In 1504, two young African girls referred to as ‘Moorish lassies’ arrived at Edinburgh Castle. Acting as ladies-in-waiting to the Lady Margaret, the king’s daughter, they soon found themselves at the heart of elite Scottish society.

500 years later, a new Historic Environment Scotland research report has delved into records of their life at the castle. They feature details of fashionable clothing, lavish gifts and exclusive courtly activities.

The findings tell an intriguing tale of these remarkable women who became an important, if unexpected, part of the royal court in the early sixteenth century.

The Lady Margaret

We suspect from the references to the girls as ‘Moorish lassies’, they were likely Muslim and possibly travelled from their homes in North Africa.

Their stories became closely intertwined with another young woman of unusual status. Known simply as ‘the Lady Margaret’, she was an illegitimate daughter of James IV.

Her mother was Margaret Drummond, one of James’ mistresses. She was rumoured to have been secretly married to the King before she died in curious circumstances around 1502.

James IV favoured Margaret above his other children. Image: National Gallery of Scotland (Public domain)

This could explain why their daughter Lady Margaret was given far more attention and acknowledgement than James’ other illegitimate children.

They were given non-royal titles and sent away to be cared for by tutors. Margaret, on the other hand, had the title of a royal princess. She was present in court from childhood until marriage.

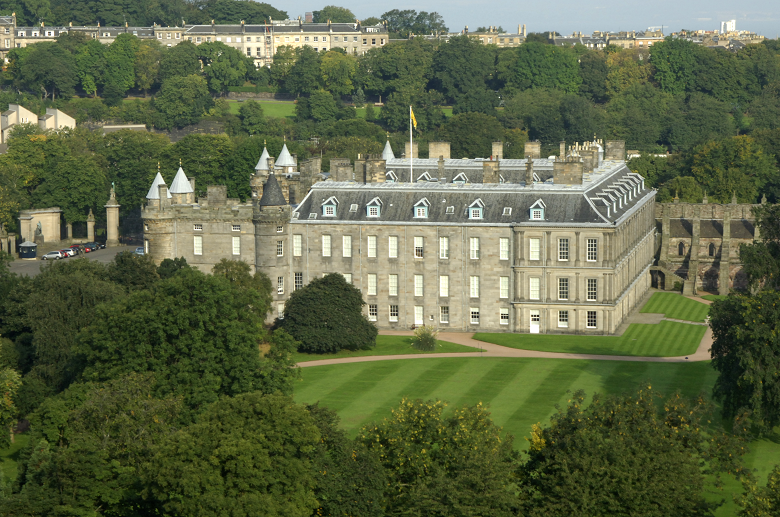

In the summer of 1503, James moved to Holyrood Palace. Margaret became head of her own household in Edinburgh Castle. It was to this household that the ‘Moorish lassies’ were welcomed. They became known as Ellen and (confusingly enough) Margaret. Sadly, but not unsurprisingly, the names they arrived in Scotland with were not recorded in the history books.

A Fashionable Court

The Lady Margaret’s household was a prestigious place. And in the ‘Moorish lassies’ she boasted a prime ‘status symbol’.

It was highly fashionable in Spain, Portugal and Italy for women of a princely rank to have African girls as attendants. Adopting this custom in Edinburgh added exotic flair to the court, subtly emphasising the status of the Stewart royal family.

The exact location of the lodgings of the ‘Lassies’ is unknown. Possibilities include the Kings Chamber built by James I and a tower on the south flank of the castle

That some Renaissance rulers regarded young Africans like the ‘Moorish lassies’ as status symbols to be bought and sold or given as gifts strikes a very unsettling note. It is possible that Edinburgh’s ‘Moorish lassies’ were liberated from slavery before coming to Scotland and the records indicate that the lives they lived in Scotland were as free people. But the experience for any children finding themselves so far from their homes in the early 1500s would have been a scary one.

What we know for sure is that both ‘Moorish lassies’ were quickly involved in courtly life as respected ladies-in-waiting to the Lady Margaret. All three were probably about ten years old.

Tours and Tournaments

The annual expenses of Lady Margaret’s household were £100, equivalent to the salary of a senior courtier.

