Guest author Sara Sheridan takes a look at the capital’s Jewish heritage and refugees of the past who sought shelter in Scotland.

Just over a year ago, I added the word ‘Jew’ to my online profile as a stand against the rise in anti-Semitism in the UK. It was a difficult decision. I’m an atheist, but being Jewish is more than a particular belief and the rise of anti-Semitism is terrifying for people who, like me, come from a refugee background.

Russian Refugees

It’s been well over a century since the first members of the Jewish side of my family arrived in Scotland.

They left their mandated Jewish village or stetl, called Slutsk, just outside Moscow, because of anti-Jewish violence known as the pogroms. Growing up my grandmother, born in Scotland, was so terrified by the stories her nine older brothers told her about the violence they escaped she made her grandchildren promise never to return to Russia.

Like Sara’s ancestors, the Jewish Kaplan family left their home country of Russia and settled in Glasgow in the late 1800s. Image © Scottish Jewish Archive, licensed via Scran

As far as we’re aware none of the family who remained in Russia survived. Those that didn’t die in the pogroms and associated terrors, which included famine and spells in Siberia, died during World War Two. Put plainly, we’re here because my great grandparents left everything they knew.

But what empowered my family to make the decision to leave their lives behind? Not everybody in their situation did.

We still don’t know why they chose to come to Scotland, though there was a small Jewish community in Edinburgh already. The first synagogue in the city was founded on North Richmond Street in the early 1800s.

Many Jewish Lithuanians, like this shopkeeper on Edinburgh’s Church Street, also fled from Russia at the end of the 19th century to escape from ethnic and religious persecution. Image © National Museums Scotland, licensed via Scran

Edinburgh’s Early Jewish Communities

I’ve always wanted to learn more about their lives, but this isn’t easy. Jewish families of the era put a great deal of effort into assimilating into the culture of their new home.

While my great-grandmother and her generation spoke fluent Russian, Yiddish and Hebrew, they did not do so in front of the younger generation. They hoped we’d become as Scottish as anybody else if they just stuck to English. As a result, about as much Yiddish dusted my grandmother’s English, as Scots. ‘Oy vey, it’s dreich out there,’ was a typical sentence.

After a spell in London and Glasgow, my grandmother’s family settled in a new stetl in Morningside, Edinburgh. In the early 20th century, many Jewish families lived on the south side of the city.

Morningside Road in 1900 was home to a large portion of Edinburgh’s Jewish community. For a closer look at this image, visit the HES Archives on Canmore.

The synagogue, presided over by Rabbi Daiches, was on Keir Street (my grandmother was married there). My great grandmother, Catherine Vinestock, ran a fruit and vegetable shop and my great grandfather, Abraham Vinestock, set up as a master cabinet maker.

Their story is fairly typical – most Jewish families congregated on the south side of the city, including one Muriel Camberg. She was born at 160 Bruntsfield Place and later became famous as writer Muriel Spark.

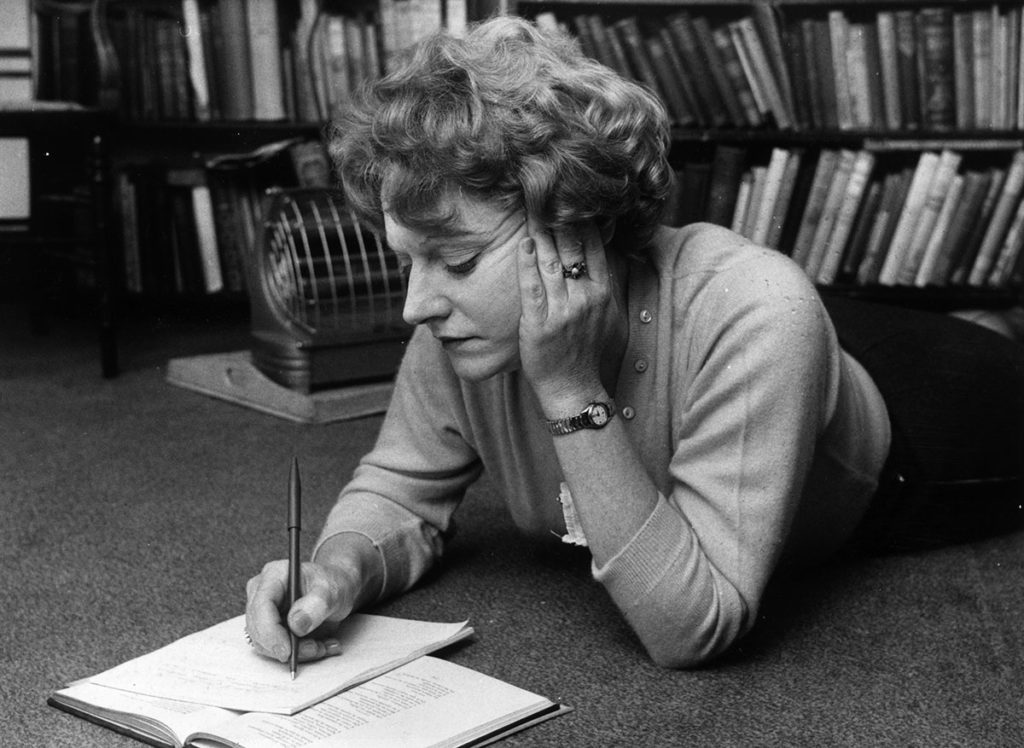

One of Scotland’s most celebrated writers, Muriel Spark was a novelist, poet and essayist with a long and successful writing career that included 22 novels. Image © Hulton Getty, licensed via Scran

So what became of my great grandfather, Abraham? All nine of his sons apprenticed with him. He was, by all accounts, a difficult master. Over the early decades of the 20th century, all nine left his workshop to set up on their own.

