Edinburgh’s extension over the centuries has seen many villages and historic houses enveloped within the growing city. Some mansions, like Niddrie Marischal, were lost within the rapidly extending city boundaries. However, others have survived and flourished, finding new uses, albeit in changed contexts.

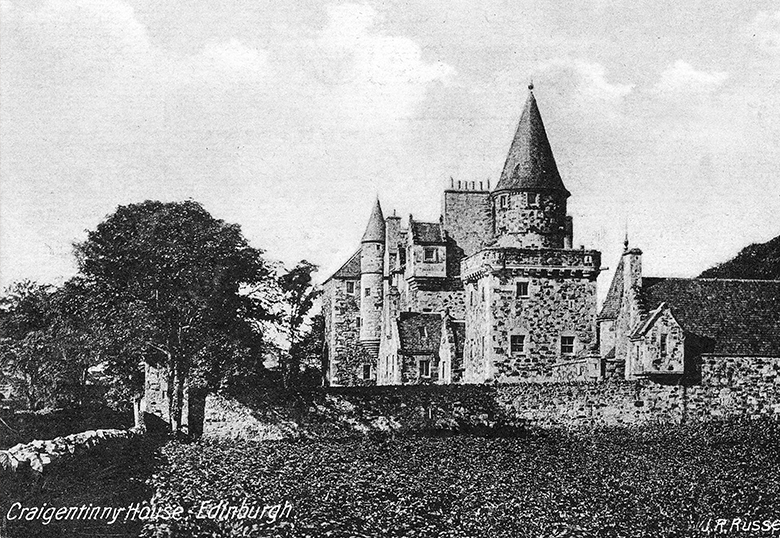

One of these is Craigentinny House. This early 17th-century house, with a famously eccentric former owner, was converted in 1938 to provide the first community centre in a Scottish council estate.

In my work with Historic Environment Scotland’s Planning, Consents and Advice team, I’m used to looking at proposals for the reuse of historic buildings. One innovative reuse project from the 1930s recently caught my eye. The repurposing of Craigentinny House saved a historic Edinburgh mansion from loss, became a longstanding asset to the community and could provide inspiration for today’s developers.

The Millers

In the early 1600s, the ancestral estate of the Logans of Restalrig was sold and split into three parts. One of these thirds became Craigentinny, which lies to the north-east of the ancient village of Restalrig.

Its new owner James Nisbet built the fortified house after 1604. After passing through various Nisbet lairds it was bought in 1764 by Willliam Miller (1722-1799). He was a wealthy Edinburgh seedsman and Quaker. He later moved to London where his son William Henry Miller (1789-1848) was born and raised.

Craigentinny House, pictured around 1900. Head to Canmore to zoom in. © Courtesy of HES (Ian G. Lindsay Collection).

Miller Jr served as a Staffordshire Tory MP but most of his free-time and income went on collecting books. He gained the nickname ‘Measure Miller’ from his habit of carrying a ruler to auctions to check a book’s dimensions.

Miller spent little time at Craigentinny, which was often occupied by caretakers. This is perhaps understandable when one considers the house’s significant shortcomings. It overlooked the infamous 250 acre Craigentinny Meadows. This profitable area of grassland was fed and irrigated by Edinburgh’s original ‘Foul Burn’. This burn carried the Old Town’s raw sewage into the sea from at least the mid-eighteenth century. The irrigated grass was fed to over 3000 cows in the vicinity, an arrangement which survived until the 1920s when the Council built a new piped sewer. Happily, today this discharges in Seafield Treatment works rather than the sea.

Carrying out his wishes

William Henry Miller, a bachelor, died in 1848. He left his estate to two unmarried sisters, seemingly unrelated to him, largely, it appears, to spite his nearest heirs.

However, his heroic book-buying had left substantial debts. A direct relation of Miller’s, Samuel Christy, was independently wealthy and provided financial assistance to the Marsh sisters. Christy dealt with the debts and provided the money for the Marsh sisters to improve the estate. For example, building new additions to the castle and a walled garden. Perhaps this wasn’t completely altruistic. Christy was next in line to inherit from the spinster sisters in Miller’s will. Once the sisters died Christy inherited the estate. At that point, he changed his name from Christy to Christie-Miller – adding Miller was essential to inherit the estate and Arms.

Christy repaired, extended and Baronialised the house in a convincingly historic manner, which was popular at the time. He employed the architect David Rhind, who also designed Miller’s elaborate mausoleum (now category A listed). The tomb was known locally as the ‘Marbles’ from its decorative Rome-carved panels in Carrarra marble.

