The Links of Noltland site on Westray is one of the best-preserved and most extensive prehistoric settlements in Scotland. The site, which is severely threatened by erosion has been under investigation since 2006. So far, we have identified over thirty-five buildings including houses, workshops, and a sauna-house together with a cemetery containing the remains of some 105 individuals.

Digging into the Ancient DNA (aDNA)

Photo Graeme Wilson / credit Historic Environment Scotland

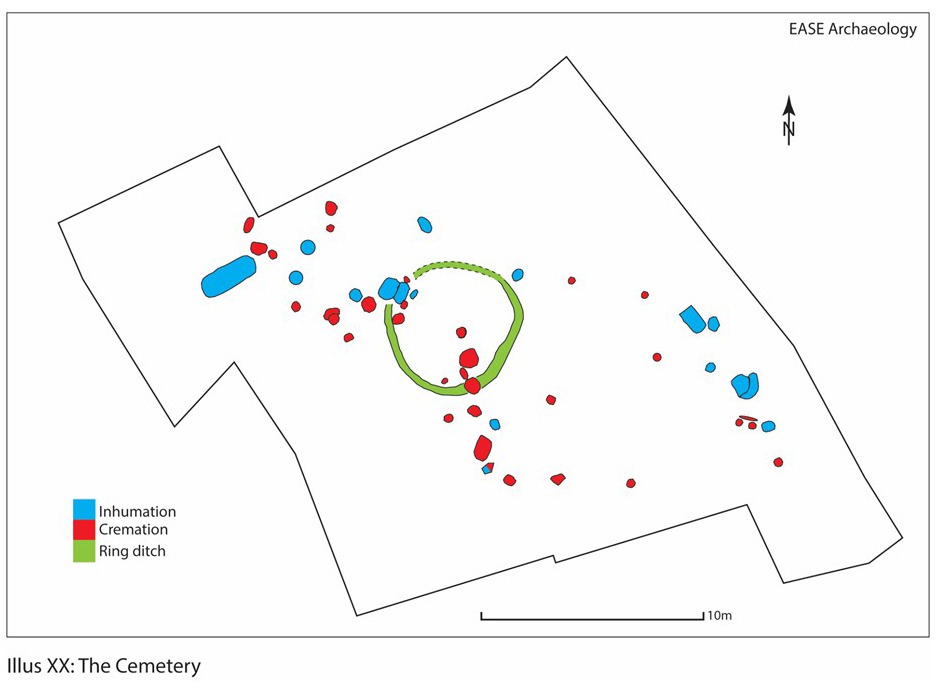

In collaboration with researchers at the University of Huddersfield’s Archaeogenetics Research Group we recently undertook combined genetic and archaeological research. We studied the aDNA data in conjunction with analysis of Noltland’s massive cemetery, containing over 100 varied burials – including a large tomb used as a family vault for centuries.

The genetic findings were recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They show that migration by people with continental ancestry, frequently referred to as the ‘Beaker People’, had spread not only across mainland Britain, but had also reached Orkney. Interestingly, the influx to Noltland was female dominated and this had a unique impact on the site’s genetic makeup. However, in the absence of any distinctive ‘Beaker’ pottery, this influx had been archaeologically invisible in Orkney until now.

Genetic analysis shows the community at Links of Noltland was composed of local males and incoming females of continental descent. The long history of the male lineage indicates males remained and inherited whilst females moved out. This demonstrates not only the fact of immigration but also the way in which it occurred. In other words, the men stayed with the farms while the women married out of the community.

Photo Graeme Wilson / credit Historic Environment Scotland

It appears the men in the Noltland community traced their descent from the original Neolithic population. The lineages of these men persisted for at least another 1000 years. Elsewhere in Britain continental migrants had entirely replaced the existing Neolithic male lineage.

How migration impacted the island

We are continuing to study the site to understand why ancient migration to the island took such a unique trajectory and what impact it had on the Noltland community. Our latest research is published in the journal Antiquity. The results demonstrate how Orkney was taking part in wider networks at a time it was previously thought isolated and undergoing a kind of ‘recession’.

The number of households, apparently remained stable during the Bronze Age, suggesting property was not split between multiple heirs. This impartible inheritance appears to have been a new development, perhaps to ensure that each household had sufficient resources to survive in what were increasingly tough environmental conditions. The evidence indicates the site was slowly becoming inundated with sand, making life more difficult.

During this period new and more complex identities were forged which emphasised ties to the household and the village. These relationships are also evident in the cemetery where many different types of burial were found. New connections with places as far afield as Mainland Scotland and Shetland were also developed. There were new ways to build community and identity, bringing this increasingly diverse population together with shared rituals and activities. This included the use of a steam house or sauna. There was also the adoption of new architecture, technologies and farming techniques.

Together, this blending of new and old ideas appears to have led to a peaceful and productive period. Far from presenting an existential threat, as has sometimes been suggested, the influx of people seems to have coincided with a period of social stability.

Photo Graeme Wilson / credit Historic Environment Scotland

Read more

Biscuits and Cheese? More Than Just a Dig: how an excavation in Orkney inspired a whole community.

A week on Westray: archaeologist Rachel Pickering takes us on a trip to the Links of Noltland excavation site in Orkney.

About the Author

Dr Graeme Wilson is a partner in EASE Archaeology and has worked extensively in Scottish archaeology for more than three decades. His research interests lie in the Northern Isles, coastal erosion, and the archaeology of play.