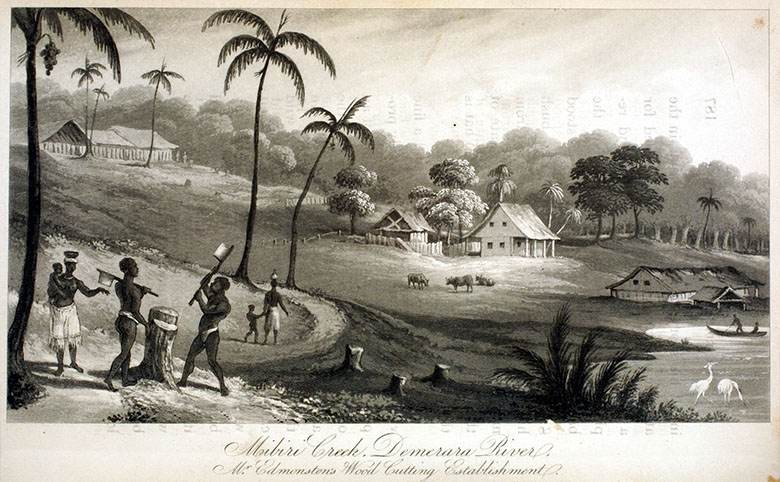

John Edmonstone was a man originally enslaved on a timber plantation located in Mibiri Creek. This is a remote and swampy area in Demerara, that later became part of the country of Guyana. How did he end up owning a successful business in Edinburgh in the early nineteenth century?

Stolen lives: the horrors of life for enslaved people in Demerara

The plantation at Mibiri was one owned by Scotsman Charles Edmonstone. Charles’ wife Helen had both indigenous South American and Scottish heritage.

“Timber Estate, British Guiana (Demerara), 1834”. This engraving shows the Mibiri Creek estate. (Image: Public domain, via Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora.)

Charles Edmonstone was one of the most prominent plantation owners in Demerara. He was well known for ‘ensuring the security’ of the colony. This meant he led expeditions to re-enslave people who had emancipated themselves from plantations to join free Maroon communities. Maroon communities were settlements of people of African heritage who managed to build a life away from slavery in remote areas. These communities quite often came together with Indigenous communities, building interracial families and communities. Charles Edmonstone would organise search parties to re-capture people who had escaped slavery to settle in Maroon communities. Those who refused to return to an enslaved life were executed on Charles’ orders.

Helen’s lineage and connections gave Charles and his helpers access to unique knowledge of the terrain in Guyana. With assistance from Indigenous people, Charles was regularly triumphant in these deadly missions.

Charles was presented with swords and various decorative tokens by the Governor before he left for Scotland to reward him for decades of upholding the system of slavery at any cost, and noted for his ‘integrity and humanity’.

From South America to Scotland

When Charles Edmonstone returned to Scotland with his family, he brought members of his household with him from Guyana. Among the household who relocated to Cardross Park near Glasgow was John Edmonstone.

This 19th century villa stands on the site of the house that Charles and Helen Edmonstone would have relocated to in Scotland. It was part of the Kilmahew Estate. Find out more on Canmore.

We don’t know much of John’s life before he came to Scotland. However, we do know that he had learned the art of taxidermy from Scottish naturalist Charles Waterton, a close friend of the Edmonstone family.

Upon arriving in Scotland, John was able to live as a free man. This was nearly twenty years before the legal end of chattel slavery in the British Caribbean in 1838. From this point, John had the opportunity to build a successful and independent life in Scotland, very different from the one he left behind.

Emancipation: a prolonged end to slavery in the Caribbean

On reaching Scotland, relationships within the family started to fall apart. Helen, bitter at the favouritism shown by Charles to a woman who was enslaved in her name, refused to free her. This lead to a breakdown in their marriage and Helen’s subsequent addiction to opium.

Charles’ will, written in 1827 and proved in 1835, mentioned a mixed-race girl called Jeanie living with him, to whom he left £1000. It also stipulated freedom for three women: Catharine, Betty and Cecilia. We know these women did not come to Scotland. It is likely that in 1835 they would have been working as unpaid labourers under the “apprenticeship” system that replaced the chattel slavery system until 1838. The reality was that this was slavery by another name, which was often met with strikes and sabotage by the angry workers. Apprentices continued to work unpaid and were often still subject to cruel punishments.

