From the outside, Skelmorlie Aisle in Largs looks very unassuming. However, its rather plain exterior masks a spectacular interior.

Built in 1636 as an addition to Largs Parish Church, Skelmorlie Aisle was the private place of worship and resting place of Sir Robert Montgomerie of Skelmorlie and his wife, Dame Margaret Douglas.

Skelmorlie Aisle in Largs.

Its ornate interior has no parallel in Scotland. It’s in two parts: a private gallery for the exclusive use of the laird and his family (known as a laird’s loft) and a vault.

The monumental stone tomb in the laird’s loft is carved in the Renaissance style, which began in Italy in the 1400s. It was probably carved by Scottish masons using foreign pattern books and may have originally been richly coloured.

The vault, normally not accessible to the public, still contains the lead coffins of Sir Robert and Dame Margaret.

But today, we’re here to talk about the glorious ceiling at Skelmorlie Aisle and how it inspired a recent project to investigate the use of modern sustainable materials.

Look up!

If you cast your eyes upward in this small building, you will discover a richly painted ceiling.

It was painted in 1638 by the artist J Stalker, who had also done work in Edinburgh Castle and Parliament House.

This splendid ceiling is an incredibly rare example in Scotland. It was painted in the wake of the Scottish Reformation. Many works of art with religious themes were destroyed during the Reformation, and in the 17th century it was incredibly rare for new works of religious art to be commissioned. It is also the only known ‘early’ painted ceiling existing in Scotland which has an artist’s signature.

We’re very lucky that experts in the history of Scottish decorative painting, Michael Bath and Angela Callaghan, have produced extensive research on the topic of the Skelmorlie Aisle ceiling. If you’d like to find out more about the composition and symbolism of the ceiling, and the site in general, please download our Statement of Significance for Skelmorlie Aisle.

The ceiling is composed of forty-one individual compartments. Each one contains different combinations of emblems, designs, human figures, animals, birds and heraldic representations. Of the forty-one compartments, four contain landscape paintings, depicting the seasons, and their associated labours.

Pandemic project

Back in 2020, when the pandemic meant we couldn’t carry out our usual conservation work, I had time to work on something a bit different – a reconstruction of one of the works in our care.

I had been part of the staff group working on ‘Climate Ready HES’, our organisation’s first climate change adaptation plan. Themes of the climate crisis were at the forefront of my mind!

My challenge was to recreate an image from our collections, using sustainable materials, which also conveyed a message about climate change.

A suitable subject

It was the Skelmorlie Aisle panel depicting ‘Winter’ which caught my eye. Flooding, storm surges and coastal erosion can all be seen in the 384-year-old panel. All of these would have been familiar to previous generations but with climate change resulting from human emissions and activities, the frequency and severity of these are increasing rapidly.

The ‘Winter’ panel

If you take a close look at the panel, you’ll see a frozen river in the centre, dividing the composition. People are seen skating in the foreground and a ship is frozen in on the left. On the right stands a thatched cottage with two people in front of the door. One woman holds a pan which contains ice and the other a red-hot poker to melt it. Her act of melting the ice is thought to be a visual metaphor for meltwater from snow and ice causing floods. On the right of the scene, you can see a submerged farm building. You can take a very close look over on Canmore, using the zoom feature.

On the right of the composition is a wild sea. Ridges of ‘white horses’ engulf two sailing ships while a third one has already succumbed to the storm.

This scene depicts Largs. The river is the Gogo Water, which flows through the centre of the town. The church tower is Largs Parish Church, which was demolished in 1812. The building with the crow-stepped roof beside the church tower could be Skelmorlie Aisle itself.

Stalking J Stalker

To understand how to recreate this panel, I had to find out about the materials and techniques used by Stalker. Thankfully, my colleague Damiana Magris and University of Northumbria at Newcastle had carried out previous investigations into the materials used, so I was able to use their findings in my project.

Unusually for this period of decoration in Scotland, the ceiling is painted in oils rather than a water-based paint. The decoration is pained on to timber.