Four founded the Craighouse Cabinet Works on Craighouse Gardens, where they made ‘off the shelf’ furniture sold in their own outlets across Scotland. This business was hugely successful well into the 1960s, when my mother worked in the office as a secretary.

Until 1966, Keir Street was known as Graham Street and it was home to a synagogue from 1898. The building had been converted from a church at a cost of £4,000 – around £300,000 in today’s money.

Southside Synagogues, Butchers and Bakers

While many family members have researched the Jewish side of our family tree, we’ve found it all but impossible to track the Vinestocks before they came to the UK.

I could find no mention of my family in writer and historian David Daiches’s memoir. He wrote of his childhood as the son of the Edinburgh Jewish community’s Rabbi. His book, however, confirmed a community that felt familiar – very like the one I was brought up in during the 1970s. It had its own religious space, a Jewish Sunday school and several shops.

The synagogue had moved by then to its present location in a purpose-built unit on Salisbury Road. A beautiful Georgian house opposite the synagogue was our community centre (now flats).

The synagogue on Salisbury Road in Edinburgh, was built and consecrated 1932 and is still in use. Image © The Scotsman Publications Ltd, licensed via Scran

Weekly, with my mother, I visited Joseph Lurie’s Kosher Butcher (now the Press Coffee shop at 30 Buccleuch Street). It was the last of four Jewish butchers which traded in the city. We would also visit Kleinberg’s Jewish Baker at 84 East Crosscauseway, likewise the last of many similar Jewish businesses – and the first to introduce bagels to Edinburgh.

Answers In The Archive

Later, the memory of these buildings fired me to expand my routes to family research. In a bid to make connections with my forebears’ day-to-day lives, I spent several days tracking down their homes and businesses in the Historic Environment Scotland (HES) Archives at John Sinclair House in Newington.

Making a connection with the built environment I still live in seemed a good way to reach into the past. Though some of the buildings are no longer there, I found entries for many businesses in old directories in the HES Library and tracked down photographs of the addresses in the archive where I could.

These were the streets my relations lived and worked on. There was a photograph of the old synagogue on Keir Street, views of the Southside streets and images of several of the tenements in Leith where my great uncles lived after leaving Abraham Vinestock’s overbearing apprenticeship. Leith was what they could afford on their own.

Sara’s historic relatives would have shared this view of Leopold Place and Gayfield Square at the start of the 20th century. Take a closer look at this image from the HES Archives (J H B Fletcher Collection) on Canmore.

Craighouse Cabinet Works’ outlet on Greenside proved to be within a block of my other grandfather’s tailoring business on Leopold Place. This put the two Jewish sides of my family in each other’s immediate spheres. I can only wonder if this is how the match was made between my grandfather and grandmother? It seems likely.

The Vinestocks were certainly natty dressers and the grainy black and white photographs we have of them look like handmade suits were in vogue. Archive photographs of this area, dating back to before the development of the St James’ Centre, have proved particularly valuable in understanding the streets they walked – many of which are no longer there.

Renovation of the synagogue in Edinburgh’s Salisbury Road was almost complete by March 1981. Built in 1932, the building was modified to include classrooms and leisure space. Image © The Scotsman Publications Ltd, licensed via Scran

Identity In Place

I’ve learned a lot about the importance of our built environment whilst researching my family; knowledge compounded when I began remapping Scotland according to women’s history for my book Where are the Women?

I was fascinated to see how the social, political and built environment women lived in afforded them different opportunities. For Jewish women, these were certainly different to the opportunities they would have had without the emigration of family pioneers.

For example, photographer Franki Raffles shot Edinburgh’s famous Zero Tolerance campaign to raise awareness of men’s violence against women and children. She died young, giving birth to twins. Annie Altshul, who fled fascism on the Kindertransport and later transformed post-war mental health nursing practice. Or campaigner Ruth Adler who set up Amnesty International’s first Scottish office.

We are where we come from. I feel closer to my family now that I can visualise the world they lived in. It pleases me that, despite Abraham’s difficult nature, they stuck close by each other, living and working together in what was no doubt an occasionally hostile world.

More space was required for Edinburgh’s Jewish graveyards, so after the First World War, a section of Piershill Cemetery was dedicated to the community. It was the third Jewish graveyard, after Sciennes and Newington.

In the last decade many gravestones in the Jewish cemetery at Piershill were daubed with Fascist graffiti. Complacency isn’t an option. We must take every opportunity we can to celebrate these lives – not just our Jewish heritage but the incredible diversity of our culture.

It’s something we’re not always aware of in Scotland. We come from a melting pot and that’s part of what makes us who we are.

Sara Sheridan is named as one of the Saltire Society’s most influential women, past and present. She’s known for the Mirabelle Bevan mysteries, a series of historical novels based on Georgian and Victorian explorers, and has written non-fiction on the early life of Queen Victoria. With a fascination for uncovering forgotten women in history, she is an active campaigner and feminist.