Princes Street in Edinburgh is one of Scotland’s most iconic thoroughfares. It’s a favourite haunt of locals and tourists alike. Edinburgh’s main commercial street runs along the southern perimeter of the New Town Conservation Area. The north side of the street is home to 43 buildings and a statue listed as nationally important.

A sounding board

Although planning permission is granted or refused by the local authority planning departments and not by us, we’re often consulted by local authorities on planning proposals that they think are particularly important. This is usually in relation to plans for Category A or B listed buildings. You can find out about our role in the Scottish planning system.

It’s no surprise, then, that over the past few years, the City of Edinburgh Council has asked for our advice on proposals to change, extend, reuse, and refurbish many of Princes Street’s iconic landmark buildings.

We’re always happy to provide our view on a listed building consent application. Our experts ensure that the cultural significance of the buildings is understood and provide our own assessment on the impact of proposals to alter, extend and change these buildings.

The march of time

Princes Street has always changed. Over the decades and centuries buildings have altered and adapted for new uses. In many instances, the desire for bigger hotels, retail and commercial buildings resulted in the demolition of smaller buildings.

Today, Princes Street has many layers of change following each generation. The street started out as planned terraces of townhouses and tenements for the wealthy New Town residents. This was outlined in the 1767 plan by James Craig.

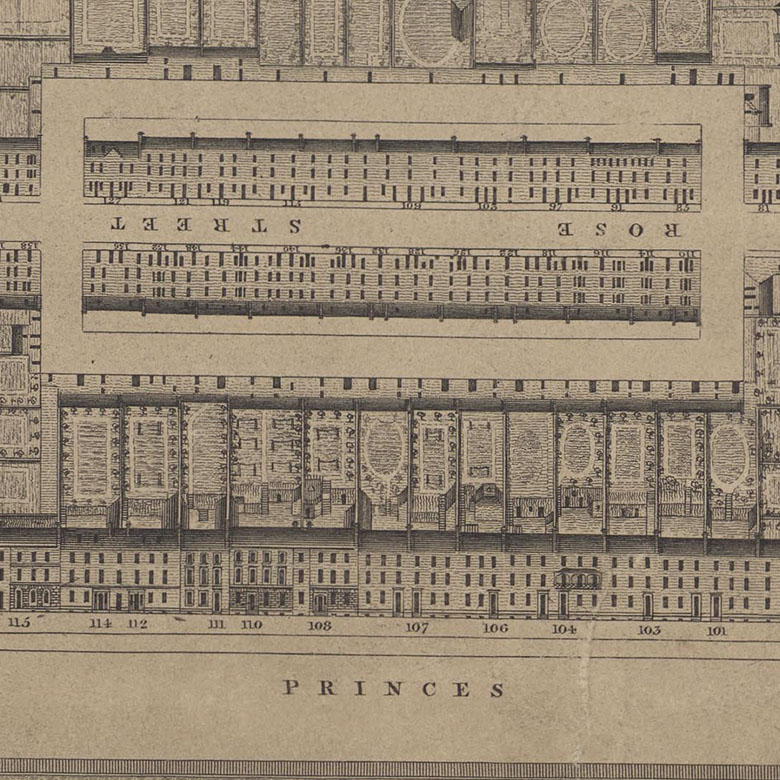

This 1819 map by Robert Kirkwood shows the Georgian elevations of Princes Street’s buildings and their gardens behind. Explore the map in more detail. ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’ (Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Very few of these remain and have been heavily altered at ground and first floor level. However, you may spot the original townhouse frontage at the upper levels if you look up.

Look up to see Georgian townhouses lurking behind later additions to the street level on Princes Street. ©HES

By the 1820s, the buildings had already started to change. Businesses began knocking through or altering the original structures to make shops and hotels.

During the Victorian period, many townhouses were heavily altered and extended. Bay windows, extra storeys, and front extensions to the ground and first floors were all popular additions. In some cases, the Georgian buildings were demolished entirely. An example of this is the former ‘Clarendon Hotel’ at 104-106 Princes Street. This was a large, purpose-built hotel which until recently housed Zara.

Are you being served?

Both Victorian and the Edwardian periods saw the introduction of huge department stores, such as RW Forsyth which went on to become Topshop/Topman, and Jenners. This new era of consumption led to the building of towering architecture and elaborately-carved stonework built to impress wealthy consumers.

Forsyth’s impressive and large building on the left. ©HES

In fact, Forsyth’s department store replaced the short-lived Richmond Hotel, which was demolished after only being there for 15 years! This shows the impressively quick commercial turn-over of these spaces. In addition, there were also buildings built for others uses, like tearooms, member’s clubs, insurance company offices, banks, and the Picture Theatre.

Princes Street meets the modern age

In the post-war era, modernist architecture combined with urban planning ideas that Edinburgh should be transformed to meet the expectations of the future, and the demands of increased car ownership.

In 1954, a panel of influential architects and town planners was formed to investigate how the street could be improved. Reporting back in 1967, this group felt the street looked messy with buildings of such varied heights and styles. Their plans would have seen most of the buildings on Princes Street demolished and replaced with new buildings designed to a unifying set of standards. Only three of the original buildings would have escaped demolition, according to their designs.

