People have always made pilgrimages, and millions still do – to Lourdes, to Rome, or to the banks of the River Ganges; in smaller numbers to the birthplaces or homes of those they admire, to important battlefields, to places where something significant has happened. The pilgrim is a universal figure: the traveller with a purpose who sets out to find something that can only be found in some special place.

‘It is to Iona that people flock’

Iona, that small Hebridean island off the coast of Mull, is a place of pilgrimage – undoubtedly the most important such place in Scotland. There are other islands off the west coast of Scotland that are every bit as beautiful, there are other islands that have well-known historical and cultural associations – the island of Staffa, with Fingal’s Cave, is only a few nautical miles away – but it is to Iona that people flock.

Some of them may have only the vaguest idea of where Iona is and come because it is on an itinerary planned for them by a tour company; others may be interested in the island’s early Christian associations; some at least come because they believe they will be moved by the spirituality of a holy place. You can see this modern pilgrimage taking place. There are the tour buses crossing that winding road across Mull; there are the full car parks on the Mull side; there are the crowds on the small ferry plying its way across that shallow channel of green water that is the Sound of Iona.

It may surprise us that so many pilgrims still make the journey to Iona. In our secular societies, especially in those of Protestant background, we feel vaguely uncomfortable at the notion of the spiritual quest, and even more uncomfortable than that at the idea of the journey in search of a miracle. And yet these things have not faded away entirely; they still linger, surviving the triumph of science in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

‘This was a lawyer speaking under the rational sky of contemporary Sydney’

A year or two ago, when I was in Australia, I was invited to an event in a house on the Sydney waterfront. The event was in aid of a charity, and the house was a very luxurious one. Expensive works of art were everywhere and the small group of people there – mostly women, and mostly elegantly dressed – were clearly well-off and, in some cases, I imagined, rather influential.

