Margaret, Lady Moir was born in Gorgie, Edinburgh, but spent her formative years in the village of Dalmeny, close to where the Forth Bridge would be built. Her father, John Pennycook, was the quarrymaster at Dalmeny.

As work started on the Forth Bridge, William Arrol, in charge of construction, recognised the potential of a young engineer, Ernest Moir. At the age of just 22, Ernest became responsible for building one of the great cantilevers of this massive steel bridge.

A Forth Bridge romance

Queensferry Cantilever by Philip Phillips (Briggers Archive)

Born in England, with parents from Montrose, Ernest was one of the young bachelor engineers working on the Forth Bridge. The bachelors were keen to enjoy the local social life, and there were a number of Forth Bridge romances.

Ernest and Margaret married on 1 June, 1887. They met through Margaret’s frequent visits to the bridge’s caisson foundations. These giant cylinders on the river bed used compressed air to keep water out. Margaret had been greatly concerned about how the pressure caused the ‘bends’, a painful and debilitating condition.

Ernest was a rising star in the civil engineering profession. His next job took them to the Hudson River Tunnels project in New York, where compressed air was also used. Again, Margaret frequently visited her husband’s work. Working conditions were far worse than at the Forth Bridge. 25% of the workforce were dying every year due to the effects of compressed air.

Encouraged by Margaret, Ernest developed the world’s first Medical Air Lock to relieve the condition. This reduced the annual death toll to less than 2%. The air lock was widely adopted across the industry.

Ernest Moir (Briggers Archive)

Margaret accompanied her husband on his many projects in Britain, America, Chile and China. She was always involved in his work and saw first hand the achievements but also the dangers of civil engineering.

Margaret was the first woman to walk through the Blackwall Tunnel while it was being built (with air locks). She accompanied Ernest 750 miles into the Chinese interior when he worked on the Honan Railway, even though the Peking Legation had refused her permission to make the dangerous journey.

World War I

At the outbreak of WW1, the Moirs turned their attention to helping the war effort. Concerned about the long hours of the women munitions workers, Margaret organised a band of Women Relief Munition Workers.

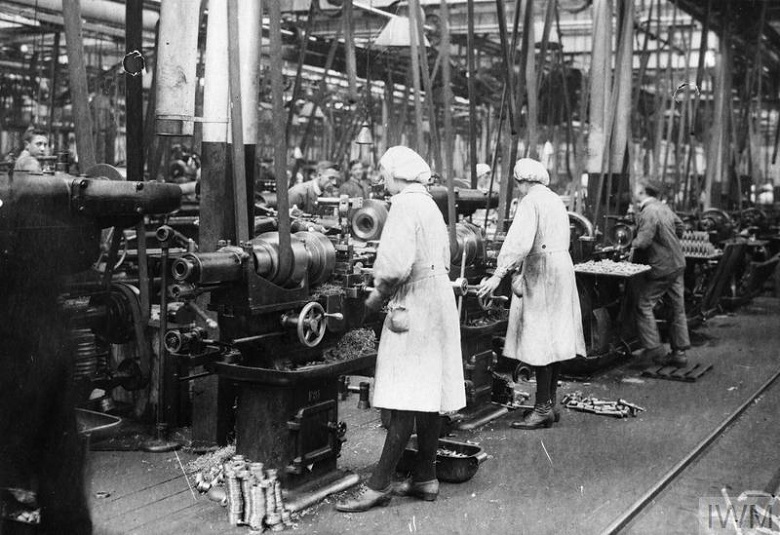

These ‘educated women of the leisured classes’ provided weekend relief for the exhausted women workforce. Margaret herself worked 18 months as a munitions lathe operator.

She was also treasurer and secretary of the Women’s Advisory Committee of the National War Savings Committee. She raised several hundred thousand pounds by organising the sale of war savings certificates and war bonds in London.

In recognition of her wartime work, Margaret was awarded an OBE. Ernest was made a baronet in recognition of his services to the Minister of Munitions.

Women munition workers at their lathes (© IWM – Q 108394)

The war created many work opportunities for women who replaced men sent to the font. However, after the war, all that changed.

Although the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 made it illegal to exclude women from jobs because of their gender, the 1919 Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act forced most women to relinquish their wartime roles as the men came home.

Many women with engineering training and experience were forced back to lower paid, domestic servant roles and menial work.

The Women’s Engineering Society

The war had demonstrated that women worked very successfully in engineering roles. But there were few peacetime opportunities for them to develop a career. Margaret realised that courses for women to train as engineers had to be created.

The Women’s Engineering Society (WES) was founded in 1919 by a small group of influential women, including, as she now was, Lady Moir. She and other members of the WES worked tirelessly to set up training courses for women engineers and encourage women to take up engineering as a career.

Margaret also recognised the difficulty women had with the time-consuming drudgery of domestic chores, limiting career opportunities. Realising the great advantages electric appliances could bring, she became an early member of the Electrical Association for Women (and went on to become its president). The association trained women in the theory, use and promotion of electrical labour saving devices in the 1930s.

Margaret, Lady Moir (IET Archives)

Margaret was involved in many other activities to support working women including hospitality for visiting professional women; the Over-30 Housing Association, and sponsoring an all-electric flat for single women. She also held inspiring talks for women at her own home. One speaker was the record breaking pilot, Amy Johnson.

As president of the WES, Margaret concluded in her 1928 inaugural speech,

It is now relatively simple for the girl to go through the technical school or college education, and with her wits as bright as any man, obtain a degree in Engineering.”

Margaret died in 1942, at the age of 78. The work of the Women’s Engineering Society continues to this day.

Frank Hay is a member of The Briggers, a Forth Bridge research group based in South Queensferry. The Briggers give talks and work with Historic Environment Scotland, Transport Scotland, Network Rail, and Barnardo’s on Forth Bridge projects.