A 1965 design for the Members’ Lounge at The New Club (84-7 Princes Street). © HES (Reiach and Hall Collection).

This future-ready plan included putting a motorway along Princes Street, with a pedestrian walkway above. Of course none of this ultimately went ahead. However, there are several buildings with surviving key ‘Princes Street Panel’ features designed to fit into this future plan.

Boots (101-103 Princes Street) and the former British Home Stores building (64 Princes Street) are examples of buildings which feature a cantilevered overhang that would have connected to the elevated walkway at first floor.

The BHS building, which incorporates idea from the ‘Princes Street Panel’ with it first floor balcony. © HES

The opposite of a facelift

During this period there were also many cases where buildings were substantially rebuilt with only the frontage remaining. This can be seen in photographs of the former Conservative Club (112 Princes Street) being converted into the new Debenhams store (1978-81).

The building at 112 Princes Street is currently due to find a new mixed use as a hotel, spa, restaurant, with retail on the ground floor. The historic frontage to Princes Street will once again be retained, carrying on this particular architectural tradition.

Ringing the changes

These proposals for the former Debenhams reflect the next generation of change, both within our society and along Princes Street. The growth of online shopping and pandemic impact of more home working and less public commuting to the city centre, has caused many shops to close or move. This, coupled with the opening of the new St James Quarter shopping centre, has resulted in many big-name high street shops relocating and leaving empty premises behind on Princes Street.

Plans afoot

While there are some temporary shops using these units, many buildings are now being processed through the planning system. Most of the plans involve converting the buildings for mixed use: namely hotels with bars and restaurants at street level.

We welcome sustainable reuse of Scotland’s historic buildings. The greenest building is one which already exists. Furthermore, they are likely to result in better overall maintenance of the properties along Princes Street.

Over the years, many of the buildings have had vacant upper floors while the focus was on maximising retail floor space on the lower levels. A lack of stairwells on upper floors was also problematic when it came to fire regulations, as there weren’t enough escape routes. Sadly, these neglected upper floors have often accelerated the risk of decay in many properties along Princes Street.

However, all of the recent proposals we have reviewed aim to repair and reinstate these upper floors with improved access. Using the upper floors means that new stairs or lifts will be installed to safely get people in and out. For us, this is a positive outcome, as people will be able to enjoy and inhabit these historic buildings for years to come and will continue to enjoy the fantastic views of Edinburgh Castle.

One of the most high-profile renovation proposals on Princes Street is for the former Jenners building. In January 2023 a fatal fire broke out in the former department store. Renovations are set to commence again following a police investigation into the fire. Our experts have been on hand to offer advice and support around fire safety in historic buildings. Our thoughts continue to be with the friends, family and colleagues of Barry Martin, the firefighter who died in the line of duty.

From houses to department store to tourist attraction

Looking at the West End corner (144-147 Princes Street) in particular, the site’s history is typical of Princes Street.

This site was originally residential houses in the Georgian style. These were extensively altered and converted into the Osbourne Hotel around 1873, thereafter used by the Scottish Liberal Club.

In the Victorian period, Robert Maule bought the buildings. He converted them to the Robert Maule & Co. department store.

In 1935, the store was bought over by Binns, a Yorkshire-based department store, which demolished and re-built the façades of the front building. This resulted in the Art Deco style which we recognise today.

House of Fraser, another upmarket department store, bought out Binns in 1953. However, the store continued trading under the Binns name for some time. Interestingly, at some point the building around the corner (3 Hope Street) was incorporated into the site. A purpose-built Royal Bank of Scotland from 1930, it is of similar architectural styling. However, you can see that the height of the floors do not quite match up to the connect building on the corner.

A 21st century experience

In September 2021, the building was given a new lease of life by the Johnny Walker Experience, becoming a new visitor attraction for the city. This saw more changes to the property, including a new rooftop bar. Lately, there has been a desire to situate bars and restaurants on Edinburgh’s rooftops. These applications are assessed on a case by case basis by the local planning authority. The rooftop extension by the Johnnie Walker Experience is a successful example. It doesn’t impact on the appearance of the 1935 listed building, which originally had its roof hidden behind the frontage when seen from below. It’s certainly the perfect spot to take in wonderful views across the Waverley valley to the Castle!

The renovations carried out by Johnnie Walker, also included sympathetic restoration to the exterior. One prominent improvement were the repairs to the 1960s clock which is a much-loved feature for locals and tourists.

What next?

Hopefully this romp through the fates and fortunes of Princes Street has highlighted how the street has always changed over time. With current pressure of online shopping and post-pandemic lifestyles, Edinburgh’s main commercial street is moving into a new phase of development.

The City of Edinburgh planning department is likely to see more applications coming in for reuse of the buildings on Princes Street. Remember that the public is always welcome to get involved in this process.

If you’re passionate about Edinburgh’s built heritage, it’s always worth keeping an eye out for any future proposals. Due to the size of these buildings, many developers are required to consult on their redevelopment plans.

You can also:

- sign up to receive the Edinburgh planning weekly lists.

- find out how to get involved in major development proposals.

If you are interested in the regulatory standards we apply in managing change to the historic environment, read our series of non-statutory guidance notes on how to apply the Historic Environment Policy for Scotland.