Whether it’s the latest adaptation of an M.R. James classic or folklore that’s been passed down through generations, there’s nothing like a cosy Christmas night for a telling a chilling tale. The Wraith at Fort George is exactly that.

Historic editions of Cabar Feidh form part of the extensive collections at The Highlander’s Museum at Fort George. The Queen’s Own Highlanders (Seaforth & Camerons) Regimental Trust have kindly given us permission to reproduce The Wraith below. Snuggle up and get ready enter the fort on the eve of the First World War…

The Wraith at Fort George

(By W. Kirk, Author of Stories of Second Sight in a Highland Regiment)

I am going to call the man Spence, Kenneth Spence, although he was as pure Highland in blood as any Mac who ever wore the Mackenziue Tartan.

It was at the Fort then that I met my friend for the first time. He was a splendid type; a giant who had never heard of self-appraisement, a man with every gift of personal perfection the gods can bestow, but as modest as a medicant friar. We would sit yarning for hours at night, glad to be free of a somewhat noisy company, mostly gracing the canteen at these times.

He would tell me much of his home life in the West, and he was never tired of talking of his mother, whom he worshipped. She was not strong – some heart trouble, he said – and dwelling on her weakness caused him great unease. Often I would hear a very terror in his voice when he spoke of this thing. He would not be rallied, nor would it have been any kindness on my part to try to cheer him by means which might apply to a character less singular.

One night he told me the story of the family wraith – “Mac’s banner”, as he called it. An old strange story of the historical Highlands it was to me, but these are traditions at which no man but a fool could laugh.

The incident happened before the dawn of written histories. It had been handed down through the years, this tale of the Lady’s Veil. She was a bride newly come to the family stronghold, which was a grim keep in the centre of a loch.

Affairs of the Clan held her Chieftain engaged in the morning, and during such hours she would take a boat, and, alone, explore the loch islands, of which there were many. Like all lakes in the mountainous districts, this one was subject to sudden squalls, but the lady laughed at risks. One day, however, her boat was caught in such a sudden storm.

A scream of terror penetrated to the room in which the Chieftain was dispensing justice. The terror-stricken man rushed to the window overlooking the loch in time to see the death of his bride. The wind had whipped the silken veil from her head, and the vagaries of the storm had carried it and wrapped it round the protruding head and shoulders of the Chieftain as he watched the death struggle.

A day or two after – the month was March – towards the close of a very tempestuous evening, Kenneth and I repaired to the Ramparts. The barrack-room was dark and none too warm. In the open we can walk and talk and smoke. We stood a while at an embrasure and watched the scene, dreich and lonely in the last degree.

The wind came out of the North-East in strong gusts, a grey and ghostly light showed still in the remote West, but the hills and the darkened sea were one in their sameness. From the East came the inexpressibly sad and mad moaning of the buoy on Nairn Sands, a sound in itself fearsome and disturbing. The loneliness of the sea was broken only by the passage of solitary gulls, crying forlornly in the gloom.

There are natures that find something soothing in surroundings like these, something akin to the hidden deeps in themselves. The true Gael always responds to influences of place and weather. We stood there silently in the dark, not a sound reached us from the hive of humanity below us.

I believe I was the first to see it. At the moment, Kenneth was gazing eastwards, absorbed in, God knows, what sad thoughts of his own. For the second I hesitated. Some instinct told me that here was coming something uncanny, something foreign to the ordinary experiences of men. It was like a widespread sheet of whitest linen, and it was beating towards us, fluttering and swaying in the face of the wind!

Perhaps I cried out. I cannot remember now after twenty years.

“God!”

I heard his voice, strangled by some emotion beyond my explaining. And then again –

the Veil, the Veil!

And the he dropped into my arms, a strong man helpless as a child. I propped him against the wall, and held him there. By now the thing was on us, like a gauze of finest cobweb it clung to out heads, and wrapped our shoulders round. It felt horribly wet and cold and clammy. It clung onto our hands and faces, leaving a salt taste on the lips as if we had been drenched in spin-drift. I dropped Kenneth’s form to the ground, but still it clung, a nauseating cloud of horror between us.

Now Kenneth raised his head and I bent down to raise him to his feet. It was done, and the thing was gone; passed into the mystery out of which it came. He was in a state bordering on panic, but he knew.

“My mother is dead.”

We passed below, down to the friendly haunts of men. And we got to our cots in silence. Something had happened, that must not be spoken of in a barrack-room.

Morning came with its proof. Kenneth went away to bury his mother, and I went on to Cromarty. He had not come to the 3rd Battalion by the time I left with the draft, nor have I ever seen him since.

Looking back on that time, I often wonder if it was some sort of personal hallucination. Did Kenneth Spence ever exist? Why did he not join us? No man at the Fort at that time, and I met many of them in France, could ever remember him. One fellow went too far.

“So,” he answered my enquiry, “that was the name o’ your pal. But you were the only one that ever saw him. We others knew damn well you were puggled.”*

But I was not!

*A Scots word used for weariness, exhaution – or drunkenness

Visit Fort George and The Highlander’s Musuem

So, what do you make of our tall tale? Did the legend of the wraith make a return on the remote ramparts? Or was our narrator’s imagination running wild? Anyway, fear not – you’re much more likely to spot a dolphin from the battlements!

You can discover more about the soldiers who have been stationed at Fort George since the 1700s at The Highlander’s Museum. The museum showcases the history of the Highland Regiments, with an array of artefacts and archives. Admission is included in a visit to Fort George.

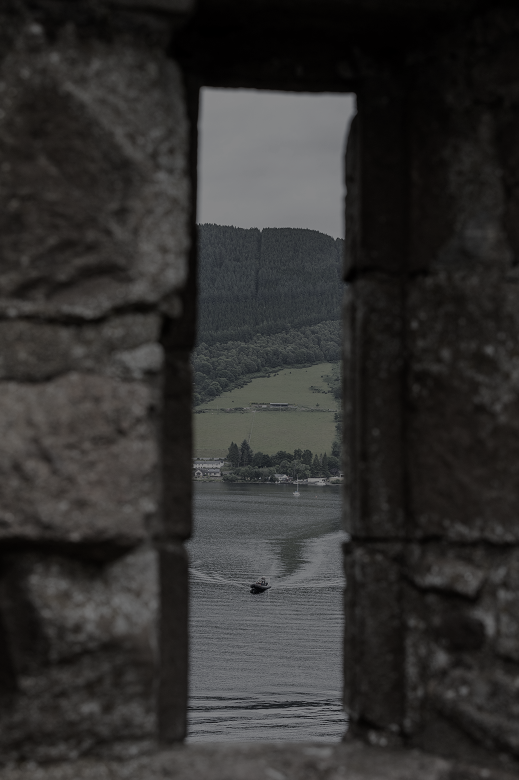

The black and white photographs of Fort George which we’ve used in this blog were taken in 1958 and can be viewed on Canmore along with many other archive images. Castle Stalker, on Loch Laich, is standing in as the “grim keep in the centre of a loch”. The view through the castle window is from Urquhart Castle.

This is the final blog in our series published for Scotland’s Year of Stories, but you can look back on them all in our blog archive. And for more frights and sights, check out our Ghostly Stories for Halloween.