If you think there wasn’t diversity to be found in Scotland’s capital city over 200 years ago, this scandalous court case from Edinburgh’s history might make you think again.

The story begins in Britain’s colonial past when, in the late 1700s, the empire began to increase its influence and hold on the Indian Subcontinent.

The recklessness of youth

In 1793, a young Scot called George Cumming was dispatched to India. George had a reputation as a dandy with a zest for life. George died aged 26, leaving behind a mountain of debt and his two illegitimate, biracial children: Jane and Yorrick.

After their father’s death, the children were sent to school in Kolkata. In 1803, they were separated from their South Asian mother and brought to Scotland. The children were both under 10 years old.

For a while, Jane was sent to a boarding school in Elgin. This was the ancestral homeland of George’s family, the Cumming Gordons.

An engraving showing Elgin in 1718. Get a closer look in Canmore.

New beginnings in the New Town

Jane’s paternal grandmother, the widowed Lady Helen Cumming Gordon made her home at 22 Charlotte Square, Edinburgh. The square had just been built in the fashionable New Town. Lady Helen took Jane out of her apprenticeship to a milliner and asked her to join her household in Edinburgh where she could receive a lady’s education.

22 Charlotte Square is a Category A listed building. Robert Adam, the famed neoclassical architect, designed this Georgian terrace in 1791 and it was constructed between 1803-1807.

In 1810, Jane was enrolled at a fashionable new school at the edge of the New Town. Officially known as the Mrs. Woods and Miss Woods Boarding School, it had been set up in 1809 by an enterprising young woman called Marianne Woods (Miss Woods) and her aunt, Ann Woods (Mrs Woods). It seems that Marianne took the lead in the day-to-day running of the school and that her aunt provided the business sense.

Marianne was just 29 years old when she founded her school. She was soon joined in the enterprise by her close friend, Jane Pirie. Over time, the school would come to be known as the Woods-Pirie or Drumsheugh School.

Location, location, location

The school was on the site of the present-day Drumsheugh Gardens, constructed later in the 1870s and 1880s. This map, held by the National Library of Scotland, provides a fascinating glimpse of the Edinburgh that Jane Cumming, Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie inhabited.

Lady Helen’s house in Charlotte Square was on the boundary of the fledgling New Town. To the west of that, there are open fields and lanes bordered by a handful of buildings. This was the Earl of Moray’s estate. It’s likely that the school was located in one of the buildings shown on this map, courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Within easy reach of the New Town, the school quickly attracted some of the city’s most influential families. The famous painter, Henry Raeburn, was amongst those who sent their wards to the school.

An unwelcome student

Although Lady Helen’s home was within walking distance, Jane was a boarder at the Woods-Pirie school.

Despite being part of a rich, influential and titled family, records indicate Jane was treated harshly by her teachers. It has been suggested that this was because of her race and illegitimacy. It seems Marianne Woods may have softened towards her pupil, but Jane Pirie continued to treat her with severity. A letter from Miss Pirie to Jane Cumming’s aunt hints at the unfavourable treatment that Jane received:

“We never did anything to offend her, excepting too rigidly discharging our duty towards her, and too freely telling her of her faults.”

There were ten boarders at the school, divided between two dormitories. Woods and Pirie also slept in the dormitories, each sharing a bed with a pupil. It seems that the teachers felt that their most troublesome students should be supervised at night and Jane was assigned to Miss Pirie’s bed.

While this arrangement seems shocking by modern-day standards, at the time it was seen as part of the standard care of boarding school children.

The accusation

On Saturday 10 November 1810, Jane paid a visit to her grandmother in Charlotte Square. She divulged to Lady Helen that she had witnessed her same-sex teachers engaging in sexual activity together.

Looking for corroboration of this accusation, Lady Helen sent for Jane’s cousin, who was a day pupil at the same school. The cousin confirmed that she had heard rumours about her teachers at the school, although she had “seen nothing herself”.

The following week, Lady Helen wrote to the school to tell them that she was withdrawing her granddaughters. Lady Helen also dispatched notes to the parents and guardians of other pupils advising them to withdraw their children too.

The rumour mill went into overdrive. All but two pupils were removed from classes and the school quickly collapsed.

Unjustly and cruelly defamed

Before November was out, Lady Jane had been served with a court summons by lawyers working on behalf of Woods and Pirie. It stated that the teachers had been:

“unjustly and cruelly defamed and injured … by means of false, injurious and defamatory allegations and insinuations …[that they] had been guilty of some very improper or criminal conduct.”

The teachers sought compensation of £10,000. No small sum in 1810!

In response to the summons, the Cumming Gordons appointed their own legal team: George Cranstoun and Henry Erskine. Erskine was a big hitter in Scotland’s legal landscape. He had represented Deacon Brodie in 1788. This libel case brought him out of retirement in West Lothian.

Almondell House, where Henry Erskine had been enjoying his retirement. It was demolished in 1969. See more information on Canmore.

The case was heard at the Court of Session in Edinburgh’s Parliament Square. It began on 15 March 1811 and Jane was the star witness for the defence. She testified over a period of four days between 22-25 March, giving evidence alongside other pupils and a servant from the school.

At the time, witnesses were not allowed to testify in court cases involving family members. However, due to Jane’s illegitimacy, she was ultimately cleared to give evidence in the teachers’ case against her grandmother.

Parliament Square, Edinburgh, 1844. Zoom in on Canmore to see more detail.

In her enthralling examination of the case in ‘Scandal And Survival In Nineteenth-century Scotland: The Life Of Jane Cumming’, Frances B. Singh explains that the recording clerk took comprehensive notes, which give a very vivid impression of Jane. From her demeanour as she gave evidence, it seems that Jane may have relished her time in court.

