The story of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH) is tied inextricably to the First World War.

By the end of 1918, over 1,000 women had served with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. They endured extremely difficult conditions to care for military and civilians alike.

But their compassion and bravery is not well known in Scotland. The skills and support offered by these doctors, nurses and more were not recognised by the War Office. Instead, it was Britain’s allies that gave them the opportunity to take care of their wounded.

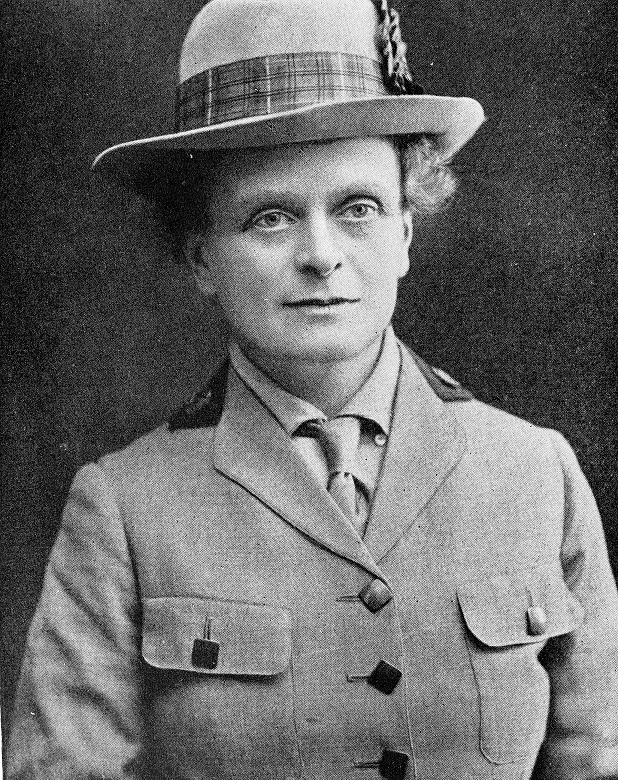

Dr Elise Inglis (Image licensed via Scran)

“Go home and sit still”

At the outbreak of the First World War, Dr Elsie Inglis immediately recognised there would be need for medical staff.

A prominent suffragist, she had studied at Sophia Jex-Blake’s Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women and later set up a rival medical school, the College of Medicine for Women. She quickly acquired volunteers to support the war effort.

Upon offering their services to the War Office, Dr Inglis received the reply:

My good lady, go home and sit still.”

Needless to say, she did not follow this advice and instead offered their services to Britain’s allies, who duly accepted.

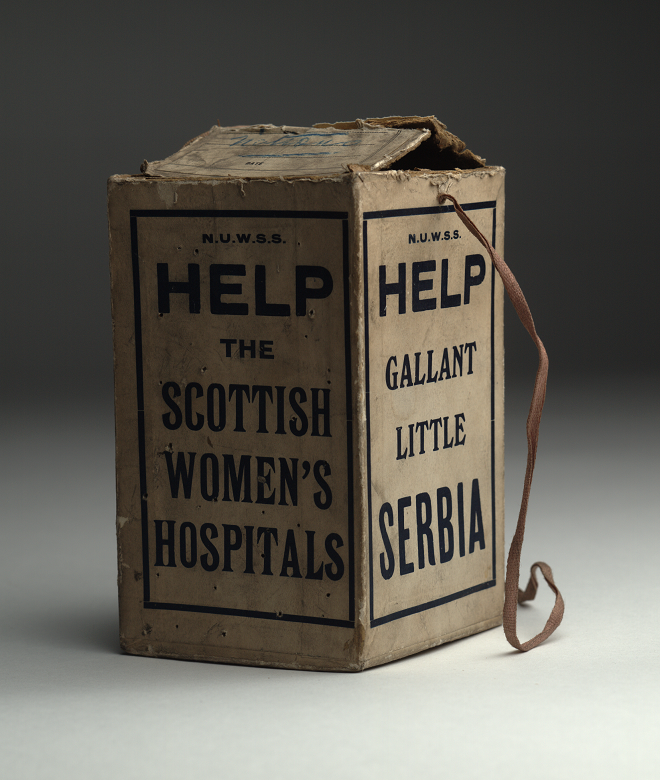

A collecting box used to raise funds for the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (Image licensed via Scran)

The first Scottish Women’s Hospitals

In 1914, fundraising began in earnest to establish the SWH. In partnership with the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), Dr Inglis attracted donations and volunteers from all over the world, stating:

The ordinary male disbelief in our capacity cannot be argued away; it can only be worked away.”

Women were recruited, not only as doctors and nurses, but also orderlies, drivers, cooks and administrators. The non-medical roles were filled by women from all walks of life, including actresses Cicely Hamilton and Vera Holme, and classical archaeologist Hilda Lorimer.

SWH Units were often named after organisations’ substantial donations, such as the “American Unit”. Before long, they had raised enough funds to equip and send units all over Europe to care for sick and wounded soldiers. They would also end up treating civilians and refugees.

A thistle-shaped flag, sold on Scottish Women’s Allies Hospital Day (licensed via Scran)

Life in the SWH

Initially met with scepticism, the SWH quickly gained admiration and respect wherever they went.

The women would work around the clock with extraordinarily little sleep, sometimes for days at a time, just to cope with the influx of wounded during heavy fighting. They would speedily refurbish basic accommodation into workable hospitals and found themselves caught up in epidemics and the chaos of retreat on more than one occasion.

Nevertheless, they were determined to make hospital life as pleasant as possible by organising friendly competitions, concerts and Christmas celebrations.

