeologist’ and help to monitor these sites or report newly discovered ones (details below). In a small number of instances, it has been possible to survey or excavate threatened sites and retrieve archaeological information before it is lost; examples include the ShoreDIG projects.

Another survey method, that can be used where appropriate is to create digital models by laser-scanning them. The Scottish Ten project has done just that at Skara Brae, meaning that important information relating to the site has been digitally preserved for future generations to interpret for themselves.

Scanning inside Skara Brae, Orkney, as part of The Scottish Ten – an ambitious five year project to use cutting edge technology to create exceptionally accurate digital models of Scotland’s five UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites and five international ones

Dynamic Coasts

Historic Environment Scotland is also part of the National Coastal Change Assessment (NCCA) steering committee, a project set up to collate information on coastal change, resilience and susceptibility to future coastal erosion. A key output from this project has been the on-going development of the Dynamic Coasts website – an interactive tool that will allow people to see how susceptible their coastline is to erosion. Tools like this will help us make more informed decisions, with respect to adapting to future coastal change.

Get Involved

You can help record Scotland’s archaeological past by downloading the Scotland’s Coastal Heritage at Risk ShoreUpdate app. This allows you to record and submit information about archaeological sites at risk from coastal erosion. This is a project part-funded by Historic Environment Scotland and run by SCAPE.