Can you imagine a different Scotland, a Scotland where women are commemorated in statues and streets and buildings?

Where Are the Women? by Sara Sheridan is a guidebook to that alternative nation. In the book, adapted or imagined monuments are dedicated to real women, telling their often unknown stories.

In these extracts from the book you can discover four of those women, together with their imagined memorials.

Susan Ferrier (Edinburgh)

Edinburgh’s Waverley Station and Scott Monument are re-imagined as commemorating author Susan Ferrier in Where Are the Women?

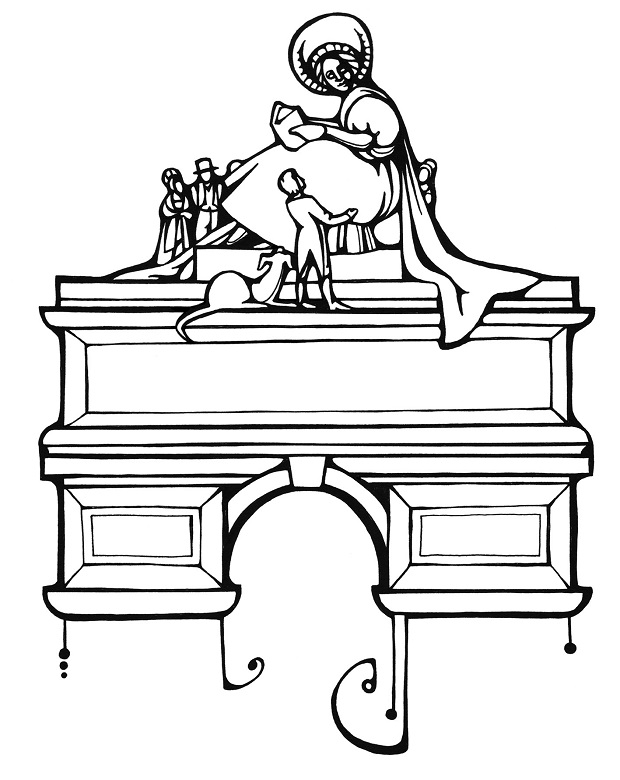

The Ferrier Arch is the world’s largest monument to a writer. Designed as a triumphal arch festooned with wrought iron figures, it is dedicated to Susan Ferrier (1782–1854).

In 1809, Ferrier began planning a novel with a friend. However, apart from one chapter, she wrote Marriage alone and it was published anonymously in 1818. The novel was hugely successful.

Marriage was attributed by many to Sir Walter Scott, who publicly praised his ‘sister shadow’ and called the book a ‘very lively work’.

Ferrier’s other novels, The Inheritance and Destiny were both critical and commercial successes. Marriage was sold for £1,000 (more than Jane Austen received for any of her novels). Ferrier became friends with many literary worthies of the day.

As well as a large effigy of Ferrier herself, the regal arch is festooned with statues of her much-loved characters (some of whom spoke in Scots and in Gaelic). If you look closely, you will spot a representation of the great woman’s supporter Sir Walter Scott with his deerhound, Maida, at Susan Ferrier’s feet.

An aerial view of Waverley railway station and the Scott Monument from 1929. Both have been re-imagined by Sara Sheridan

Edinburgh’s main railway station nearby is somewhat dramatically known as Destiny Station after Ferrier’s last novel, prompting a thousand jokes about ‘getting off the train at your destiny’.

Christian Shaw (Glasgow)

On Clydeside, Sheridan imagines a moving memorial to an industrial pioneer.

On a path by the Clyde you will find out about Christian Shaw (1684–1750), who introduced the threadmaking industry to Paisley. There is a kinetic installation here of a spinning spool that commemorates her commercial success.

The thread industry in the town would go on to employ seven times more women than men. The word ‘spinster’ was coined to describe the unmarried women who worked as spinners. They had to leave their job if they married.

Archive image from 1972 of part of the Glasgow, Paisley & Johnstone Canal, running through the Ferguslie Mills of J & P Coats. Christian Shaw was instrumental in bringing the thread industry to Paisley, which has shaped much of the town’s history.

