Halloween is often associated with death and the supernatural. The origins of the holiday we now associate with pumpkin carving (a neep if you’re traditional!) and guising can be traced back to the Celtic pagan festival of ‘Samhain’, a celebration marking the end of harvest season and beginning of the darker half of the year. During this time people believed that the veil between the physical world and the spirit world broke down… So what better time of year to explore some of the historic gravestones cared for by our Collections Team?

Humans have been marking graves for thousands of years. Some of Scotland’s earliest known burial sites are the monumental Neolithic chambered cairns, which housed multiple bodies at once. The use of similar monumental graves such as barrows and cairns continued in to the Pictish period.

Clava Cairns is a complex monument which comprises part of one, if not two, Bronze Age cemeteries.

However throughout most of prehistory, the majority of burials went unmarked, or the grave markers have not survived. There are a small number of Roman gravestones known from Scotland but it wasn’t until the 700s that individual memorials became more common. Like most things in life, the design of gravestones have gone through many different trends. Read on to learn more about some of the different types in our collection…

The Latinus Stone

This grave marker is Scotland’s oldest surviving Christian memorial, dating to around 450AD. It is from Whithorn in Dumfries and Galloway. The crudely carved Roman inscription shows that the stone was commissioned by Latinus and his young daughter. The design includes a ‘Chi-Ro’ – an early symbol for Christ first used during the reign of the Emperor Constantine (c.280AD – 337), whose conversion to Christianity was a key point in the history of the Roman Empire. The stone was later reused as a building material for the walls of Whithorn Priory before being rediscovered in 1890. Whithorn Priory isn’t open to the public right now. Find out more about our high level masonry project.

This small stone is from Iona Abbey. The Isle of Iona played an important role in the history of Christianity in Scotland. St Columba is believed to have travelled from Ireland with 12 companions and founded a monastery here in AD563. The stone is thought to have been carved in the early 600s, soon after the death of Columba. An inscription reading ‘LAPIS ECHODI’ (the stone of Echoid) is carved along the upper edge of the stone. This is probably the name of the person whose grave the stone marked. Could this have been Echodi, King of Dal Riáta, who died in 629? Or the monk Echodi, one of Columba’s original 12 followers?

The St Andrews Sarcophagus

Arguably one of the finest pieces of sculpture from early-medieval Europe, the exact function of the St Andrews Sarcophagus is still debated amongst experts. Dating to the 700s, the piece is comprised of six sandstone panels that slot together. Many believe it to be a Pictish royal sarcophagus (stone coffin) or shrine. ‘Picts’ is the general name used to describe the different groups of people who lived north of the Firth of Forth in the first millennium AD. They had a distinct style of artwork, some of which is included on the sarcophagus, such as hunting scenes and fictional animals. The St Andrews Sarcophagus can be seen at the St Andrews Cathedral museum.

Hogback Stone

Hogback stones originated in Viking England (AD 900s – 1100S) and later spread to Scotland. Their name relates to their distinct shape, which looks like the back of a pig or hog, however it is thought that they were originally created to resemble Viking long-houses.

This example is from Inchcolm Abbey, found on the island of Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth. The stone is carved with a roof tile pattern and animal decorations, both commonly found on these types of stone. Traces of a cross can also be seen carved into one side, suggesting ties with Christianity. Written records from the 1500s describe the hogback once sitting alongside a stone cross in an area of the island used for burials.

The Poltalloch Enclosure

Situated in Kilmartin churchyard, the Poltalloch Enclosure was built in the 1700s as the resting place of the Malcolm family who lived at nearby Poltalloch House. The enclosure houses seven graveslabs. Amongst these are three medieval ‘West Highland’ style stones. These have a tapered shape with intricate scrollwork, interlace designs and carved figures. There are also two medieval effigies of warriors wielding spears and swords.

Effigy of Bishop Archibald

This effigy from Elgin Cathedral is thought to show Archibald, who was Bishop of Moray in 1270 when a devastating fire tore through the cathedral. Archibald used this event as an opportunity to enlarge and enhance the site. Traces of paint remain on the effigy so we know it would once have been brightly coloured. In 2016 Edinburgh Napier University developed a lighting show that gives us a glimpse of what the stone may have looked like when freshly painted.