Salacious detail

Throughout the process, Jane was adamant that the teachers had engaged in sexual relations. She explained that she had first become aware of their trysts during the summer, when she had holidayed in Portobello with the teachers. At that time, Jane had shared a bed with both teachers. When they returned to the school, Jane explained that Miss Woods had often visited Miss Pirie in the bed where Pirie and Jane slept.

She reported that she was:

“more often than once disturbed early in the morning . . . they were speaking and kissing and shaking in her bed.”

When pressed for more detail, Jane expanded:

“When Miss Woods came into bed, [she] felt them both take up their shifts and she felt Miss Woods move and shake the bed and Miss Woods was breathing so high and so quick.”

Another (more reluctant) witness in the case was Janet Munro who had been assigned to sleep in Miss Woods’ bed in the second dormitory. She tearfully testified that on at least two occasions Miss Pirie had crept into the bed she shared with Miss Woods:

“I believe her clothes were off and one lay above the other … Miss Pirie was uppermost. The bedclothes tossed about and they seemed to be breathing high. I said: ‘Miss Pirie, I wish you would go away, for I can’t get sleep.’”

Pride and prejudice or unreliable witnesses?

The other witnesses in the case were unable to substantiate Jane and Janet’s claims. They agreed that they were aware of gossip about the teachers but that they had never witnessed anything themselves.

The prosecution adopted a strategy of character assassination as a way to shed doubt on Jane’s credibility. Much was made of her mixed heritage and early childhood in India, painting the schools she attended in Kolkata as “dens of iniquity”. In an assertion revealing of the racism at the heart of colonialism, they also claimed that girls in India reached sexual maturity at an earlier age, due to the climate and culture.

Undermining Jane as a witness was not the only prejudice at play in the judgement. At least one of the judges simply could not believe that two women could have sexual relations. Reflecting on the case, Lord Meadowbank commented that the idea of women having sex was:

“equally imaginary with witchcraft, sorcery or carnal copulation with the devil.”

This denial of lesbian sexuality was not uncommon. Even down to the very records that remain, it’s contributed to the erasure of Scotland’s lesbian history over centuries.

It also seems fairly likely that Jane may have had a crush on Marianne Woods. She was certainly her favourite of the teachers. We know that Jane made a request to sleep in Miss Woods’s bed. Marianne had brushed off these attentions. Did Jane feel jilted when she made her accusations?

A muddled picture

Initially, the judges found in favour of Lady Helen, by a narrow majority of 4-3. But a year later, the teachers appealed and won their appeal by the same slim majority.

Dissatisfied at this outcome, Lady Helen then took a further appeal to the House of Lords, where the scandalous case dragged on until 1819.

Ultimately the Lords found in favour of the teachers and Lady Helen was ordered to pay out. However, after paying enormous legal fees, the teachers did not receive much compensation to make up for nearly a decade of distress and ruined careers.

Jane Pirie remained in Edinburgh in poverty and poor health, unable to find employment. She was also embroiled in a further legal case against her sister. Jane lost her share of an impressive property in Edinburgh’s Old Town that had been left to her by an aunt. She was just coming up to her 54th birthday when she died.

Marianne Woods seems to have fared a little better, although not much. She left Edinburgh for London, where she was able to teach again. She died in a boarding house in Brighton just before her 90th birthday.

From Edinburgh to Elgin

In 1818, Jane Cumming married a minister called William Tulloch. Her new husband has his own scandalous history, charged with “conduct unbecoming a cleric”, which was often a veiled allusion to sexual impropriety. Jane’s family used their influence to have him installed as minister in Dallas, just outside Elgin.

It seems, however, that it was not all “happily ever after” for Jane and William. A letter from a family friend to Jane’s uncle revealed that the couple were involved in a public dispute. Jane had accused her husband of being unfaithful. At this time, it was difficult for unhappy couples to separate and so they continued to live together.

Dallas Church, where Jane’s husband was the minister. Jane Cumming is buried in the kirkyard here.

Truth behind the history books

Was this a case of a vulnerable teenager lashing out with made up stories? Or was there indeed a lesbian affair being conducted within the school by the two school mistresses, dismissed thanks to prejudiced views about homosexuality and the young accuser?

From a distance of 200 years, it’s impossible to determine the truth behind the scandal. However, it gives a fascinating insight into the lives and culture of people who walked Edinburgh’s streets over two centuries ago.

Uncover more

If you enjoyed this blog, you might want to read more about Scotland’s LGBT+ history. We also have a collection of women’s history blogs and blogs on Scotland’s South Asian communities.

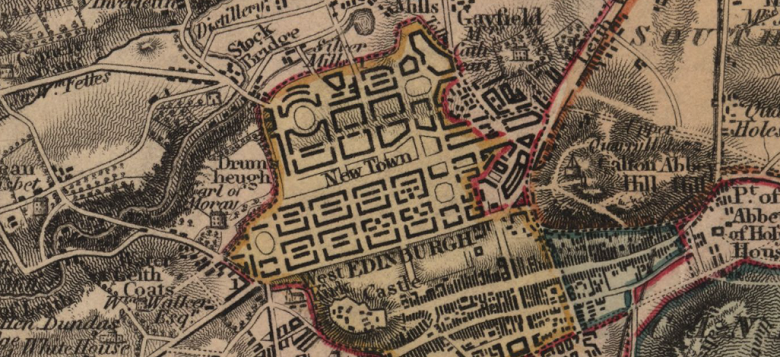

Banner image © Courtesy of HES. Illustration from Modern Athens, T H Shepherd, 1829. Image depicts the Water of Leith.