In the Master’s Room of Trinity House in Leith, you will find three wooden bookcases. Over 500 books sit on these shelves, with countless stories held between their pages.

Amongst the many volumes detailing tales of historic voyages, tips for sailors and histories of Leith, three key stories stood out.

These stories uncover Scotland’s links to the Transatlantic Slave Trade, connected to Trinity House and the port of Leith.

Oil on canvas of ‘A view of Leith with Galleon’, Trinity House.

The Darien Scheme

Did you know that Scotland attempted to set up its own colony in 1698? Inspired by England’s colonial wealth and power, the Company of Scotland was set up in 1695. Later, it became known as the Scottish Darien Company.

The first expedition was planned to create a settlement in Darien, Panama with the intention of trafficking enslaved Africans to undertake forced labour in the gold mines of Panama.

The failure of Scotland’s colony

The book ‘The Disaster of Darien’ describes the set-up and downfall of the Darien Scheme.

‘The Disaster of Darien’ from 1929 by Francis Russell Hart, is one of the books on the shelves in the Master’s Room at Trinity House

In July 1698, three years after the establishment of the Company of Scotland, and with huge investment from the people of Scotland (estimated at almost half of the national capital!), a fleet of ships set sail from Leith, heading for Darien.

However, the problems started right away. Their supplies of food were “badly chosen, ill-balanced, and the quantities of many things so much less than the needed amounts”. Forty-four died on the journey.

Their issues continued once they made it to land. Many fell ill. And the hostility from the neighbouring English colonies and an attack by Spaniards were a constant threat.

© Glasgow University Library. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Under a year after setting off from Leith, the settlement was abandoned. Subsequent fleets arriving found a deserted colony and demolished port.

Of the sixteen ships that set sail from Leith in three separate fleets, only one ship returned to Scotland. Two thousand people died, and the Scottish economy was devastated.

With a need to rebuild the economy, and the desire to benefit from colonial endeavors, the failure of the Darien Scheme became “one of the most important factors in hastening the Union of Scotland and England”. The Act of Union was agreed in 1707.

The Pirate John Paul Jones

Exploring the history of Leith through books including ‘Leith and its Antiquities’ by James Campbell, and ‘Studies in Naval History’ by John Knox Laughton, one man’s name came up again and again.

You’ve heard o’ Paul Jones, have you not, have you not?

And you’ve heard o’ Paul Jones, have you not?

How he came to Leith Pier, and fill’d the folks wi’ fear,

And he fill’d the folks wi’ fear, did he not, did he not?

And he fill’d the folks wi’ fear, did he not?

The name John Paul Jones might not ring any bells, but in 1779 in Leith, it would have put fear in your heart. Born in Kirkcudbrightshire in 1747, he first went to sea aged thirteen. At seventeen, he started working on ships in the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

John Paul Jones. Trinity House holds several stories about the Scottish-born American naval lieutenant © Hulton Getty. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

He worked as a third mate on the ‘King George’, then a first mate on the ‘Two Friends‘. Allegedly, he left these roles due to “disgust at the cruelties and horrors” of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. However, Laughton writes in ‘Studies in Naval History’ that there is “simply no evidence as to the cause of his leaving the ‘Two Friends'”. He suggests that the tropical climate on the coast of Africa might have taken a toll on Jones’ health.

Why did Leith fear John Paul Jones?

With the escalation towards the American Revolution, in 1775, John Paul Jones became the first lieutenant in the newly formed American navy and began naval warfare.

In Britain, he became known as “Paul Jones, pirate, or United States naval commander – just as one is pleased to regard him”. In 1779, he made his way to Leith.

“I formed an expedition against Leith, which I proposed to lay under contribution, or otherwise reduce it to ashes” – John Paul Jones

He was confident that he would succeed and wrote a summons to address to the Magistrates of Leith. He demanded a “contribution towards the reimbursement which Britain owes to the much injured citizens of the United States”. However, bad weather thwarted his plans and pushed his ship, ‘Bonhomme Richard’, out of the Firth of Forth. This close-call led to the construction of Leith Fort.

