Have you dared add The Terror to your TV viewing schedule yet?

The historical horror series gives a fictionalised account of the ill-fated voyage made by HMS Erebus and HMS Terror under the command of Sir John Franklin in 1845.

After bravely binge-watching the show in a matter of days, we became mildly obsessed with Franklin’s Lost Expedition, especially its connections to Scottish people and places.

So, once we’d climbed out from behind the sofa, we delved into the Historic Environment Scotland archives to explore the story further. There’s less cinematic effects and no sign of the supernatural, but the truth is equally as compelling as the fiction…

Be warned, if you don’t know the end of the Franklin story, then spoilers lie ahead!

A Voyage of Discovery

The main goal of Franklin’s expedition was a simple one: to find the North West Passage, a short cut between Europe and Asia through the icy Arctic seas.

The British Admiralty had organised numerous expeditions for this purpose since the early 1800s. Franklin himself had been second-in-command on a similar journey made in 1818, and he had led two overland missions along the Canadian Arctic coast.

A silver anchor badge belonging to one of the men on the Franklin Expedition (Scran image)

Erebus and Terror were also no strangers to icy waters, having already sailed to the Antarctic. Re-fitted with state-of-the-art technology which included steam engines and central heating systems, they were ready to begin their next epic journey in the early summer of 1845.

Armed with three years’ worth of food, a library of over 1,000 books and the extensive knowledge gathered by all those expeditions before them, Franklin and his crew of 24 officers and 110 men set sail from Greenhithe in Kent on the morning of 19 May.

A Stop in Stromness

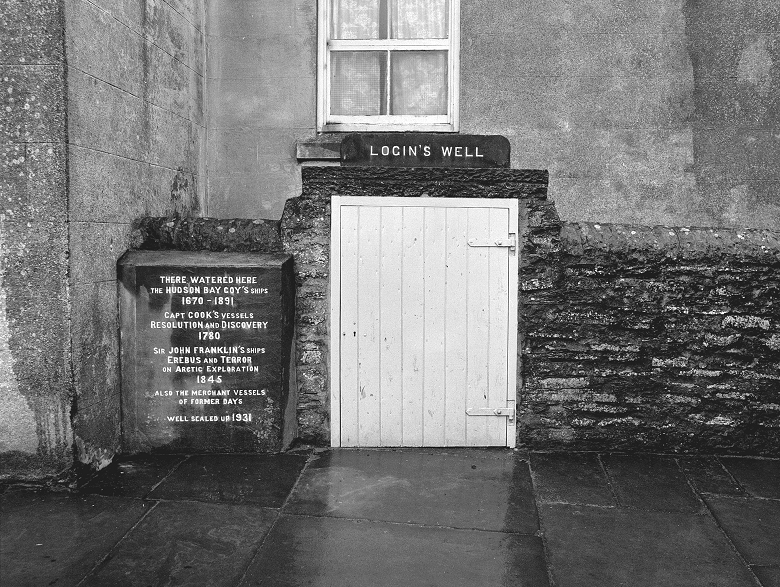

Erebus and Terror made a brief pit stop in Stromness before their 30-day passage to Greenland.

The Orkney town was long-established as a departure point for far flung exploration. From 1670 until 1891, the Hudson’s Bay Company used it as a base for servicing their Atlantic-bound ships.

It’s striking to imagine Franklin’s crew looking out over Stromness and recalling that it was to the same harbour that Captain Cook’s ships Resolution and Discovery returned in 1780. They too had been attempting to locate the Northwest Passage, but had limped home after a chaotic and unsuccessful expedition.

Stromness Harbour (Scran image)

Arctic-bound Scots

From the ships’ muster rolls we can deduce that two Orcadians left with the expedition. On Erebus, Captain of the Foretop Robert Sinclair (aged 25) and Able Seaman Thomas Work (41) both hailed from Kirkwall. They were joined by at least 15 fellow Scots:

On Erebus:

- Harry Duncan Spens Goodsir, Assistant Surgeon, Anstruther (25)

- James Reid, Ice-Master, Aberdeen (age unknown)

- Daniel Arthur, Quartermaster, Aberdeen (35)

- William Bell, Quartermaster, Dundee (36)

- John Murray, Sailmaker, Glasgow (43)

- William Clossan, Able Seaman, Shetland (25)

- Alexander Paterson, Corporal, Royal Marines, Inverness (30)

On Terror:

- John Irving, Third Lieutenant, Edinburgh (30)

- David Macdonald, Quartermaster, Peterhead (46)