They covered dancing lessons by a French drummer called Guillaume, along with sewing classes by Janet Turing, the same seamstress who made the king’s underwear.

The girls also learnt to ride horses. We know that the Lady Margaret was capable of “a long ride on a bad road in winter,” probably accompanied by her ladies-in-waiting.

Margaret and the ‘Moorish Lassies’ were competent horse riders, and may have been involved in theatrical tournaments

The trio appeared at courtly events, including a royal tour of the Borders in December 1504. They would also have encountered the king at annual chapel services celebrating the name day of the two Margarets.

It’s even possible that the ‘Moorish lassies’ played a central part in theatrical tournaments hosted by James IV in 1507 and 1508. The king played the role of “the Wild Knight” who battled other participants to win the hand of “the Black Lady,” perhaps played by the Lady Margaret and the ‘lassies’.

Robes Fit for Royalty

The best evidence of the fashionable life led by Margaret and the ‘Moorish lassies’ are the records of their lavish clothing.

Margaret’s wardrobe was certainly fit for a princess. A costume gifted to her in 1504 featured an ermine trim usually reserved for royalty. Other dresses were made from fashionable black velvet, offset by a necklace of 22 gold beads.

The ‘Moorish lassies’ wore more practical but equally fashionable attire. This included gowns of russet-coloured cloth and red petticoats, along with “double-soled shoes.”

Each of the girls received several pairs of new shoes every year. Margaret’s collection included “pantounis” and “caffunzeis” – velvet-covered sandals and Italian-style dancing shoes.

At Home in Edinburgh

In 1510, the Lady Margaret was married to Lord Gordon. Heir to the Earl of Huntly, he was probably the most eligible bachelor in Scotland.

Aerial view of Garth Castle, part of the Lady Margaret’s land after her marriage

Though her marriage took her north to Gordon’s vast Highland lordship, she was a frequent visitor to the royal court. She and her husband had their own room at Holyrood Palace.

Margaret didn’t lose her taste for fashionable clothes. She continued to buy copious amounts of shoes in Edinburgh. For Christmas 1511, she was given a gown worth a staggering £100.

Nor had she lost her riding skills, having “rode home by mountain roads” after a visit in November 1512.

The Lady Margaret was a regular visitor to Holyrood Palace

Generous gifts – and a marriage?

Records tell us that Ellen stayed in Edinburgh, transferring to the royal household. She was probably the “black maiden” mentioned in 1512 as an attendant to the queen.

Margaret almost disappears from the records until 1513, but the ‘lassies’ seem to have been reunited around Christmas. “The two black ladies” were given a joint New Year present of ten gold coins.

On St Margaret’s Day that year a “black Margaret” was gifted a new gown, creating a tantalising potential connection with an attendant called Margaret Prestoun who had ridden north with the Lady Margaret in November 1512.

Margaret Prestoun is recorded elsewhere as having received a gown at the same time as “black Margaret.” Could they be one and the same? If so, the surname “Prestoun” suggests that one of our ‘Moorish lassies’ married a Scotsman.

The Lady Margaret and the ‘Moorish Lassies’ attended annual St Margaret’s Day services in St Margaret’s Chapel, the oldest building in Edinburgh

Remembering the ‘Moorish Lassies’

The Lady Margaret was widowed in 1517. Though she re-married to Sir John Drummond of Innerpeffray, she continued to act at matriarch for Sir Gordon’s family. She became a great Highland landowner and occupied a prominent position in Mary of Guise’s royal court in the 1550s.

The trail for the ‘Moorish lassies’ goes cold after 1513, but Ellen and Margaret remain a fine example of the high-profile black immigrants that were present in Scotland in the early sixteenth century.

Their arrival in Edinburgh may have been motivated by James IV’s desire to show off his daughter’s social status, but they became successful and respected members of the court in their own right.

Their Edinburgh lifestyle in the company of the Lady Margaret is a fascinating episode in Scotland’s Black History.

You can discover more hidden histories of Edinburgh Castle by downloading Historic Environment Scotland’s research reports.

Want to discover more this Black History Month? Read the remarkable story of Tom Jenkins in The Smiddy and the School Teacher.