Luing is the largest of Scotland’s slate islands. It lies a few miles to the south of Oban in Argyll. Like many of the islands on the West Coast, today Luing is considered a fragile one and faces several challenges around island depopulation, economic development, and transport.

During its peak years, the slate industry supported a vibrant island community. The island had a thriving population of over 600 people in the 1800s. There were some 15 historic quarries or workings on the Island of Luing which kept many people employed.

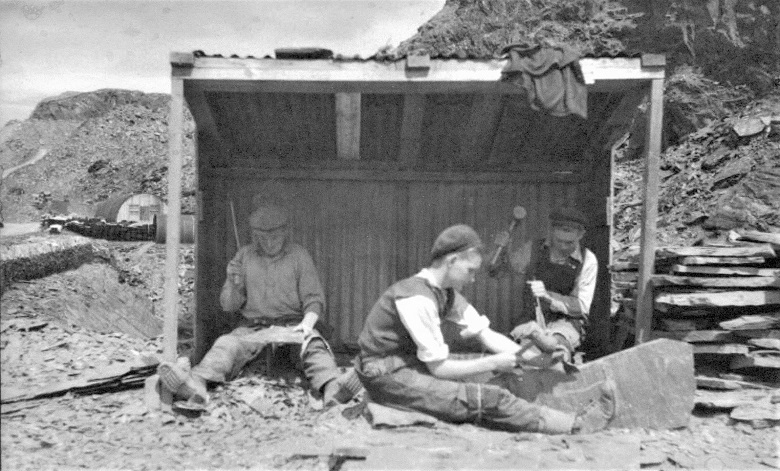

Slate splitting at Cullipool quarry in the 1950s. Image: Luing History Group

The village of Cullipool on the west of the island is a conservation area. Nestled in amongst several historic quarries (which are now flooded), many of the historic quarriers cottage’s roofs and walls remain largely as they looked since they were built.

Cullipool No.5 Quarry, which is in the heart of the village, is now flooded and shows the remnants of a once great industry on the island. Image: Graham Briggs

The slate quarries on the island played an important part of the islands industrial heritage. Slate is used everywhere on the island from walls, paths and roofs. Historically, it played an important role in safeguarding the coastline. It’s even thought that Iona Cathedral is roofed with slate from Luing, which shows just how long lasting Scottish slate is!

A declining industry

Slates and bogie at Cullipool. Image: Gilbert Mackay

Like many of Scotland’s stone industries, slate declined after the first and second World Wars. Faced with a lack of labour, cheaper imported material and a move towards roof tiles, a lack of investment ultimately led to the demise of the slate industry on Luing.

This impacted the rural communities extremely hard. The slate islands relied on this industry to provide employment to sustain the local economy. When the quarries closed in the 1960s, over 24 people who had worked there found themselves having to secure work elsewhere.

The island today is a much quieter place with a community around a quarter of the size of its historic peak of 600 in the late 1800s. The abandoned slate quarries remain a nod to the industrial heritage and landscape that once created a bustling vibrant community.

Island challenges today

The difficulties faced by young people trying to make a life on the island are immense. Finding affordable housing or land to self-build is almost impossible, and the high cost of island living is made worse by the constraints and costs of limited ferry services.

The declining number of working-age people has an impact on island services, making the community less resilient. Making it possible for young people to stay on or move to the island (which many wish to do) is essential for its future.

Storm Aiden at Cullipool in 2019. Image: Colin Buchanan

The island also faces increased risk from climate change impacts through rising sea levels and has faced more frequent storms which have impacted the island shore defences.

Historically, producing slate was an extremely wasteful process and this waste material was used to supplement the beaches. Since no material has been extracted since the 1960s, much of this material has now been washed away, exposing a fragile coastline facing the Atlantic storms.

Cullipool’s slate beach. Slate from the quarries was used to feed the beach, the gradual slope of the slate beach removed energy from the waves which reduced the impact of storms. Today most of the slate material that once fed the beach has been lost with the effect that the village has been impacted by some dramatic storm events. Image: Graham Briggs

A second chance for Scottish slate?

Scottish slate has a particular characteristic look and a skill involved in laying. There is a need for Scottish slate to support the repair of Scotland’s traditional (pre-1919) buildings – many of which are our work places and homes.

“The most critical area in the supply of traditional materials is Scottish slate. No new Scottish slate has been quarried for over 50 years. The lack of a supply of new Scottish slate, and a serious shortage of second-hand Scottish slate, have brought about a crisis. The use of foreign slate is becoming increasingly common, and a new supply of Scottish slate is an immediate priority.”

– Historic Environment Advisory Council for Scotland

Over the last two years, we’ve been supporting The Isle of Luing Community Trust, who have been exploring the opportunities that a small-scale slate enterprise could bring, to create and support good local jobs for people to work and live on the island. It would generate a modest income for the local community to develop other projects, expand the island economy and make it more sustainable.

Establishing a new slate industry would not only create material for our historic built environment, but it could also create material to help the island mange the impacts of climate change and the issue of coastal erosion which threatens the village of Cullipool.

The Isle of Luing Community Trust is now looking for a Project Development Officer to work with them to take the project forward. Apply by Friday 10 June 2022.