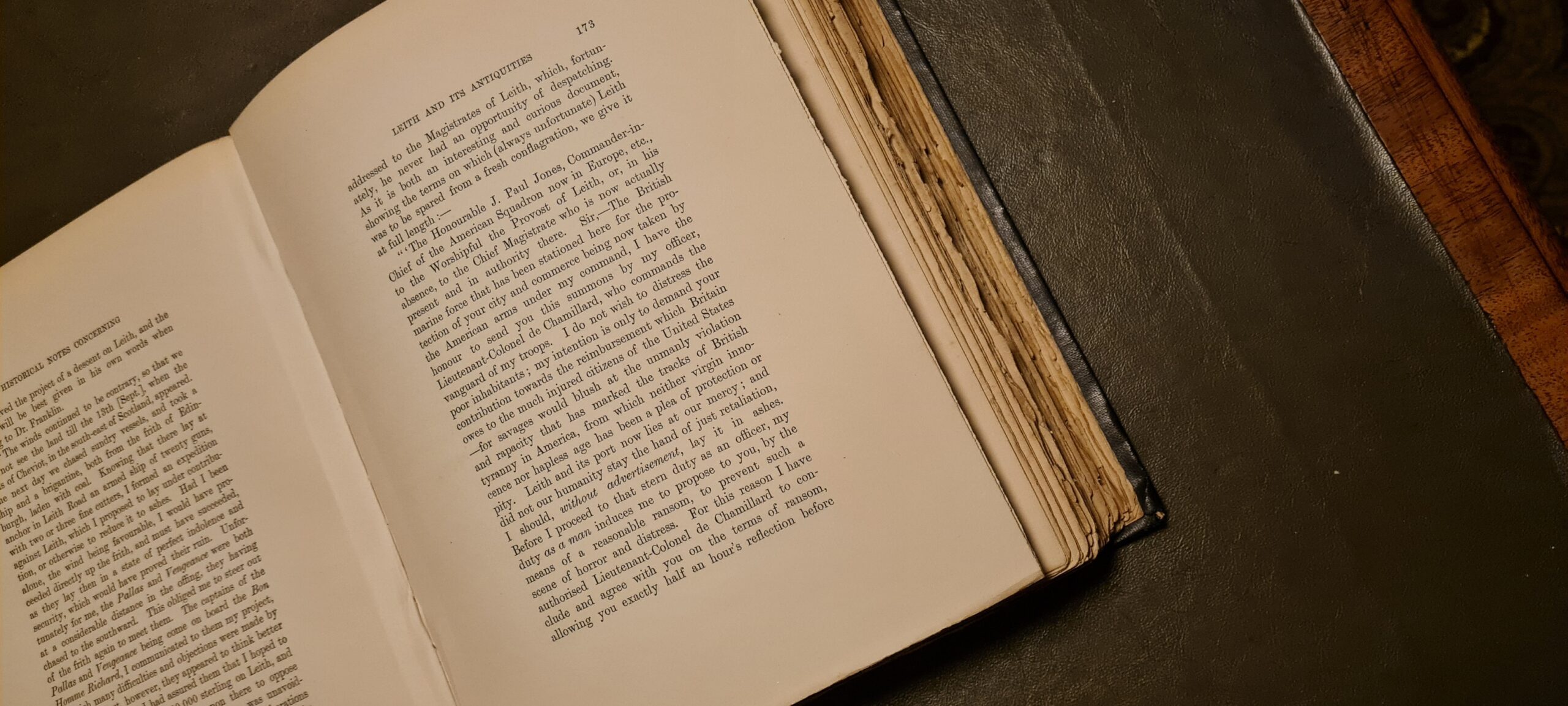

The Book ‘Leith and its Antiquities’ by James Campbell at Trinity House. It features John Paul Jones’ address to the Magistrates of Leith. Content warning: The text uses the offensive term “savages” to describe people regarded as less civilised.

The HMS Bounty

Although not a Scottish endeavor, the collection at Trinity House holds a ship model of the HMS Bounty.

Model of the HMS Bounty at Trinity House

More than half a dozen books in the Trinity House bookcases describe the events of the HMS Bounty.

In ‘The Sea: Narratives of Adventure and Shipwreck, Tales and Sketches’ by W. & R. Chambers, the purpose of the first (and last) journey of the HMS Bounty is described: “the object of the present expedition was to convey from Otaheite [Tahiti] to our West Indies colonies the plants of the bread-fruit tree, which Dampier, Cook, and other voyagers, had observed to grow with the most prolific luxuriance in the South Sea islands”.

Breadfruit, a large starchy fruit, was an easy crop, intended as a source of cheap food for enslaved Africans undertaking forced labour in the Caribbean.

Mutiny on the Bounty

The HMS Bounty set sail in December 1787, arriving in Tahiti in October 1788. Over the following five months, the crew collected and prepared breadfruit plants for transportation. The ship and its crew set sail for the Caribbean on 4 April 1789. Mere weeks later, a mutiny broke out on the ship.

In a log written by the commander of the ship, William Bligh describes how “just before sun-rising, while I was yet asleep, Mr. Christian, with the master at arms, gunner’s mate, and Thomas Burkit, seaman, came into my cabin, and seizing me, tied my hands with a cord behind my back, threatening me with instant death”.

Some have suggested that the crew were angry to have been forced away from Tahiti and the Tahitian women, while W. & R. Chambers wrote that the mutiny “resulted entirely from the commander’s giving way to one of those furious and ungovernable fits of passion”. There is no suggestion of qualms at the transportation of the breadfruit, and the enslaved people it was proposed to feed.

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

In the aftermath of the mutiny, Bligh returned to Britain with those who remained loyal to him. The mutineers returned to Tahiti and some continued their journey to Pitcairn Island. The British Navy found the mutineers who returned to Tahiti in 1790. The survivors returned to England for trial. Those who settled on Pitcairn Island remained undiscovered until 1808.

The End?

This research into the bookcases at Trinity House is part of an ongoing project at Historic Environment Scotland. The project looks into previously underrepresented stories.

These stories, from the Darien Scheme in the 1690s, to the journey of the HMS Bounty in the 1780s, highlight just a few aspects of history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Its legacies continue to impact society today.

In the past months, the city of Edinburgh (which Leith has been part of since 1920) formally apologised for the city’s role in colonialism and slavery: understanding these histories is vital to move forward.

About the author

Tessa is studying for her Master’s degree in Socially Engaged Practice in Museums and Galleries at the University of Leicester. This included an eight-week research placement with Historic Environment Scotland between October – December 2022. Alongside her studies, she works in Learning and she is passionate about facilitating meaningful engagement with heritage.