Modern times see us finding more environmentally friendly and sustainable ways to eat. But are we just following in the footsteps of the monks who lived in Scotland almost a thousand years ago?

In National Vegetarian Week, HES Sustainability Officer Louise Kelly takes us on a monastic journey through medieval Scotland, exploring the role of food in a monk’s life and discovering how abstaining from eating meat is far from a modern idea.

The Rule of St Benedict

A priory at Dunfermline Abbey was founded by St Margaret in 1070

Monks at Benedictine abbeys like Dunfermline and Iona followed the Rule of Saint Benedict. This book of commandments written in 516 by Benedict of Nursia contains numerous food-related rules, including limiting meat consumption.

Chapters 39 and 40 of the book dictate that monks may enjoy two meals a day, with two cooked dishes at each. Each monk is allowed a pound of bread, along with a quarter litre of wine.

Benedictine monks were not quite vegetarian by modern standards, though. Eating meat from four-legged animals was prohibited, but they could eat meat from birds and fish.

An artist’s impression of how the kitchens and dining areas might have looked at Dunfermline Abbey around 1400

Artisan bread for the Abbot

Cheap, easy to produce and filling, bread was key part of most people during medieval times, monks included.

But not all bread was created equal. The grains used to make bread would vary depending upon the status of the individual it was produced for. It was not uncommon for senior members of the religious community such as the Abbot to eat higher quality, more expensive bread.

This bread was usually made from finer, more processed flour. It was shaped into smaller loaves, usually for consumption by just one person. As far as we can tell these would be somewhat similar to a modern white dinner roll.

Senior members of the religious community and their guests would often eat higher quality food

Cultivating Cistercians

The Cistercian Order established their first Scottish monastery at Melrose Abbey in 1136. The Cistercians also followed the Rule of St Benedict – but used a stricter version than the Benedictines.

They were largely vegetarian and ate mostly plant-based foods. Exceptions were only made for the sick, who were given meat, or on feast days, when fish and eggs might be eaten.

Melrose Abbey from above

Working was key to the Cistercian way of life. Monks and lay brothers at Scottish Cistercian abbeys such as Glenluce, Dundrennan, Deer and Sweetheart would have grown food at or near their abbey. Typical foods grown in Scotland in the medieval period would have included cabbage, turnips, carrots, peas, onions and beans.

Herbs were also important both for culinary as well as medicinal uses. In contrast, many spices, including pepper, were not permitted as they were expensive and considered a luxury due to being transported long distances.

Sweetheart Abbey was the last Cistercian abbey to be established in Scotland

Standing at the heart of a fertile valley, Melrose Abbey quickly became one of the wealthiest foundations in the country.

Walter Bower’s great chronicle of Scottish history, the Scotichronicon, recounts how the local community relied on the Abbey for food during times of hardship:

‘When the calamity of a deadly famine threatened, a vast crowd of destitute people reckoned to number four thousand gathered at Melrose, and erected huts and tents for themselves in the fields and woods around the monastery for a distance of two miles.’

Accidental Vegetarians?

Common thinking in medieval times was that humans were entitled to make use of all resources available to them so voluntarily abstaining from meat was not common.

But even outside of monasteries, the church limited the eating of meat. Many days of the year were fast days, where meat was not permitted. The exact rules varied, often permitting the eating of fish and birds.

A typical meal at Melrose Abbey

Common dishes were variable and would have been made from what was available in the area at the time of year.

Pottage, for example, was eaten by almost everyone in the medieval period. Similar to a soup or stew, it usually contained vegetables and grains. There was sometimes meat, but only if it was available.

The result was that many medieval people, both in and out of religious orders, didn’t eat meat every day.

A return to the monks’ diet?

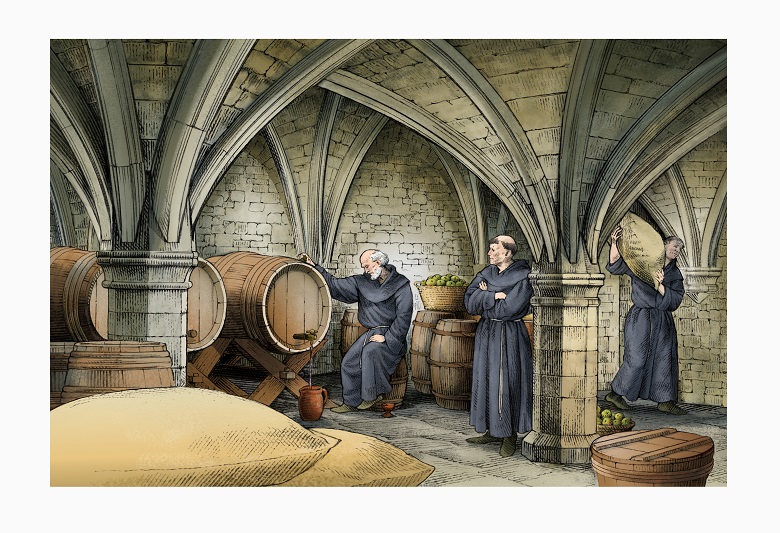

Benedictine monks working in the cellar, Dunfermline Abbey

While today’s vegetarian communities are often motivated by concerns about climate change with animal agriculture responsible for approximately 14.5% of global emissions, the Rule of St Benedict set a trend by abstaining from meat.

Scottish monks and the communities they supported weren’t vegetarian for the same reasons, but perhaps modern day veggies are inadvertently following in their medieval footsteps.

If you’ve been inspired to make some changes since the recent declaration of a Climate Emergency eating less meat is a great place to start. Could you be inspired by medieval monks to try going vegetarian in vegetarian week?

Head to our Climate Change webpages to find out how climate change affects the historic environment and what HES are doing to help limit the impact.