If you were in Glasgow Cathedral around this time 385 years ago, it would not have been the peaceful haven in the heart of the city that it is today. Noise abounded and rowdy crowds packed the galleries as the General Assembly of 1638 took place below.

It’s without a doubt one of the most significant events in Glasgow’s history, although the story traditionally begins in another cathedral…

Duck, Dean!

On 27 July 1637, Jenny Geddes allegedly got up and hurled her stool at the Dean of St Giles in Edinburgh.

Tradition has it that the furious market-trader was objecting to the first public use of the Scottish Episcopal Book of Common Prayer in Scotland, or, more simply, the Scottish Prayer Book.

Inside St Giles Cathedral

In the 1630s, Charles I, known for his political mismanagement, had made it clear he wanted to bring the Church of Scotland more in line with the Church of England.

His father, James VI & I, had also sought to do this and had done so with some success which had resulted in a hybrid system of church governance between Presbyterianism and Episcopacy.

In the Presbyterian model there is no hierarchy of clergy. Jesus Christ is considered the head of a church governed by a series of courts. The highest of these is the General Assembly. The meetings are overseen by a temporary moderator, and no commissioner has greater voting rights than any other. Episcopal (or Anglican) churches, meanwhile, follow a hierarchical model, governed by bishops.

James’ mix of the two models was accepted, albeit with some resentment. Charles, however, wanted to go further.

A 19th century painting of the signing of the National Covenant by William Hole (© Edinburgh City Art Centre, licensed via Scran)

Rising resentment

At this time Scotland was ruled through a Privy Council. Charles I had little interest in his northern kingdom, or the subtleties required to govern it. He passed several measures that were highly unpopular, creating suspsicion and resentment in all elements of Scottish society.

These included increasing the number of bishops in the Privy Council, which reached new heights when he awarded the highest civic office, the Chancellorship, to the Bishop of St Andrews. This did not go down at all well with the Presbyterian clergy who believed church and state should be kept separate. Many Scottish nobles, who had felt increasingly disenfranchised after the royal court had moved to London in 1603, were also resentful at the growing influence of the bishops.

Not in my book

While the Presbyterian party were in the minority, its leaders were very astute. They were particularly good at exploiting the situation created by Charles, enflamming general dissatisfaction and suspicion.

This came to a head when Charles pushed forward with bringing Scottish liturgy (the way that church services are carried out) in line with England. The introduction of the Scottish Prayer Book, which famously drew the ire of Jenny Geddes, proved the catalyst for significant change.

Crucially, the new prayer book had not been approved by the General Assembly or the Scottish Parliament. Moreover, it had been rumoured to be Roman Catholic in nature. This could exploited by the committed Presbyterian clergy to fuel riots like that sparked by Geddes.

Understandably, after the riots, the clergy and bishops were reluctant to continue trying to use the book. This led the dissenting elements in society to draw up a document that became known as the National Covenant.