- John Kenley, Quartermaster, St. Monance (44)

- Alexander Berry, Able Seaman, Fifeshire (32)

- David Leys, Able Seaman, Montrose (37)

- Magnus Manson, Able Seaman, Shetland (28)

- William Shanks, Able Seaman, Dundee (29)

- William Sinclair, Able Seaman, Scalloway, Shetland (30)

Closed up in 1931, Login’s Well on Stromness main street was once a water supply for the town and for ships using the harbour. A plaque notes how it was used by Captain Cook and John Franklin (Canmore image)

The Lieutenant and the Surgeon

Viewers of The Terror will recognise two of the above names – Lieutenant John Irving and Harry Goodsir – as key characters in the series.

The real John Irving was born on Princes Street, Edinburgh in 1815. He joined the Navy in 1828 and climbed the ranks, despite having to return to Scotland after various failed ventures. The Franklin Expedition presented a good opportunity for him to get things back on track.

In 1819, across the Forth, Harry Goodsir was born into a medical family in Anstruther. His grandfather, father and three of his brothers were doctors and the family ran a practice in Lower Largo, a few miles further down the Fife coast.

Anstruther, birthplace of Harry Goodsir, in the late 1800s (Canmore image)

True to family form, Harry studied at the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh, becoming a member of the Royal Medical Society. He assisted his elder brother, John, in pioneering work on cell theory. Before joining the Franklin expedition, Goodsir was Conservator at the Surgeon’s Hall Museum.

Though listed on the rolls as an Assistant Surgeon, Goodsir also served as a naturalist, using the trip as an opportunity to study the Arctic environment. He sent a detailed study of insects from Erebus while docked at Disko Island, west of Greenland, in June 1845.

Harry Goodsir was Conservator at Edinburgh Surgeon’s Hall Museum before going to sea aboard Erebus (Canmore image)

Frozen In

The letters sent from Disko Island would be the last time anyone in Britain heard from the Franklin expedition. Erebus and Terror were last seen by Europeans in late July, when they encountered whaling ships in Baffin Bay. From there they headed across the Lancaster Sound – and never returned.

Nobody knows exactly what happened next. A note left by the expedition in a cairn known as Victory Point on the northwestern coast of King William Island in May 1847 gives us at least some indication.

It states “all was well” even though Terror and Erebus had been trapped in ice since September 1846. But an update made to the note just under a year later tells us that things took a major turn for the worse.

John Franklin had died on 11 June 1847, one of 23 crew members to have passed away by that point. Command had moved to his deputy, Francis Crozier, and Captain James Fitzjames. They made the decision to abandon ship and begin an arduous and desperate walk to the Canadian mainland on 26 April 1848.

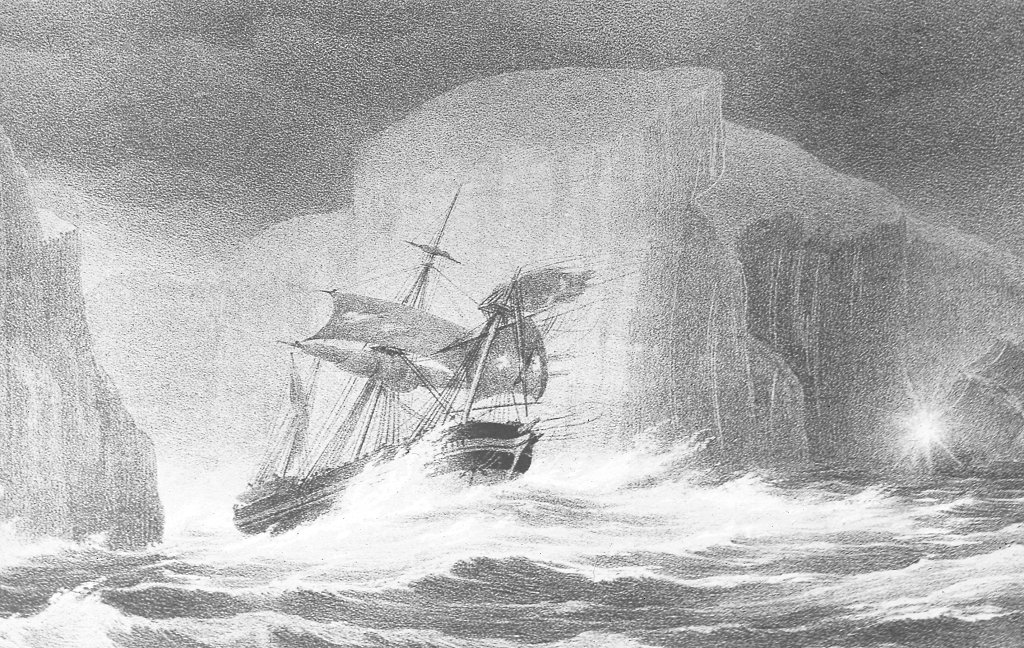

Erebus passing through a chain of icebergs. The wrecks of Erebus and Terror near King William Island in Nunavut are now designated as National Historic Site of Canada (Scran image)

