12 February 1429 is the anniversary of the Battle of the Herrings. French and Scottish forces launched an unsuccessful ambush on an English convoy taking supplies to their army, which was blockading the city of Orléans. Why is this failed attack so important in the story of Joan of Arc? Read on to find out.

A city under seige

Between October 1428 and May 1429, the prosperous city of Orléans was under siege by the English. The city, which lies 70 miles south-west of Paris, held strategic and symbolic significance for both sides in the Hundred Years War – a long-running conflict for control of the French crown.

An anonymous citizen recorded that they ‘fired stones that weighed 824 pounds and did much ill and damage to the city and many houses and fine buildings thereof’.

Once, a stone crashed through the roof of a house and on to the table of a man who was dining at it. On 30 January 1429 the townspeople were enraged to see that English soldiers had removed the poles supporting the vines of nearby vineyards to use as firewood. The people of Orléans retaliated by making an outward attack and taking fourteen prisoners.

The defenders of Orléans already included a number Scottish soldiers.

During the late medieval period, many Scots travelled to France as professional soldiers. It was possible to make a good living in this way, as well as to aid Scotland’s ally against England.

We know the French military commander, Étienne de Vignolles (known as La Hire) had Scots serving under him. Another Scot, John Carmichael, was the bishop of Orléans during the siege, having been appointed in 1426.

The Battle of the Herrings

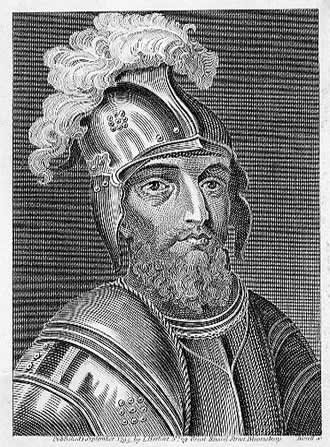

In February 1429, just over two months ahead of Joan’s arrival, Scottish reinforcements made their way to Orléans. These troops were led by Sir John Stewart of Darnley. Stewart was an experienced Scottish knight who had been the constable of the Scottish army in France from 1420. His service was rewarded with various titles and lands in France. In 1423 he had lost an eye in the battle of Cravant and would ultimately lose his life in Orléans.

Sir John Stewart of Darnley.

Andrew Birrell (fl.1794-1805), an engraver, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The timing of the Scottish arrival at Orléans was fortunate. The defenders had heard that a convoy of weapons and food supplies was making its way from English-held Paris to the besieging army. It had three hundred wagons carrying crossbows, cannons, cannonballs, and barrels of herring. The period of Lent was approaching in which medieval Christians substituted meat for fish. These precious supplies were escorted by 1,500 troops.

On 12 February 1429, Stewart and the count of Clermont left Orléans with their troops to intercept this supply train at Rouvray. The English stopped the convoy, turned it into ‘a park of wagons in the fashion of barriers’, and planted sharpened spikes all around. The count of Clermont forbade any attack before his own reinforcements arrived, but Stewart did not wait and led a charge of around 400 men towards the wagons. The English soldiers ‘rushed forth hastily from their park and struck the French, who were mostly on foot, and put them to flight in disarray.’

The aftermath

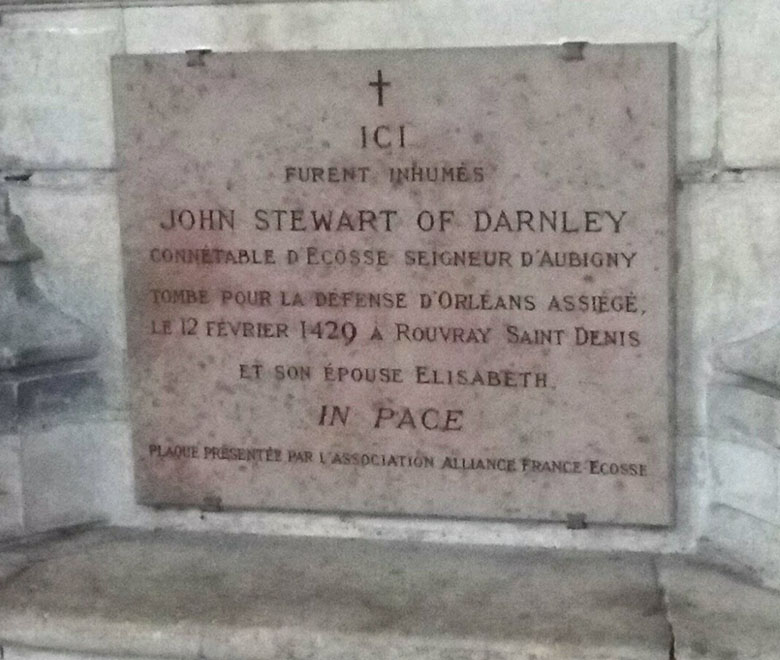

The French fled and Clermont survived, but others weren’t so lucky. Among the dead were Stewart and his brother William. Their bodies, and those of the French commanders who had died, were taken into Orléans and buried in the cathedral.

