In 1560, Scotland’s parliament had made Protestantism the official religion, and morality was high on the agenda. The government and the Church wanted to enforce godliness among the people. They thought that the whole country would suffer if there were malevolent elements within it that they believed to be in league with the Devil. This is the setting in which the Witchcraft Act came into existence.

A pact with the Devil

People believed that the Devil left a mark on his followers when they made a pact with him. So-called ‘witch prickers’ were brought in to prick the accused person with needles numerous times and in intimate places in search of this mark. People believed that the mark would turn the area on the body invulnerable so it couldn’t bleed or feel pain. Often it would have been a birthmark, wart, mole or scar.

© Courtesy of the Trustees of Burns Monument and Burns Cottage. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The aim of the torturous method was to get the accused to give in and confess to the alleged crimes. Other evidence used in trials were neighbours’ testimonies. These could come about after quarrels with other accused witches. They would often name the person that had crossed them as their ‘accomplices’ which could land the troubling neighbour in court as well.

Most of the accused and prosecuted were women. The popular belief was that women were ‘weak willed’ and their intellect inferior to that of men. This supposedly allowed the Devil to influence them more easily.

The Witchcraft Act in practice

Curiously, the Witchcraft Act is brief and does not clarify what a witch is and what constitutes witchcraft. Yet, people were able to identify witches within their communities and bring cases against them.

“…na maner of persoun nor persounis of quhatsumever estate, degre or conditioun thay be of tak upone hand in ony tymes heirefter to use ony maner of witchcraftis, sorsarie or necromancie…”

“…no manner of person or persons of whatsoever estate, degree or condition they be of take upon hand in any time hereafter to use any manner of witchcraft, sorcery or necromancy…”

Most accused witches were ordinary people but the one thing they were thought to have in common was ‘smeddum’ – spirit, mettle, resourcefulness and quarrelsomeness – qualities which went against the ideals of femininity.

A family of witches

In 1597, a whole family was embroiled in a witch hunt. It started with the mother, Johnnet Wischert, who faced accusations of witchcraft by her neighbours, servants and even her son-in-law. The accusations covered decades of believed wrongdoings, misfortune, and even described shapeshifting!

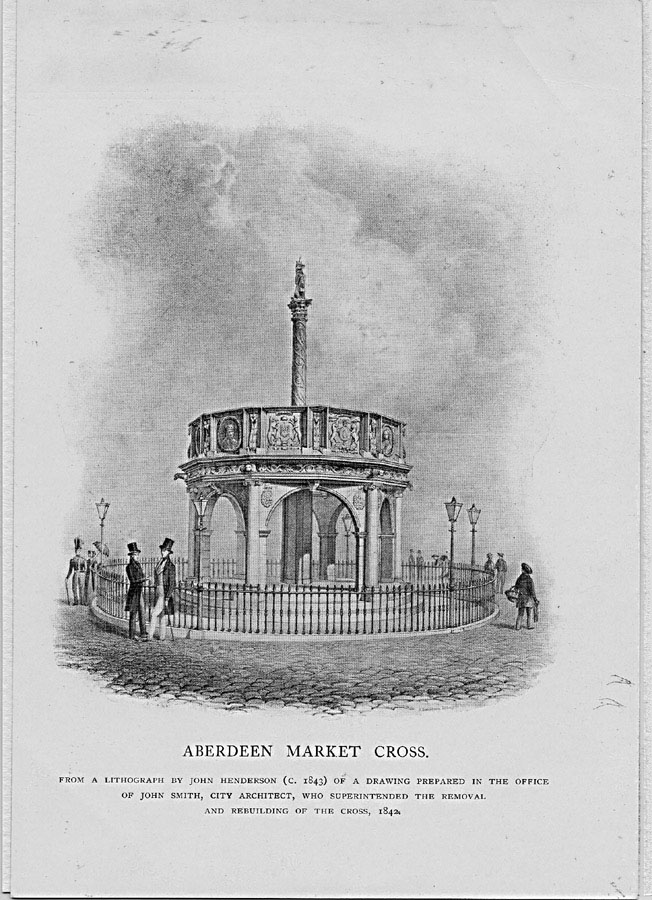

Her son, Thomas Leyis, also faced accusations which focussed on the witches’ sabbath: a gathering of witches in which they worshipped the Devil. Other witches, in their confessions, named him as the leader of a sabbath held at Aberdeen’s Mercat Cross. He was also branded as an active accomplice of his mother, and both were burned.

© Robert Gordon University. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Johnnet’s husband, a stabler called John Leyis, and their three daughters, Elspet, Janet and Violet Leyis, also faced accusations. However, they were only convicted of associating with known witches – namely their own family members – and were banished from Aberdeen.

Why would people confess to practising witchcraft?

Investigators usually tried to get confessions from witches that would prove interaction with the Devil. This was of importance to the court. To get confessions witches were routinely tortured – often with sleep deprivation, but also with physical torture.

In 1616, Elspeth Reoch was tried in Orkney as a witch. For a while, she was mute and suffered beatings from her brother to encourage her to speak again.

In her confession, she claimed to have the ‘second sight’ and to have had interactions with fairies since she was 12 years old. She was found guilty and was consequently executed.

Visiting wells and springs for healing is recorded in kirk session records, which deemed the practice against the teachings of the Protestant Church.

In 1623, an Issobell Haldane confessed that she had gone to the well of Ruthven to fetch water to use to wash a sick child.The child later died and Issobell admitted to consorting with fairies. She was imprisoned and interrogated at the Tolbooth in Perth, convicted of witchcraft and executed.

Innocent until found a witch

Issobell Fergussone, who was married and lived in Newbattle, was pricked by a professional witch pricker in July 1661. She maintained her innocence and denied all accusations against her.

It seems that she asked to be pricked, probably to prove her innocence. However, the witch pricker was successful in finding the Devil’s mark and she subsequently confessed to a pact and interactions with the Devil. She was tried in August 1661 and eventually executed.

The fate of most accused witches is unknown. The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft estimates that about two-thirds were executed. Most witches were strangled and then their dead body was burned.

Only a very small number are known to have been burned alive. But the experience of being interrogated, possibly tortured then executed would still have been extremely invasive, frightening and painful.

Formal repeal of the Witchcraft Act

The last prosecution for witchcraft was in 1727. In Dornoch Janet Horne’s daughter was allegedly “transformed into a pony and shod by the Devil, which made the girl ever after lame both in hands and feet”, and that Janet rode her daughter like a pony.

Both were imprisoned, tried, and condemned, but the daughter escaped. Janet was the last person in the British Isles to be executed for witchcraft.

By the eighteenth century, there was growing scepticism among the authorities about witchcraft, and prosecutions were less likely to result in execution.

Evidence which before had been essential for conviction – including pricking – was now considered unreliable. In 1736 the British parliament repealed both the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 and the parallel English act.

In 2022 Nicola Sturgeon, the first minister, issued an apology for the historic persecution and execution of accused witches, describing it as “injustice on a colossal scale”.

The Church of Scotland then also recognised the terrible harm caused to the thousands of people – mostly women – who had been accused.

About the Authors

Ruth Schieferstein, Nikki Moran and Morvern French work together in the Cultural Resources Team, which researches and interprets the history and archaeology of Historic Environment Scotland’s properties in care. With the increasing attention on Scotland’s history of witchcraft accusations, and the anniversary of the Witchcraft Act on 4 June, we wanted to remember the thousands of people and their lives which the Act impacted.