The women will have been aware that their performance would not only be used to judge the competence of female doctors, but it could also influence the outcome of the women’s suffrage movement.

The Nursing Sisters at the Scottish Womens Hospital in Salonika in May 1917 (licensed via Scran)

Treatment on the frontline

Perhaps the best known, but not the first, SWH hospital was at the Abbey of Royaumont, not far from Paris.

Led by renowned surgeon Frances Ivens, the Unit arrived at the Abbey in December 1914. They were met with a building that had suffered from years of neglect, with no heating or electricity. The women worked hard to ready the Abbey and they began to take patients on 11 January 1915.

Despite fuel shortages, drainage problems and the skepticism of the French authorities, the SWH was ultimately held in high regard.

Pioneering treatments were carried out in the hospital, including treatment for “gas gangrene”. Considering the severity of the wounds and intense pressure on the staff, the hospital had a remarkably low mortality rate.

When it finally closed in March 1919, most of the medical equipment was donated to the hospital in Lille and other fittings to the village of Villeneuves, both of which had been devastated during the war.

A flag sold to raise funds for SWH (licensed via Scran)

The SWH in Serbia

In mid-December 1914, the 1st Serbian Unit, led by Dr Eleanor Soltau, left for Serbia. It would soon be followed by another two Units. Upon arrival, Dr Soltau wrote:

I shall never forget the scene of misery, suffering and desolation we found there.”

They were sent to Kragujevac where control of a hospital was handed to them. Despite the minimal fighting in the region, the Unit still had to contend with crude facilities, chronic overcrowding and a shortage of medical supplies. Just like Ivens’ Unit in Royaumont, the Serbian Unit worked tirelessly to bring the hospital up to a standard for their patients.

A typhus epidemic followed soon after their arrival. In February, they established a new ward for the typhus patients, overseen by Sister Louisa Jordan, who had experience from Shotts Fever Hospital. Sadly, Jordan succumbed to the disease soon after.

Dr Soltau later fell ill with diptheria and Dr Elsie Inglis arrived to take her place.

A scene from a Scottish Women’s Hospital in Serbia (image licensed via Scran)

The Great Retreat

In the winter of 1915, Serbia was again invaded.

Some members of the Serbian Unit, including Dr Inglis, decided to remain with the patients and were subsequently captured by the invading armies. Others left, accompanying the Serbs over the mountains to the Adriatic coast.

Described as “the passing of a whole nation into exile”, this desperate withdrawal became known as the ‘Great Retreat’ and would kill tens of thousands. The perilous seven-week journey was marred by hostile weather conditions, lack of food and little sleep. One SWH nurse, Caroline Toughill, was killed when her van ran off the road.

Eventually, the remaining members of the Serbian Unit were evacuated. They soon founded a new hospital on the island of Corsica for the displaced population.

Facilities included a maternity unit, outpatient department, infectious diseases wards and four outlying dispensaries. Astonished by their devotion, the Serbian Prime Minister, M. Pachitch, would later write to the SWH Executive Committee:

The Serbian nation will never forget what the Scottish women have done for them.”

Return to Serbia

After her release and repatriation, Dr Inglis remained undeterred. She organised another SWH Unit for the Serbian division of the Russian army and was rejoined by other veterans of the 1st Serbian Unit.

A medal for the Serbian Order of St Sava, 5th class, awarded to Miss A. Lindsay in recognition of her work with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Serbia (licensed via Scran)

Once again, they were caught up in several retreats and their support was desperately needed. The division faced an almost overwhelming number of casualties in Galatz and Bralia, and the women of the SWH operated on as little as three hours sleep a night.

In November 1917, the Russian Revolution saw a full uprising against the government. Russia withdrew from the War. By then, the Serbian Unit was facing their own crisis – supplies were running low and Inglis’ health was deteriorating.

She was accompanied back to Britain by a detachment of Serbian soldiers. Sadly, Dr Inglis died of cancer on 26 November 1917, shortly after arriving in Britain. Her last request of the SWH was to “make sure the Serbs have their hospitals and transport, for they do need them.”

After her death, a Unit named for her was equipped and ready by February 1918. The Elsie Englis Unit journeyed through Russia, this time with the patronage of the British War Office, and worked in Sarajevo until the unit was disbanded in April 1919.

Remembering the SWH

Nurses and doctors on a Pageant Day at the Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital, opened with the remaining Scottish Women’s Hopsitals funds (licensed via Scran)

While disregarded by the British War Office for much of the war, many SWH staff were highly decorated by Britain’s allies.

Among them, twenty-three of the staff of Royaumont would receive a Croix de Guerre, a French military decoration for gallant action in war. Inglis herself received five medals in total, including the Serbian Order of the White Eagle (1st Class) in 1916.

In a letter to her sister in 1918, E Courtauld asked:

[Where] in the annals of history before these last four revolutionary years is to be found any instance of a women’s unit receiving military decorations at the hands of a foreign government for direct participation in war?”

The nurses and doctor who died in the 1915 typhoid epidemic are honoured annually in Serbia; their names better remembered there.

A performer tells the story of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals at a living history event at Edinburgh Castle

Closer to home, the SWH are honoured alongside other women who served during World War I in a commemorative window in York Minster, and with a stone at the Scottish National War Memorial.

In 1925, the remaining funds from the Scottish Women’s Hospitals were used to establish the Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital in Abbeyhill, Edinburgh. It closed in 1988, despite public protests.

The courage and perseverance of those who served with the SWH is something that should not be forgotten.

There’s much more on the significant achievements of Scotland’s well-known women, alongside the unsung heroines who quietly shaped the country we know today, at our Women of Scotland online exhibition.