This Women’s History Month, we remember those executed for witchcraft in early modern Scotland. Between 1550 and 1700 nearly 4,000 people were accused, 85% of them women. A third to a half of those accused were executed.

The Church of Scotland heavily influenced witch hunts, seeing witchcraft as a sin and a threat to Christianity. Suspects would be imprisoned and interrogated with the aim of obtaining confessions, sometimes tortured with sleep deprivation.

During the panic of 1649-50 over 600 people were accused of witchcraft across southern and eastern Scotland. Six of those were from the parish of Dirleton in East Lothian.

Agnes Clarkson

In June 1649 the widow Agnes Clarkson confessed to witchcraft after being held prisoner in Dirleton Castle. It’s likely she was held in the castle’s pit prison. She was interrogated by a presbytery, or church court, including Johne Makghie, minister of Dirleton.

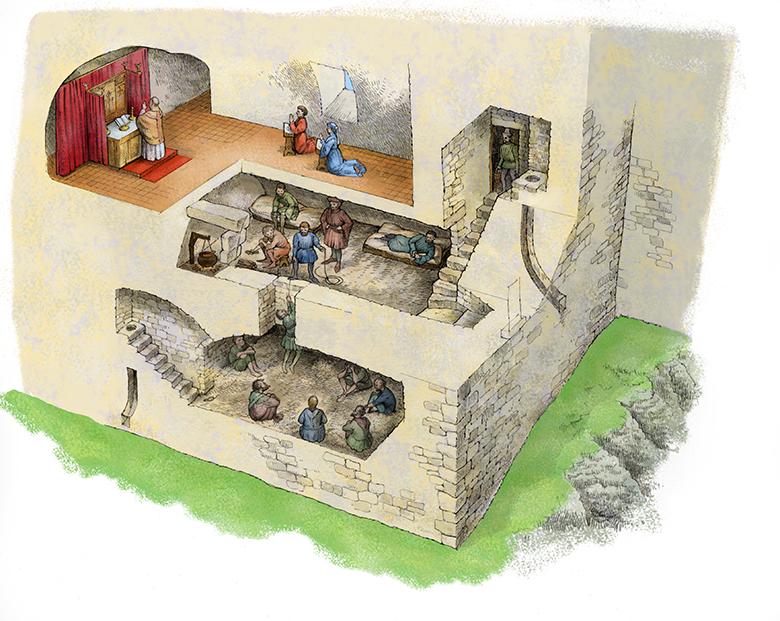

The pit-prison at Dirleton Castle, where the ‘witches’ would likely have been held.

Agnes confessed that eighteen weeks previously she had been visited at her home in Dirleton by a woman from Longniddry who had recently been burnt to death as a witch. She testified that the woman:

did use fearefull curses and execrations, intysing the said Agnes to become the devill’s servant.”

Later the same day, the devil appeared to her

in the liknesse of a black dun dogge and went up and doun the hous, and seised upon the said Agnes her cloths, and therafter, turning into the liknesse of a black man, had carnall copulation with her.”

It is unclear whether black referred to his clothing, hair, or skin, but the colour was associated with evil. Through this act she renounced Christ and became, it was believed, a witch.

A few days later, at twilight, Agnes attended “a meeting of the devil and sundrie others with him upon the green of Diriltoun”. She told the court that they all danced together. There she recognised fellow witches Patrik Watsone of nearby West Fenton, his wife Manie Halieburton, and Bessie Hogge. Agnes’s statement was sufficient evidence for the presbytery to instigate a trial.

This reconstruction drawing shows how the chapel, pit and prison at Dirleton Castle were connected.

Manie Halieburton and Patrik Watsone

Manie was likewise held prisoner in Dirleton Castle before being questioned. She had been accused by Agnes and by her own husband, Patrik.

She confessed that eighteen years before, when their daughter was sick, the devil had appeared in the likeness of a man. He tricked the couple, “calling himself a phisition (physician)”. She and Patrik provided him with bread and ale and paid him two English shillings for his service.

