I used to be in pantomime but it’s all ‘behind me’ now.

Any reader fortunate enough to have grown up in Renfrewshire in the early 1990s may have witnessed my star turn in Hansel & Gretel at Paisley Arts Centre.

The author in pantomime mode in nineties Paisley.

It was a role I took with some reluctance, to be honest (but an actor out of work in panto season is doomed, just as few theatres can afford to go ‘dark’ during the season of high bum-to-seat ratio). In the event, it proved to be one of the most enjoyable jobs of my brief acting life.

I appeared as the witch’s henchman, half of a double-act with my old chum Kevan Mackenzie (who you may have seen in the BBC crime drama Shetland) and we had a ball, performing two to three shows a day to packed, enthusiastic houses. Happy days.

A natter with Baxter

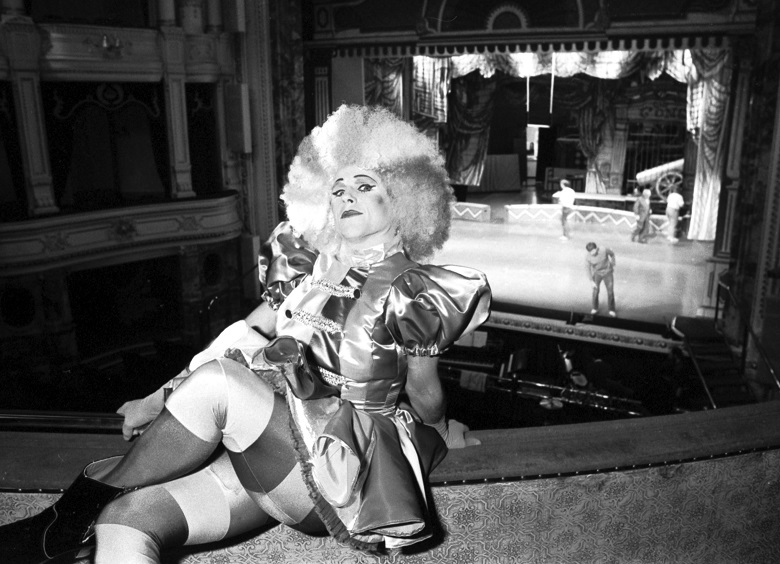

Stanley Baxter playing Widow Twankey in Aladdin at the King’s Theatre in 1985. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN))

Even further back in the mists of my chequered career, I was an eager young journalist interviewing Stanley Baxter, one of the great megastars of Scottish panto. We met, if I recall correctly, in the green room of the King’s Theatre, Edinburgh.

Baxter (larger than life in three-piece tweed suit and highly polished shoes) regaled me with tales of elaborate costumes, quick changes and buses affy which ye cannae shove yer granny. Happy days indeed.

Changes at King’s

A drawing of the exterior of King’s Theatre dating from 1945. Note the pantomime signs! (© The King’s Theatre Trust. Courtesy of HES. Zoom in on Trove.scot)

Baxter retired from the stage in 1990, while the King’s Theatre is now undergoing a major refurbishment.

The raked stage is being levelled, allowing dancers to pirouette without fear of spinning off into the front row of the stalls, the concrete fire escapes have been replaced with modern staircases and accessible lifts, and the bars, toilets and dressing rooms are all being made spick, span and regulation-compliant.

But the show must go on, and the King’s has never been the only option for your pantomime watching needs…

A plethora of pantos

Elaine C Smith engaged in typical pantomime action in 1985. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN)).

Elaine C. Smith is a stalwart at the King’s in Glasgow (in 2025 they’re giving The Little Mermaid the panto treatment).

The Palace in Kilmarnock is undergoing refurbishment so Sleeping Beauty will be at the Galleon Centre this year. His Majesty’s in Aberdeen are doing Cinderella, The Byre Theatre in St Andrews have Aladdin and there’ll be at least a dozen more greasepaint-and-groaners-heavy entertainments throughout the enchanted land of Scotia. It’s the perfect place for it!