This photo showing Miller’s tomb was taken in around 1965. Take a closer look on Canmore.

Vampires in Craigentinny?

Miller had left strict conditions on his burial which included a lead-lined coffin within a stone-lined vault (estimates of its depth range from 17.5ft to 50ft). After his delayed internment estate workers held nightly vigils around the graveside. The unusual burial, in open fields far from consecrated ground, led to rumours. Within six months of his death, newspapers were suggesting that Miller, who was beardless with a thin figure and weak voice, had been a woman, and thus Britain’s first female MP. Later in the 19th century it was suggested Miller was in fact a fairy changeling, and this has culminated in more recent suggestions that Miller was a vampire, and his elaborate precautions were to prevent him rising from the dead!

Whilst I am loath to ruin a good story, it’s more likely that Miller had a fear of graverobbers. Edinburgh was a leading European centre of anatomical study in the early 1800s and the need for bodies to study drove an illegal trade in dead bodies, eventually culminating in the famous murders carried out by Burke and Hare.

Additionally, the depth of the vault was necessary to withstand the weight of the huge mausoleum he had envisaged, later scaled down due to costs.

It is likely that the gossip about him was spread by his disgruntled Miller heirs who wanted to discredit his legitimacy – during a long legal challenge to his will – but many Edinburgh folk will have their own theory.

Lady Nis-bit?

Amazingly, this isn’t the first time vampires have been associated with Craigentinny. A newspaper story from 1907, with more than a nod to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), told how a previous owner of Craigentinny in the 1720s, Lady Nisbet, had become a vampire and was feeding on her husband’s blood, before biting the family’s cook. She was chained in her room, and a visiting Bohemian doctor was consulted about her behaviour. The drama culminated in Lady Nisbet escaping, stabbing the doctor and turning the knife on herself before being struck by lightning and killed. The fanciful tale alleges that Lady Nisbet was buried in an ‘obscure corner’ of the estate with a stake through her heart.

New beginnings

The Christie-Millers retained the house and estate into the early 20th century, but the city was fast encroaching. Part was leased to a golf course, but all changed in 1931. A compulsory purchase of 62 acres was carried out by the City Council for desperately needed council housing. The remainder was then sold to private developers like James Miller (no relation) to build bungalows.

Taken in 2014, this aerial image shows Craigentinny House surrounded by suburban buildings which have sprung up in the past 85 years.

Craigentinny House (or Castle, if you prefer) survived, marooned in a sea of new housing. It was unused and under threat of demolition.

Happily, in March 1937, Edinburgh Council bought the house for £1000. The following year they converted it, at a cost of £3000, into a social or community centre. This is believed to be the first council facility within a Scottish housing estate. Described as ‘a sunshine centre from which rays of happiness, health and good citizenship will permeate the extensive area it will serve’, it catered for the estate’s new population of 12,000 residents.

Many instructive and educational classes, dances and club meetings were held in the building. It also housed a library, billiards room and gymnasium converted from the stables.

All was well until 6 August 1942 when a Luftwaffe bomb fell, destroying the entire eastern half of the house, and tragically killing the resident caretaker, 68-year-old Robert Wright. The convincingly Baronial mid-19th century additions by Rhind were lost but the original rubble 17th-century house remained. Afterwards, it was repaired and extended for continued use. It has been category B listed since 1970.

Craigentinny today

Today, this 400-year-old turreted remnant of a rural Edinburgh estate still fulfils a valuable function as a council community centre serving the population of Craigentinny, Restalrig and Lochend. As well as continuing the many classes and events within the building, there is now a warm space where people can drop in throughout the day to save on heating bills.

If you visit the building today you can still see clues to its long history, inside and out.

Here to help

Craigentinny is a good example of a building having a new lease of life through beneficial reuse. The planning, advice and consents (PCAS) team at HES support many new and continued uses for listed buildings. We offer specialist advice on how to retain their character and special interest.

As many will know, HES’s HQ at Longmore House is itself a converted hospital, but finding new uses for the many buildings on our Buildings at Risk Register, and also the many churches that are now becoming obsolete, will be a challenge.

Find out about the work of our Planning, Consents and Advice team.

If you’ve enjoyed this blog, you might also enjoy The changing face of Princes Street, looking at the architectural evolution of one of Scotland’s most iconic thoroughfares.

Banner image credit: photo in the background shows a postcard © Courtesy of HES (Ian G. Lindsay Collection).