There is also a darker aspect to Christian’s life. At the age of 11, she gave evidence that led to eight people being accused of witchcraft in the Bargarran witch trials. All eight were killed.

There is a red thread running through the otherwise white memorial to mark this time in her early life.

Mary Somerville (Southern Scotland)

In the Border town of Jedburgh the book envisages the Somerville Museum.

It is dedicated to the life and work of Mary Somerville (1780–1872). Somerville was a science writer, polymath and campaigner for women’s rights.

Born in the town this ‘Rose of Jedburgh’ was ‘the Queen of 19th century science’. Her works formed the backbone of the first science curriculum at Cambridge University. She was the joint first female member of the Royal Astronomical Society (alongside Caroline Herschel).

Mary Somerville by Evert Duykinck (Public domain)

A lifelong liberal, as a child she refused to take sugar in her tea as a protest against slavery. In 1868 she was the first person to sign John Stuart Mills’s unsuccessful petition for the female suffrage.

In un-imagined Britain, Somerville is already commemorated on both sides of the border.

Somerville College, Oxford, is named after her, as is a committee room at the Scottish Parliament. She also appears on the Royal Bank of Scotland £10 note. You can see the house she grew up in on Somerville Square in Burntisland, Fife (the street having been named after her).

A perspective sketch from the HES Canmore archive of a 1958 proposal to redevelop Somerville Street and Square in Burntisland.

Ragnhild Simunsdatter (Shetland)

Sheridan has conceived a maritime monument for a significant medieval woman in the far north of Scotland.

Near the lighthouse on Papa Stour look out for the wooden Skeleton Ship on the rocks with a female figurehead. It represents Ragnhild Simunsdatter (1250–1300), who, in 1299, stood up to powerful authority figures in a medieval land dispute.

The only record of her life is in legal documentation, so information about her is scanty. Nevertheless, it is possible to form an impression of her personality.

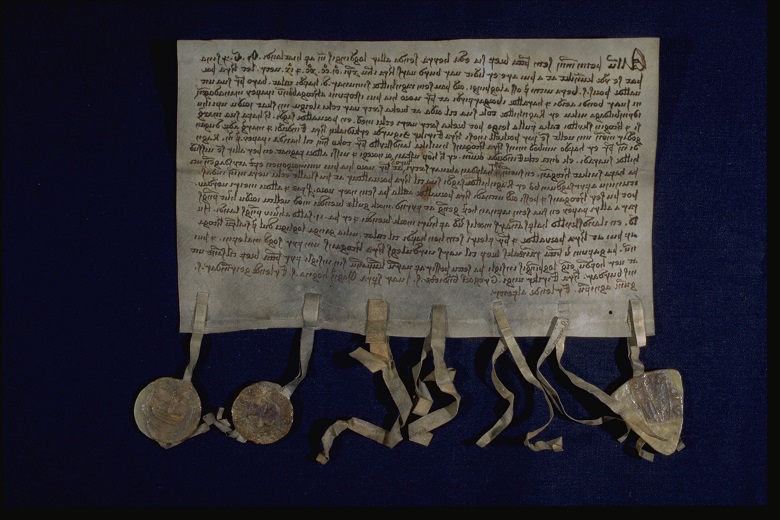

A letter drawn up by the Lawthingmen of Shetland and addressed to Duke Hakon Magnusson, tells us that Lord Thorvald Thoresson has been accused of financial improprieties regarding the collection of rents in Papa Stour, and that he was concerned to clear his name.

The accuser is Ragnhild Simunsdatter, a tenant of Papa Stour.

Image © Shetland Museum & Archives. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Image © Shetland Museum & Archives. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Making such accusations was brave and Ragnhild seems to have prompted a full enquiry. It is because of this document that historians understand the land use, rents and values of Papa Stour in the 13th century.

But the significance of Ragnhild’s intervention goes far wider. Because of ongoing issues relating to land ownership, the Skeleton Ship has become an emblem used by groups across Scotland campaigning for land reform. The monument was designed to erode over the years – becoming increasingly ghostly over time.

More monuments?

Find out about many more remarkable women and re-imagined historical environments in Where Are the Women?: A Guide to an Imagined Scotland by Sara Sheridan, published by Historic Environment Scotland.