This carved memorial to a bishop at Elgin Cathedral would once have been brightly painted.

Lynsey Haworth from our Collections Team takes a look at how Scotland has marked its dead in our latest blog https://t.co/omlhpChVAa pic.twitter.com/rBUgpIzMFz

— Historic Environment Scotland (@HistEnvScot) October 31, 2022

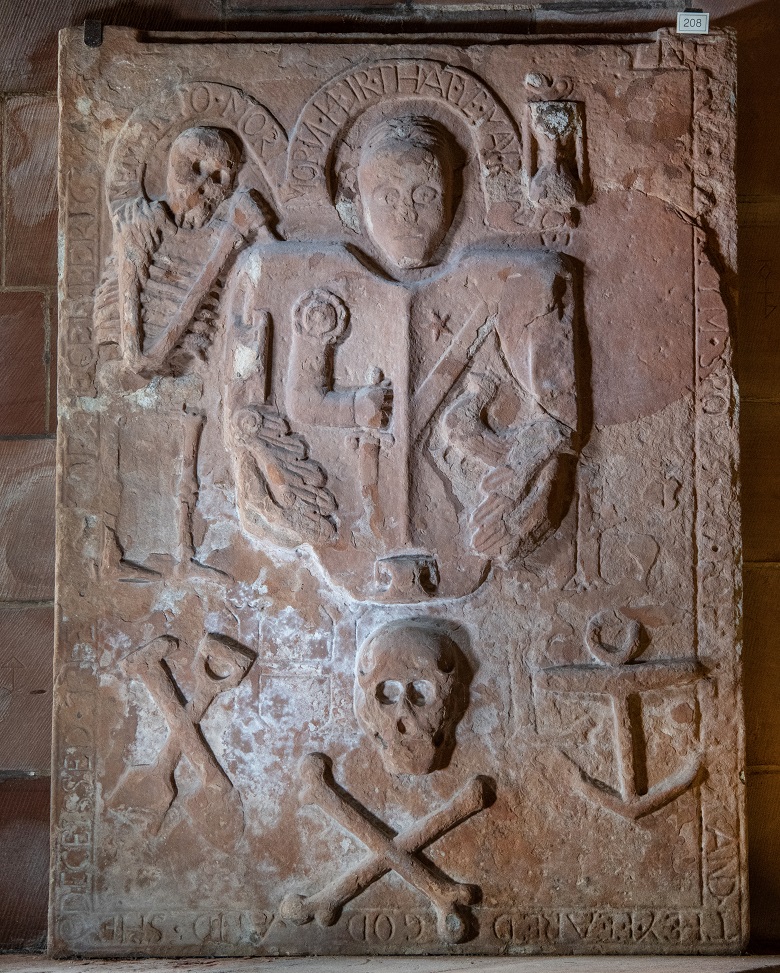

Post Reformation Tomb Slabs

St Andrews Cathedral is home to a number of large tomb slabs that date to the period after the Scottish Reformation of 1560. Much of the collection was carved in the 1600s and the names of those commemorated are still visible on most. These individuals would have been wealthy and important people from the town. Many of these gravestones include designs that show emblems of mortality. These include skeletons (the personification of death) and hour glasses (indicating the passing of time). The Latin phrase Memento Mori (‘remember that you must die’) also frequently appears. The purpose of these was to remind people of the importance of a good life and death.

The Faichney Monument

The tiny chapel at Innerpeffray near Crieff, Perthshire, is home to one of the most astounding and poignant gravestones in Scotland.

The remarkable Faichney monument was carved by mason John Faichney in 1707 after the death of his wife. Individual carvings of ten of their children flank a coat of arms, which is located below a large depiction of the couple.

Explore our collections

If you’ve enjoyed this tour of the gravestones in our care, why not uncover more fascinating stories from our collections on the blog.