Scotland’s shores might seem a far cry from the Pirates of the Caribbean, but as an island nation, Scotland has encountered its fair share of salty seadogs.

Here are some lesser-known tales of marine marauders to shiver your timbers.

Privateer or pirate?

Back in 1627, Andrew Bruce from Shetland was left destitute after pirates attacked Muness Castle.

The raid on Scotland’s most northerly castle happened on a summer’s day in August. We can only imagine what the inhabitants of Unst thought when Privateers from Dunkirk came ashore. Unfortunately, records from the time don’t give us any clues as to why the privateers singled out Muness Castle. There were international shipping routes around Shetland and rich fishing grounds which may have drawn the privateers to Shetland in search of ships to capture and plunder. Perhaps Andrew’s castle looked like easy pickings to these buccaneers?

A reconstruction drawing showing how the hall at Muness Castle might have looked in its heyday.

The privateers were acting on behalf of the Spanish Empire. Their aim was to cause as much chaos as possible to the merchant shipping of their enemies during the time of the Dutch Revolt (1568–1648). These raiders were officially sanctioned by the Spanish government to carry out attacks. However, in 1587 the Dutch declared the Dunkirk privateers “pirates”.

A sorry state

The looting of Muness Castle had a lasting impact on the fortunes of Andrew Bruce. In 1631, The Register of the Privy Council of Scotland records an appeal from Bruce. He humbly begs for more time to repay the debts that he ran up after the “unhappie burning of his house of Mones”.

The register reveals that:

“He sincerely intended to repay the same as soon as he could get his land plenished, but his rigorous creditors, impatient of any delay, threaten him with captions and other legal procedure. He therefore craves their Lordships’ protection till Lammas next that he may take order with his creditors.”

The Lords did grant Andrew Bruce an extension. However, in spite of their compassion, it seems that the Bruce family fortunes did not revive.

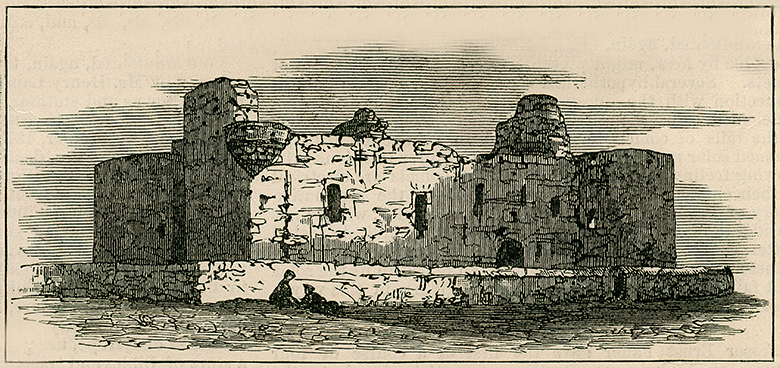

The ruins of Muness Castle in Unst.

Muness Castle was sold by the Bruce family in 1718. An inventory taken at the time makes for sorry reading. It lists a parcel of old pewter, one old small kettle, a parcel of old leather and timber chairs.

Slave to sultana

In 1769, the actions of pirates had an astonishing impact on the life of one young Perthshire woman.

Helen Gloag was the daughter of a blacksmith. It seems her childhood in the small village of Muthill was an unhappy one. Her mother died when she was young and her father remarried. It is thought that her stepmother was abusive towards her.

By the time she was 19, Helen was so desperate to leave her life in rural Scotland that she signed up to emigrate to South Carolina as an indentured servant. Along with a group of friends, she set sail from Greenock in May 1769.

A view of the port of Greenock from 1786.

Two weeks into the voyage, off the coast of Spain, their ship was raided by Barbary pirates. These attackers hailed from the north coast of Africa. The main purpose of their attacks was to capture slaves for the Ottoman slave trade as well as the general Arab slavery market in North Africa and the Middle East. The future looked very bleak for Helen.

An unexpected twist

The pirates took Helen to the slave market in Algiers. Here she was bought by a wealthy Moroccan who then gifted her to Sultan Sidi Mohammid ibn Abdullah. With red hair and green eyes, it seems Helen was a striking looking woman. The sultan added her to his harem. Over time she became his wife and was given the title of Empress.

Although it’s impossible to know for sure what her relationship was like with the sultan, we can guess that he afforded her some privileges. The only reason we know her story is that she was able to write home and invite her brother to visit her in Morocco.

Sadly, it’s likely that Helen’s life was cut short violently. When the sultan died in 1790, his son Yazid inherited the throne. Helen was replaced as Empress. In an effort to consolidate his power, Yazid killed Helen’s two sons and it is probable that Helen was executed too.

The reluctant pirate

“I do solemnly declare as a dying man, that whatever I did while I was aboard of the pirate ship, was by force, and upon peril of my life.”

This quote is taken from the last speech and dying words of John Stewart. Stewart was executed in Leith on 4 January 1721 for the crime of piracy and robbery.

This, apparently reluctant, pirate was one of 21 men captured in Argyll in 1720. The suspicious bunch were intercepted while abandoning their ship, The Eagle. The local laird, Campbell of Stonefield, boarded the ship to inspect it. He was amazed by what he found: a hold full of gold!

The ragtag bunch were taken to Edinburgh where they were imprisoned at Edinburgh Castle. Their trial lasted six months. It was a complicated case.

The steps leading down into the prison vaults at Edinburgh castle.

Stewart’s testimony paints a picture of grave misfortune. He explains that he left Dartmouth on a merchant ship bound for the East Indies in March 1719. Upon reaching the coast of Guinea, their ship was seized by the Welsh pirate Howell Davis.

“After we had made what resistance we could, they compelled me and several others out of our ship to go along with them; and upon our refusal threatened to put us immediately to death, or leave us upon some desolate island, which is nothing better than death.”

He then went on to swear that: “during the time we was aboard of them, I never seed them wrong man, woman or child.”

A grisly end

Most of the men, like John Stewart, claimed that they had been forced into a life of piracy. Only two of the gang admitted their guilt. Nineteen men went to trial. Seven were set free and the remaining dozen, including John Stewart, were found guilty.

Robert Hews and John Clark, who had admitted their guilt, were taken to Leith Sands and ‘hanged by the neck upon the gibbet’ on 14 December 1720. Their bodies were left hanging in chains between the high and low water mark as a warning to others.

The dozen men who had been found guilty at trial were hanged in early January 1721, proclaiming their innocence until the very last.