Lady Franklin’s Lament

Back in Britain concern for Franklin’s party was growing. Jane Franklin, wife of Sir John, campaigned tirelessly to spur the Admiralty into action. Eventually, a reward of £20,000 (over £2 million in today’s money) was put up for anyone who could find and assist Franklin.

Meanwhile, the mystery surrounding the expedition’s fate caught the public’s imagination. A folk ballad, Lady Franklin’s Lament, became popular. It’s last verse reads:

And now my burden it gives me pain

For my long-lost Franklin I would cross the main

Ten thousand pounds I would freely give

To know on earth, that my Franklin do live

Jane Franklin certainly did “freely give” a great deal of money, funding numerous private missions to find her husband on top of the Admiralty’s efforts.

Scots to the Rescue?

One such mission was led by William Penny, an experienced whaler and Arctic explorer originally from Peterhead. A whaler and steam power pioneer, Penny is credited with mounting some of the first searches for Franklin in 1847-48 but was forced to turn back by ice.

Returning in 1850 on the aptly named Lady Franklin, he was able to find traces of the expedition’s 1845-6 winter quarters (from before they were frozen in off King William Island), including the location of three graves. Penny was joined on two of his trips by Harry Goodsir’s younger brother, Robert.

The grave of William Penny, St Nicholas Kirkyard, Aberdeen (Scran image)

Penny crossed paths with another Scot employed by Lady Franklin. Sir John Ross, a 72-year-old from Stranraer, was captain of a mission on the Felix.

The voyage proved to be an inglorious end to Ross’ career. Scurvy broke out onboard the Felix and he was forced to return in 1851, empty-handed, save for the rumours he’d heard from the local population that Franklin and all of his men had perished.

John Rae and the Unfortunate Truth

Ross believed the rumours to be true, but he couldn’t convince his peers. Lady Franklin angrily withdrew her support. But as mission after mission found no trace of Erebus and Terror, and the Admiralty’s reward remained unclaimed, even the most optimistic must have started to lose hope.

However, there was another experienced Scottish explorer waiting in the wings, ready to try and bring home news of the lost expedition.

A replica of a portrait of Dr John Rae. The original was painted by Stephen Pearce in 1853. (Scran image)

John Rae (the namesake for our own Rae Project) was born at the Hall of Clestrain in Orphir, Orkney in 1813. A graduate of the University of Edinburgh, he learned Arctic survival skills while working for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

He was renowned for his stamina, ability to travel long distances with minimal supplies, and crucially, his ability to understand and communicate with the indigenous populations.

Rae had been dispatched on an overland rescue mission in the summer of 1848, initially accompanied Dumfries-born John Richardson. He continued searching well into the 1850s.

A Terrible Fate

By July 1854, Rae had collected oral testimonies from a number of indigenous groups.

They spoke of sightings of a party of malnourished-looking white men, and of the discovery of some 30 bodies, some buried, others in tents or makeshift shelters. Chillingly, some of the corpses were said to have showed sign of cannibalism.