Finding a base

I set myself up in a north-facing room. This cool, indirect light is the perfect condition for an artist’s studio and I didn’t have to rely on electric light. And working from home, like so many of us did during the pandemic, meant there were no travel emissions!

I sourced the timber base for this project locally. The original ceiling is made of pine, which is prone to warping. I opted to use a modern alternative: a Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) plyboard. This is a composite timber with pine incorporated. FSC approved products promote the sustainable use, conservation, restoration, responsible management and development of forests.

I drove to collect the timber but combined my journey with other errands to get the most out of the carbon footprint for this travel.

Preparing the surface

In order to prepare the timber surface for painting, it needs to be coated in several preparation layers. Firstly, the timber must be sealed. Traditionally, this is done with glue made from rabbit skin. For centuries rabbit skin glue has been used by artists and conservators alike as a base for painting and as an adhesive. The glue is considered a by-product of the meat industry, with over 50% of the product originating from China. An argument could be made that this is a sustainable use of a waste product. However, there are valid concerns about the ethical nature of the product. Rabbits farmed for meat and fur are often kept in barren, overcrowded conditions.

Top left image shows the soaking of the glue size. Top right shows the sifting of the gesso. Bottom left shows application of the warm gesso layers. Bottom right shows the prepared panel.

A commonly used alternative is an acrylic-based base. However, as a plastic-based product this also has its drawbacks. Sometimes there isn’t a perfect alternative and compromises have to be made. In the world of conservation practitioners are in the early stages of developing Life Cycle Assessments to help us make more informed decisions and balance the pros and cons.

For this project, I used my remaining stock of rabbit skin glue, but in future I will look for ethical and environmentally friendly substitutes.

After sealing the panel with glue, I applied gesso. This is a primer that the paint will adhere to.

Sketching the design

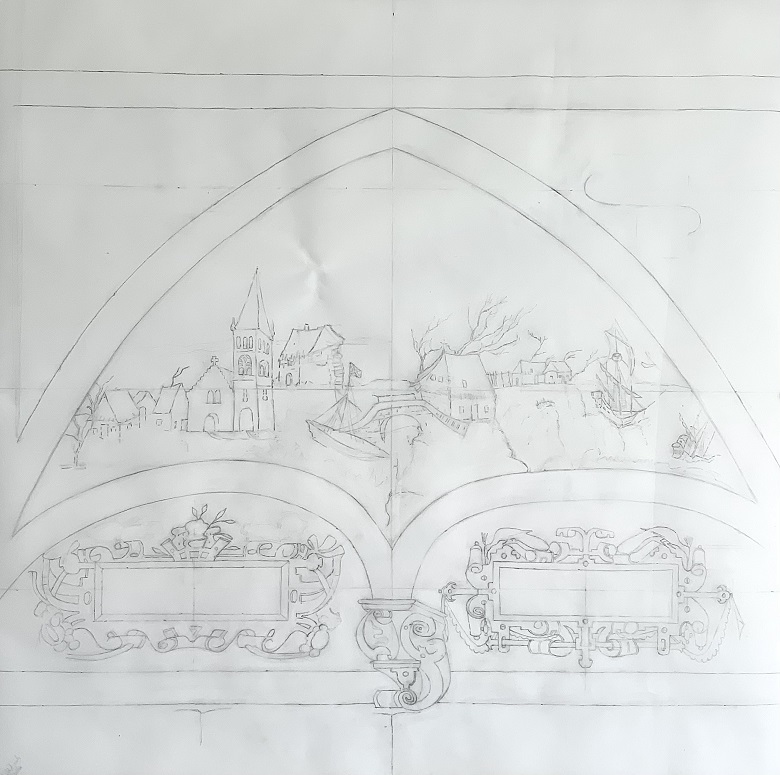

I then made a free-hand line drawing of the scene on biodegradable tracing paper.

The preparatory sketch of the design.