John’s situation was different from the women. He was able to use his skills to support himself in Scotland and left behind this unhappy household in Cardross Park.

Building a new life

The skills John Edmonstone learned from Waterton were very specific. For example, he knew how to remove the skin of a snake to preserve and harden its skin with mercury chloride. There are records of him selling exotic animal specimens to the museum in Glasgow.

Records show John Edmonstone lived at 37 Lothian Street.

John moved across to Edinburgh some time shortly after his arrival. By 1823, he had his own successful shop on Lothian Street. From his shop he sold preserved specimens to the museum, including birds and the skin of a 15 foot long boa constrictor.

He also taught taxidermy to the students at the University of Edinburgh at the rate of a guinea per hour. In a way, he became Scotland’s first Black university lecturer.

A young Darwin

Living just a few door’s down from Edmonstone’s shop, at Mrs McKay’s boarding house, was the student Charles Darwin.

A portrait of the young Charles Darwin be George Richmond. (Image: public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.)

Young Charles was sick to the back teeth of studying medicine. He was disgusted by cutting up dead bodies, and had been complaining bitterly to his father in letters home about the professors because he considered them boring and useless.

Darwin was intrigued to hear of a young man who had been a former servant of Dr Duncan, who had been one of the professors at the university. He was excited to hear that Edmonstone was now offering popular and unusual lessons in taxidermy to students.

The exhibition hall in the Medical School at Edinburgh University, Teviot Place in 1895. Perhaps a young Charles Darwin would have been familiar with some of these exhibits. Explore this image in more detail on Canmore.

However, his desperate pleas to leave Edinburgh and come home were resisted by his father, who expected he and his brother Erasmus to follow in the family footsteps. It wasn’t that Charles didn’t enjoy learning. He was just far more interested in anything to do with the natural world. He and his older brother took every opportunity they could to read in the extensive library. Charles was also making good use of the dazzling array of learned societies in the city, and he jumped at the chance of taking lessons from Edmonstone.

Taxidermy: an important part in understanding evolution

In 1826, for two months around his seventeenth birthday, Darwin enjoyed taking lessons with Edmonstone for an hour each day. It seems like they developed a good relationship. In a letter to his sister, he declared his valued teacher to be a “very pleasant and intelligent man”. As well as the skills of taxidermy, he gained a thorough knowledge of the fauna and flora of South America. No doubt this would have held him in good stead for his later career as a famous naturalist.

Darwin was finally granted his wish to give up medicine, and he left Edinburgh. Shortly after, he was given the exciting opportunity to sail around the world on the famous SS Beagle as a personal companion Captain FitzRoy. One of his first collecting expeditions was into the forests of South America.

When he reached Argentina, he was able to preserve eighty different types of birds during one two week expedition. With the help of John Gould on his return, he was able to identify the way the beaks of finches from the Galapagos Islands had adapted over time depending on the food available in their area. This formed the basis of his revolutionary theory of natural selection and his famous 1857 book the Origin of Species.

A hopefully happy life

It seems hopeful that John Edmonstone’s life also continued in a positive direction after his arrival in Scotland. As a free man, he was able to pursue a life desired by many. He built a thriving business, earned the respect of his community and a lived happy family life.