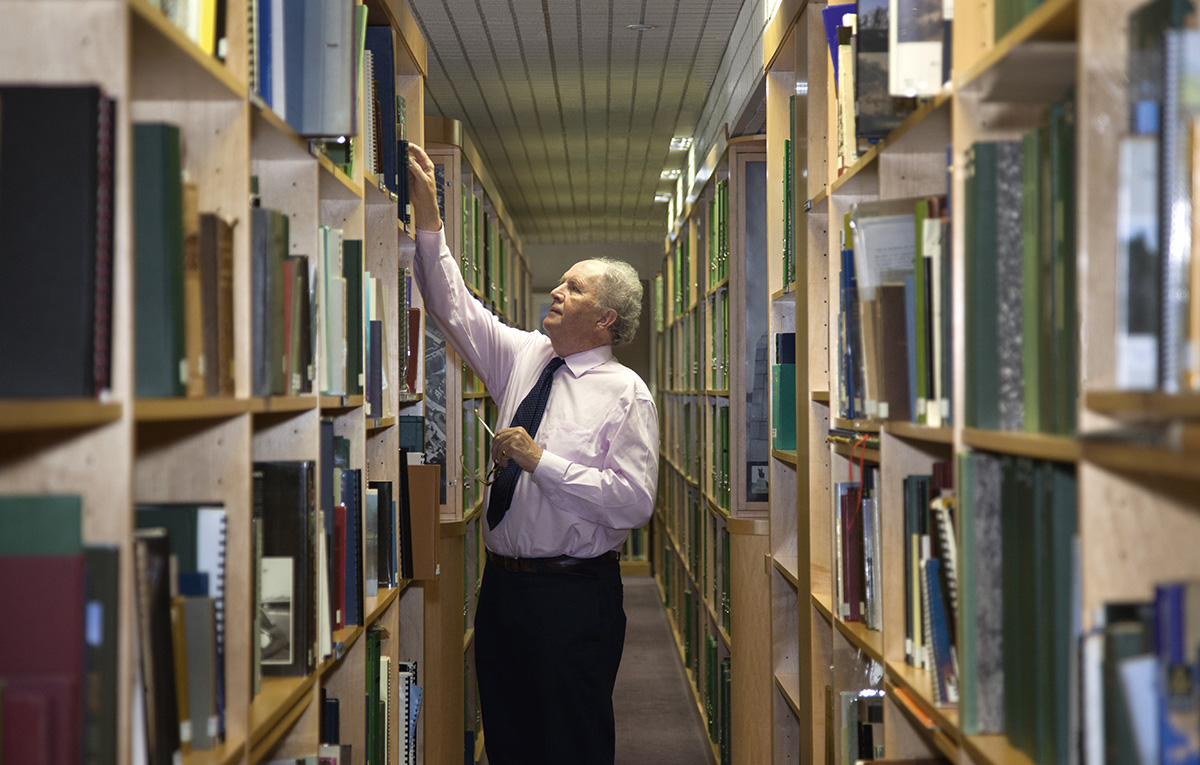

Alexander McCall Smith exploring the Historic Environment Scotland archives

A woman came up to me after the talk, when the guests were milling around having coffee. She introduced herself as a lawyer, and went on to tell me that she had recently been in Scotland. ‘I was not at all well,’ she said. ‘In fact, I was hopelessly ill with cancer. I had been given a short time to live; nothing could be done for me. And then …’

She paused. Those who have something to say that they know others will not believe often will look into your eyes to prepare themselves for mockery. She did this, and then continued, ‘And then I visited Iona. While I was there, I felt an extraordinary jolt. It was just like that – a jolt.’

I listened.

‘And then I came home and I was completely cured. The doctors could not believe what they saw. I was cured.’

This was not somebody from a Mediterranean culture of saints and miracles: this was a lawyer speaking under the rational sky of contemporary Sydney. She was convinced that what she experienced on Iona had been a miraculous cure. For my part, it seemed quite remarkable that we were having this conversation about a place of pilgrimage in Scotland, so distant, so different, so utterly unlike those Australian surroundings.

A large crowd of Victorian ‘pilgrims’ gathers outside the abbey in this photography from 1890

‘Holy places are made holy by men and women’

I find that I cannot believe in miracles. I suspect that behind every apparently miraculous event, there is a rational explanation compatible with the laws that science tells us govern our universe. But in my meeting with that woman I could not say to her that I simply did not believe her. I am sure that she was telling me the truth as she saw it; this had happened to her, and it had happened to her for reasons that might be difficult to explain. In her view, her visit to Iona somehow saved her life. Even if she simply experienced a spontaneous remission of her cancer that had nothing to do with where she was at the time, the fact remains that for that particular woman, her pilgrimage to Iona was the reason she was still there to tell me about it.

So it is, perhaps, that the reputation of places of pilgrimage is perpetuated: those who are affected by them speak of their experience to others, and slowly a place becomes invested with special standing. And perhaps it is the fact that so many believe that a piece of ground is hallowed that ultimately makes it such. Holy places are made holy by men and women. Years of human hope and human striving seem to linger in such places. Chants, songs, prayers, tears – all these form the weather there. The buildings of a holy place, a place of pilgrimage, will often express all these hopes, all this faith, all this human yearning.

This blog is an extract from the Historic Environment Scotland book ‘Who Built Scotland: 25 Journeys in Search of a Nation’, by Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Crawford, James Robertson and Kathleen Jamie. Whether visiting Shetland’s Mousa Broch at midsummer, joining the tourist bustle at Edinburgh Castle, scaling the Forth Bridge or staying in an off-the-grid eco-bothy on Eigg, the authors unravel the stories of the places, people and passions that have had an enduring impact on the landscape and character of Scotland. The book – which has just been named a Waterstone’s Scottish Book of the Month – is out now in paperback, priced £9.99.

Alexander McCall Smith is one of the world’s most prolific and popular authors. He has written over 80 books, including the No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series and the Scotland Street novels.