One morning, when Patrik was out, the devil ‘had carnall copulatioun’ with Manie. Like Agnes, Manie was forced to become the devil’s servant. Manie lamented that:

hir dochter had the wyte (blame) of all hir woe, wissing scho had nevir bene borne”

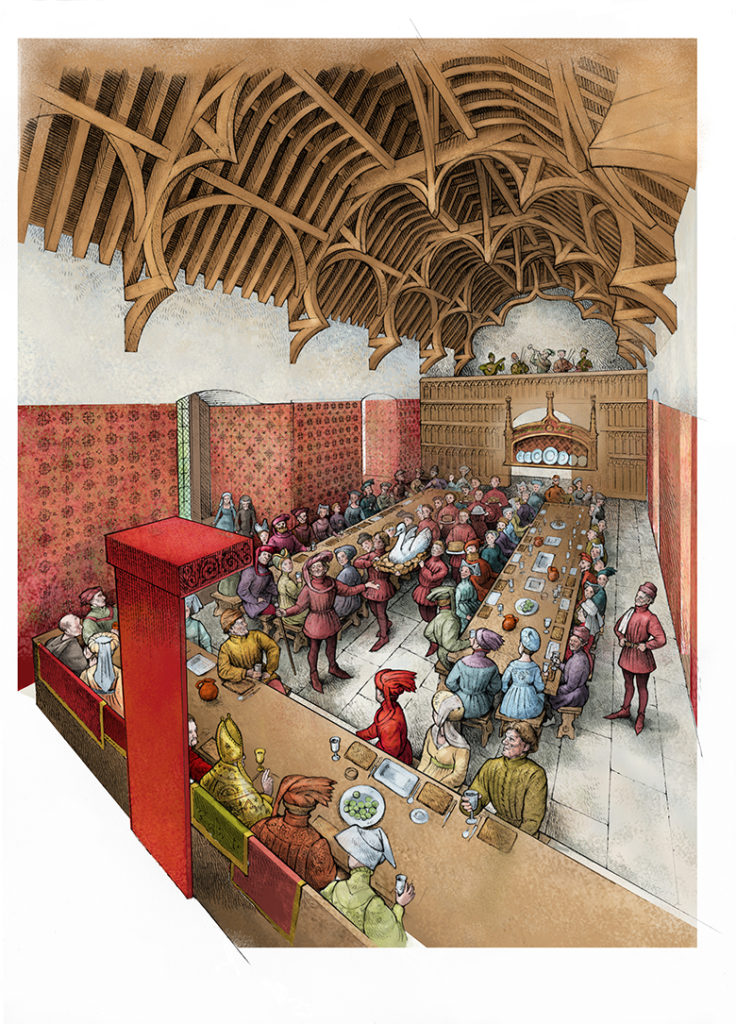

Both Manie and Patrik were taken before renowned ‘witch pricker’ John Kincaid in the great hall of Dirleton Castle. There, he searched their bodies for the devil’s mark. This was a place on the body, insensitive to pain, which the devil allegedly marked when he made made his pacts with witches.

The Great Hall at Dirleton Castle where John Kincaid searched Manie and Patrik for the devil’s mark.

Kincaid testified:

I fand the divellis marke upon the baksyde of the said Patrik Watson a little under the point of his left shoulder, and upon the left syde of the said Meinie Halliburton hir neck a little abone hir left shoulder, whairof they wer not sensible, nether came furth thairof any bloode.”

The evidence against Manie and Patrik was sufficient to bring them to trial, too.

This reconstruction drawing shows how the Great Hall at Dirleton Castle may have looked. Here it’s being used for a banquet, rather than as the stage of the witch trials.

Bessie Hogge, Marione Meik and Margaret Goodfellow

Three further Dirleton women were accused of witchcraft in 1649: Bessie Hogge, who had been seen dancing with the devil, Marione Meik, and Margaret Goodfellow. The written evidence of their interrogations and confessions hasn’t survived, but the presbytery again had enough evidence against them to instigate their trials.

The reasons for accused witches’ confessions are unknown. They may have been intimidated by their interrogators, hallucinating from sleep deprivation, or knew that their fate was sealed and it was pointless to resist. They were pressured to name other witches. Husbands who defended their wives may have come under suspicion themselves – perhaps this is what led Patrik to accuse Manie.

What happened next?

Once a presbytery had obtained witness statements and witches’ confessions, it appealed to the central authorities – in this case, parliament – for a commission to try the suspected witches. Most were then tried by the local landowner. Although evidence of the outcome of these trials hasn’t survived, they were very often a formality, and the witches’ confessions almost guaranteed their execution, usually by strangulation. This is what we think happened to Agnes, Manie, Patrik, Bessie, Marione, and Margaret.

Take a look at…

Learn more about the people accused of witchcraft in Scotland by searching the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft database. You can also view an interactive map with their places of residence.

A campaign called Witches of Scotland has recently been launched to get posthumous justice for those convicted of witchcraft, as well as to create a national memorial.