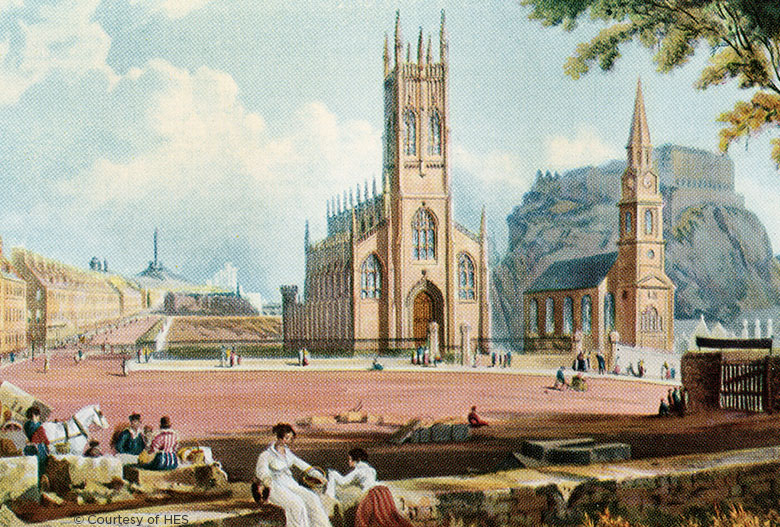

Mary Kerr was a young lady who also lived at 33 Lothian Street, in a house directly located between Darwin and Edmonstone. It looks as if John and his ‘girl next door’ were sweethearts, and likely to have married. The banns were read on three consecutive Sundays in 1824 at St Cuthbert’s Church. Reading the banns was the custom in Scotland at the time. Thankfully, there were no objections raised to the marriage from the congregation at any point.

A postcard from 1824 showing St Cuthbert’s Church (right). Take a closer look on Canmore.

As the fashion for stuffed birds and animals became popular in the Victorian era, Edmonstone would have enjoyed increasing amounts of custom. Queen Victoria, in particular, was a keen collector of taxidermy.

On the up and up

Thanks to the popularity of stuffed animals, Edmonstone moved to new and more expensive premises on South St David St. He operated out of these more central and prestigious premises between 1826 and 1843. Furthermore, the 1841 census shows a 45 year old shopkeeper by the name of John Edmonstone living with a woman named Mary and their three children. It was noted that he was born outside of Scotland. Their residence was at James Court, a quiet courtyard just off the Royal Mile.

This 19th century view of the Lawnmarket is the type of bustling street scene that would have been familiar to John Edmonstone. The entrance to James Court is through a close on the left of this image. Zoom in on this picture in Canmore.

Marking Edmonstone’s life

In 2009, a commemorative plaque was put up in Lothian Street to remember John Edmonstone and his achievements. Approved by Edinburgh Council, the plaque was made by the Wedgwood family. The Wedgwoods were admired for their anti-slavery activism. For instance, in the eighteenth century, they made of abolitionist plaques and brooches. The founder of Wedgwood and Sons Pottery was Josiah Wedgwood, who was none other than Charles Darwin’s own grandfather.

This plaque to Charles Darwin is less than 100m from the spot where John Edmonstone’s plaque used to hang.

It’s a little concerning then, that the first plaque put up in Edinburgh to mark the life and contributions of a Black person has since disappeared. I’ve conducted several searches for it in and outside of the building over the past few years. To investigate further, I’ve had many conversations with staff members at the Brazilian restaurant Boteco do Brasil that operates from that building to see if they know what might have happened to it. However, I’ve only to meet surprised faces and a dead end on each occasion. There have been many renovations in the past few years, and it’s possible that the plaque was unwittingly destroyed by builders as a result.

As the stories of Black Scots become increasingly known at home, it would be wonderful for us to organise a campaign to have a replacement plaque put up once more in John Edmonstone’s honour. Who’s in?

Catch up with Lisa’s previous blog for us: Edinburgh’s part in the slave trade.

Banner image: John Edmonstone, illustrated by Jacqueline Briggs.

About the author

Lisa Williams is the Director of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association. She runs Black History Walking Tours of Edinburgh and educational workshops in Scottish schools and is Honorary Fellow at Edinburgh University (History, Classics and Archaeology). In addition, Lisa writes a range of non-fiction, fiction and poetry and works as a consultant to heritage organisations across Scotland. You can follower her on Twitter (@edincarib) and Instagram (@caribscot).

Lisa Williams is the Director of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association. She runs Black History Walking Tours of Edinburgh and educational workshops in Scottish schools and is Honorary Fellow at Edinburgh University (History, Classics and Archaeology). In addition, Lisa writes a range of non-fiction, fiction and poetry and works as a consultant to heritage organisations across Scotland. You can follower her on Twitter (@edincarib) and Instagram (@caribscot).