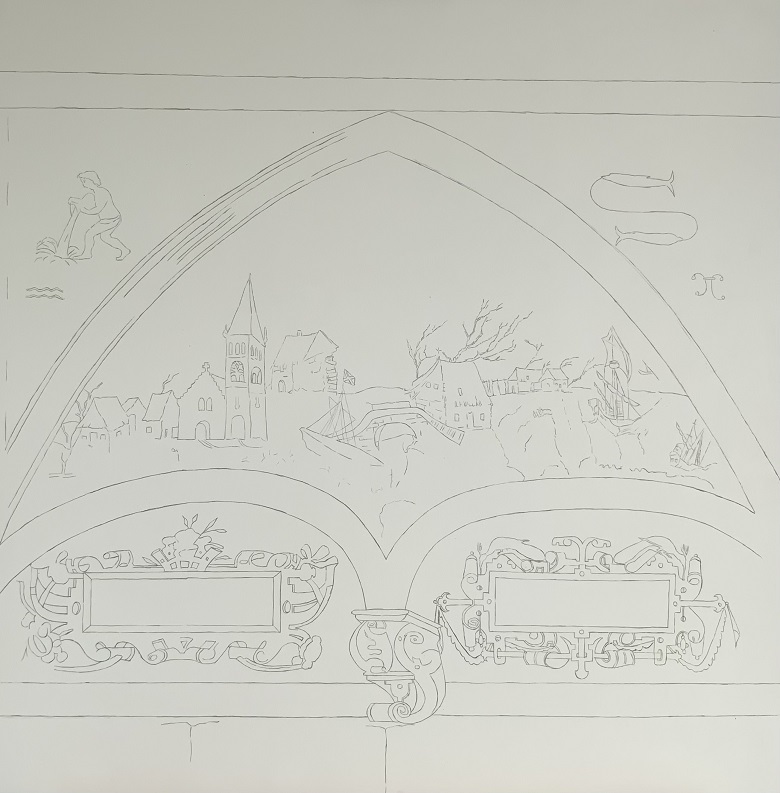

Once the design was complete, I transferred it on to the prepared wooden panel. The main design outlines were ‘fixed’ with black Indian Ink.

The design fixed in Indian Ink.

I used solid graphite pencils to sketch the preparatory design. These are more sustainable as they don’t use wood. However, wooden pencils can be used more sustainably. Pencils are usually made of cedar wood which can act as a pest deterrent, so you could use they shavings as mulch in the garden! Graphite is also safe to use in compost and mulch.

Painting

This was a challenging stage where it wasn’t always easy to balance the aims of this project. I was keen to use more sympathetic materials but to also reflect those originally used in the creation of the Skelmorlie ceiling.

Various painting materials considered for their non-toxic, sustainable or ethical qualities.

When it came to paints, I decided to substitute traditional oil paints with water mixable oils. I also chose to replace animal hair brushes with synthetic brushes. Again, this was one of those tricky judgement calls between the welfare of animals and a plastic-based alternative.

Painting of the reconstruction in progress.

When sourcing the materials, I researched different suppliers and selected them based on their ethics and sustainable standards. For example, in Stalker’s original artwork he would have used a lead-based white, which we now know to be toxic. I used a titanium white instead.

What I’ve learned

Throughout this journey of exploration into more sustainable and ethical working practices, difficult decisions were made to adapt. I was certainly venturing out of my comfort-zone in abandoning the use of some well-loved traditional materials. This was an exciting opportunity to explore changing practices.

Often it’s only when you try and undertake something practical that you begin to thoroughly examine all the aspects and interrogating previous practices. Just bringing up the questions helps to raise awareness and allow for further considerations in the future. Striving to become more sustainable is a journey that can tie you in knots but can’t be ignored and hopefully every little helps.

The finished reconstruction.

About the author

Ailsa Murray is a senior paintings conservator within the Applied Conservation Team at Historic Environment Scotland. She looks after easel paintings (portable paintings) and also structural paintings, like murals and painted ceilings. Her remit covers a very wide range of work; from medieval wallpaintings to 20thC paintings on canvas. Ailsa cares for paintings in the Central and Edinburgh areas.

Find out more

Uncover more stories from our Conservation Team.

Please note, Skelmorlie Aisle is closed over the winter months but will reopen in spring.