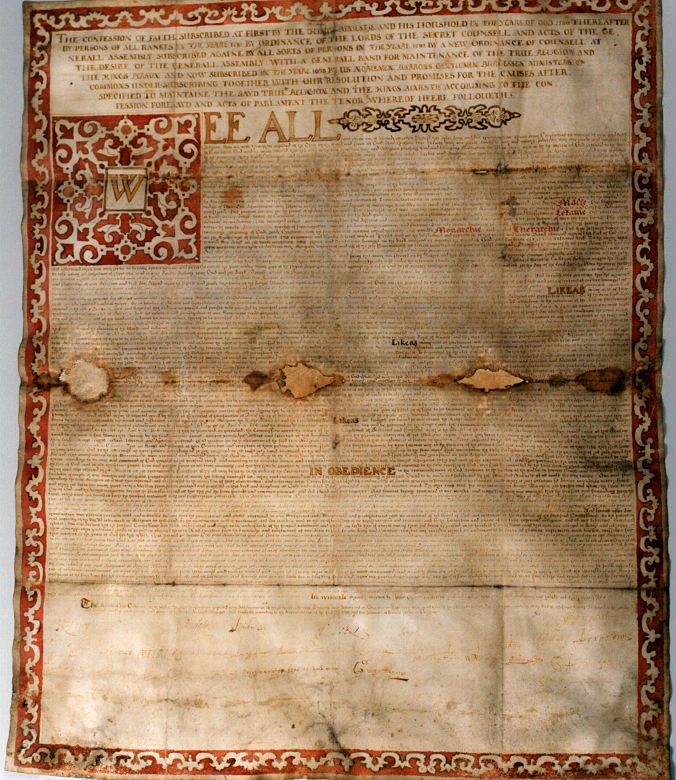

A copy of the National Covenant, calling for all Scots to oppose the religious policies of Charles I (© National Museums Scotland, licensed via Scran)

What was the National Covenant?

The National Covenant was deliberately vague to appeal to as many of the disgruntled factions as possible. Although the bishops and prayer book are not explicitly mentioned, there could have been no misunderstanding that they were being referred to.

It rejected any “innovations” placed on the Scottish church’s reformed worship but emphasises the signatories’ loyalty to the King. Thus, it stopped short of being treasonous.

The Covenant was signed on 28 February 1638 in Greyfriars Kirk in Edinburgh. Copies were sent across Scotland, where it was received enthusiastically, except in the north east. The document would become a rallying point in the coming decades for the party that would become known as the Covenanters.

The General Assembly of 1638

In the midst of all this, it was announced that, for the first time in nearly 20 years, a General Assembly would be held in Glasgow in November.

Glasgow, having a relatively small population at the time, was probably chosen over Edinburgh to make large scale riots less likely. Still, the Assembly would prove lively and needed to be very carefully managed.

The Presbyterian faction managed to ensure those who had signed the National Covenant were elected as elders. This meant they could attend the Assembly with voting rights. It was also made clear that anyone who wasn’t elected but had either signed or was sympathetic to the cause was allowed to attend. The bishops did not attend.

The Moderator of the Assembly was elected by members with voting rights. On this occasion, it was Alexander Henderson, one of the Covenanters, most formidable leaders. The minister of Leuchars in Fife, he had drafted the Covenant together with Edinburgh lawyer Archibald Johnston.

Crowds and condemnations

On 21 November, a rather rowdy crowd descended on Glasgow Cathedral and packed into the nave. Many people, including women, watched from the triforium (gallery) above. One of the commissioners complained of the noise in the Cathedral and that it was inappropriate for a church.

On 28 November, the King’s Commissioner, the Marquis of Hamilton, gave up trying to control the Assembly and left. The commissioners then passed a series of measures over the next fortnight:

- All measures taken to impose elements of Anglican worship, including the Scottish Prayer Book were condemned and annulled

- The office of bishop was abolished

- All of Scotland’s bishops were excommunicated

- Clergy were forbidden from holding civic office

- It was decided that the General Assembly would meet annually

The nave at Glasgow Cathedral

A seismic summit

The General Assembly concluded on 6 December, but the effects of that fortnight in Glasgow Cathedral were long-lasting and far-reaching.

The sweeping away of all the reforms to impose Anglican elements onto the Church of Scotland introduced by James VI & I and Charles I was revolutionary for the church. Effectively, it amounted to treason.

Only the naivest of any of attendants wouldn’t have known that the measures passed would inevitably lead to armed conflict. Perhaps they did not foresee that it would usher in five decades of civil strife, that would include civil war. Religious persecution, intolerance and intimidation would be endemic with suspicions being fanned by both Government and Covenanting forces. This would see senseless killing all over Scotland, but particularly in the southwest.

Episcopacy would end up being restored for a time until after the Glorious Revolution. An Act of Parliament in 1690 would see the Church of Scotland being established as Presbyterian. It remains so to this day.

Visit us at Glasgow Cathedral

Glasgow Cathedral is one of the finest buildings of the 1200s to survive in mainland Scotland. It’s open daily for visitors to explore. Highlights include the awe-inspiring nave to the crypt built in the mid-1200s to house the tomb of St Mungo.

Want more cathedral stories? Check out how dendrochronology was used to uncover some of the secrets of the St Giles Cathedral tower.