Tomb of John Stewart of Darnley in Saint-Croix Cathedral, Orléans.

Alanobrien, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Eight years earlier Stewart had paid for daily masses to be sung in the church that would become his resting place. His wife Elizabeth is buried beside him. She had followed him to France and died just 10 months after her husband.

The defeat caused many leaders on the French side – including the Scottish bishop John Carmichael – to flee the town.

Joan of Arc has a vision of defeat

You may be asking why this unsuccessful attack is of note. Well, it provided a pivotal moment in the story of the French hero, Joan of Arc.

The young peasant woman became a leading figure in the Hundred Years War after she came to the attention of the Charles VII. Known as the Dauphin, Charles was crowned king in the summer of 1429, in part thanks to Joan. The teenager had claimed that she received visions of angels and saints. They instructed her to support Charles VII and recover France from English domination.

The story goes that as the Battle of the Herrings was taking place, Joan was nearly 200 miles away in a town called Vaucoleurs. She was ardently trying to convince the military captain Robert de Baudricort that she was channelling messages from God.

He was apparently sceptical. But legend has it that Joan told him of a terrible defeat near Orléans. She proclaimed: “The Dauphin’s arms had that day suffered a great reverse near Orléans”. Days later, when a messenger arrived with news from the Battle of the Herrings, Baudricort was convinced to take Joan seriously. He arranged for her to meet with the king.

Joan was escorted to the Royal Court in Chinon, a journey of over 270 miles. At the court, she petitioned the king for permission to travel with the army and wear protective armour. The king deliberated for a while, but in the end accepted her request. By the end of April 1429 Joan joined the French and Scottish troops at Orléans.

Whether you believe these divine prophesies were genuine, they were useful to the king and made Joan an iconic figure in the ongoing Hundred Years War. And ultimately a martyr for the cause.

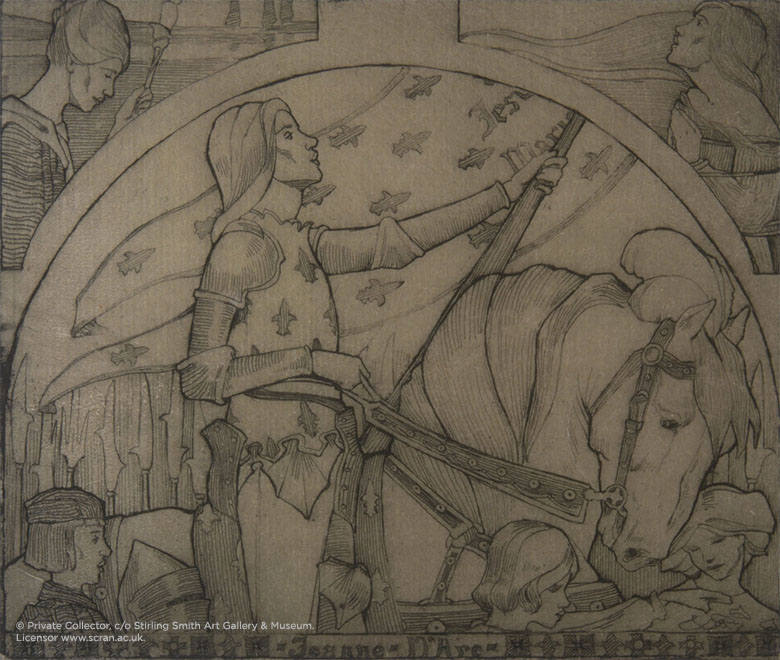

An army led by a prophet

Joan of Arc arrived at Orléans as part of a relief force. She was accompanied by 100 men-at-arms and 400 Scottish archers. Legend has it that she marched into the city to the sound of Scottish bagpipes playing “Hey Tuttie Tatie” (you might recognise it as the tune to “Scots Wha Hae”). We strongly suspect this detail of the story is a romantic embellishment of events, but if it adds colour to the way you picture the scene, then carry on!

Joan of Arc by Ann Alexander © Private Collector, c/o Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum. www.scran.ac.uk.

One by one the French captured the forts that the English had set up around the town. By 8 May the English gave up. They raised the siege and ‘set out to save themselves so swiftly that they left behind their bombards, cannons, and artillery and the greater part of their food supplies and baggage.’

The following day, Bishop Carmichael walked alongside Joan in a thanksgiving procession through Orléans. Joan’s victory ushered in a period of military success for the French, and Charles VII was crowned king of France two months later. As late as 1443 wounded Scottish veterans were still receiving charity from the city of Orléans, which remembered their contribution to the French victory. John Stewart was remembered, too, in a fifteenth century play as ‘the most valliant on earth, […] so brave and hardy’.

Banner image credit: © Estate of John Duncan. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.