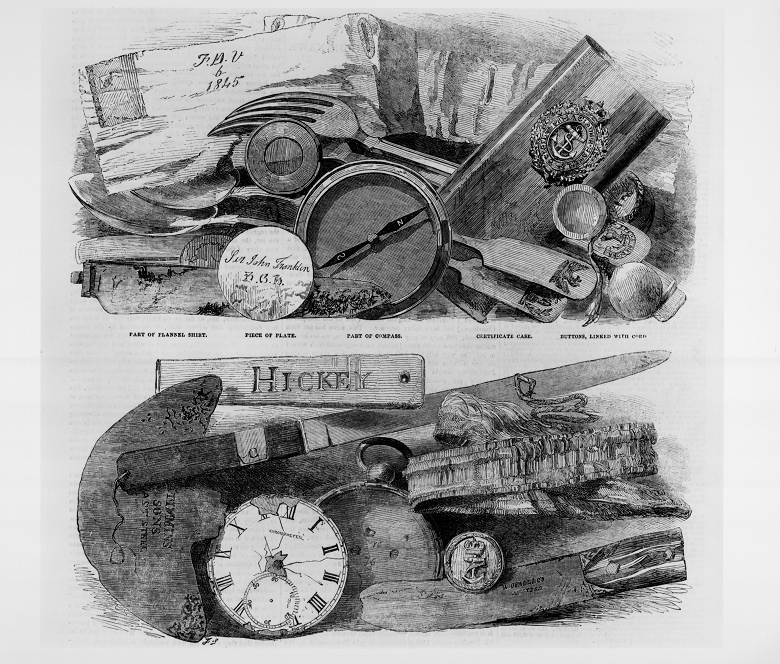

An illustration of some of the personal items given to Rae. Viewers of ‘The Terror’ will note, with a shudder, the inscription of the name Hickey… (Scran image)

The accounts were supported by physical evidence. Rae was able to acquire artefacts, including watches, cutlery and other personal items, which were identifiable as having once belonged to crew members of Erebus and Terror. One was a silver plate with “Sir John Franklin” inscribed on the back.

It was enough for Rae to conclude that the expedition had suffered “a fate terrible as the imagination can conceive.”

Forks acquired by Rae which are believed to have belonged to John Franklin and James Fitzjames (Scran image)

Fury and The Fox

Like John Ross before him, John Rae’s findings – especially the suggestion of cannibalism – were not well received. Though he did receive some of the reward money, he was not given public recognition for his work and returned home to anger.

Lady Franklin, supported by a celebrity voice in the form of Charles Dickens, publicly scorned Rae and the Inuits he had interviewed.

Nonetheless, the authorities accepted that Franklin and his men had perished, officially labelling them deceased in service. A desperate Jane Franklin personally commissioned one more expedition…

The Fox, used for Jane Franklin’s last-ditch rescue mission, was built at Alexander Hall and Sons shipyard in Aberdeen (Canmore image)

Lady Franklin purchased an Aberdeen-built steam schooner, the Fox, which set sail in July 1857. It was the Fox that discovered the Victory Point note, along with bodies and abandoned equipment, confirming Rae’s findings.

It was clear that any subsequent missions to locate Erebus and Terror would be for recovery purposes rather than rescue.

Irving (and Goodsir?) Return Home

John Rae’s grave (Scran image)

John Rae died in 1893 and is buried at St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall. 300 miles south, in Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh, another grave associated with the Franklin Expedition can be found.

The body of Lieutenant John Irving was found by a US Army expedition in the late 1870s. It was returned to Scotland and buried with full honours.

John Irving’s grave in Dean Cemetery

And what of Harry Goodsir? A few years earlier, a body from the expedition had been found and interred at the Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich. It was identified as the remains of an Erebus lieutenant called Henry Le Vesconte.

In 2009 the skeleton was re-examined, with intriguing results. A facial reconstruction showed an excellent match with Harry Goodsir. Dental data pointed to an upbringing in the east of Scotland (Le Vesconte was from southwest England). There was also evidence of a gold filling, rare for the 1840s.

Is it mere coincidence that the Goodsir family were close friends with the Edinburgh dentist Robert Nasmyth, who was renowned for such work?

A carving on John Irving’s grave depicts a scene from the Franklin Expedition

A Chance to Reflect

While a “Terror Tour” is unlikely to challenge Outlander location packages, there’s plenty of places that you can visit to reflect on the tragic story of the Franklin Expedition.

It could be one of the memorials to John Rae in Kirkwall or Stromness, the grave of John Irving or William Penny or the one-time stomping grounds of Harry Goodsir in Edinburgh and Fife.

The memorial to John Rae inside St Magnus’ Cathedral (Scran image)

One location that’s a bit more difficult to reach, however, is Out Stack, or Oosta. This tiny rocky island about 600 metres from Muckle Flugga, Shetland, is the northernmost tip of Scotland.

It was to this wild and desolate spot that Jane Franklin travelled after hearing Rae’s news. She wanted to be as close as possible to her husband, lost, far away in the frozen north.

Out Stack lies around 600 metres northeast of Muckle Flugga and its lighthouse (Canmore image)

This blog is illustrated with archive images available on Canmore, the online home of the National Record of the Historic Environment and Scran, which offers access to over 400,000 media items relating to Scotland’s culture and heritage.

The Terror is available on BBC iPlayer and is based on a novel of the same name by Dan Simmons.