At home in Scotland

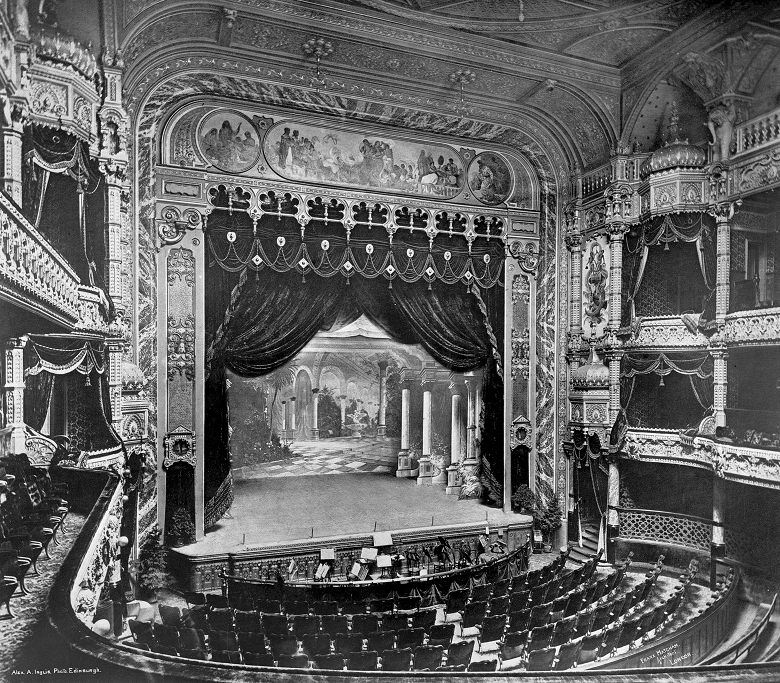

The interior of the Empire Theatre – now the Festival Theatre – on Nicolson Street, Edinburgh, in around 1910. (Courtesy of HES (Scottish Colorfoto Collection))

The pantomime genre seems to have grown out of ‘dumb shows’ that were popular in Britain in the mid-1700s. They in turn drew on the Italian commedia dell’arte, with its farcical plots and stock characters, such as the mischievous harlequin and the miserly pantalone.

But the performance style we know today has its roots in the variety shows that were the backbone of the light entertainment industry before the advent of television.

The Edinburgh Grand Theatre’s Pantomime Annual for 1904/1905. Like a modern day programme, it gave the audience some behind the scenes insight into the year’s panto. Miss May Marton played Cinderella, with Miss Milie Engler as the Prince. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN))

Pantomime is a characteristically British form of performance, but Scotland is often said to be its natural habitat. As early as 1808, the Edinburgh writer Walter Scott was deploring ‘the garbage of melo-drama and pantomime’.

By the 1870s, the Edinburgh actor/playwright William Lowe was drawing on Scottish folklore and writing dialogue in Scots for the comic characters. And around the same time, writers were sprinkling the scripts with local and topical references we now expect.

Nellie Wallace and Stanley Lupino in Aladdin at Glasgow’s Theatre Royal in 1924. The signpost for Paisley is typical of local references which are sprinkled into pantomime scripts and settings. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN))

The name of the dame

Meanwhile, performers from the variety tradition were introducing their own brand of boisterous and bawdy humour. Increasingly, panto became a vehicle for stars from that background, who came to be seen as essential to attract the crowds.

The dame – by long tradition a male performer in exaggerated drag – emerged in the late 1800s as the linchpin of the panto. They addressed the audience directly, performing set pieces, frequently changing costume and sometimes inviting children from the audience onto the stage.

Ballet dancer Wayne Sleep in drag as Goldilocks’ mother in the Edinburgh King’s Theatre’s Christmas pantomime, December 1988. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN))

“Pantomime daft”

By the 1930s, pantomimes were running in Scotland for at least 20 weeks of the year, providing performers and theatres with much of their annual income. In 1956, the author E.G. Ashton noted that:

Scotland is, quite simply, pantomime daft … Audiences travel from fishing hamlets, mining villages, country towns, and even from one city to another in order to see a pantomime.”

There can be little doubt that many of Scotland’s surviving Victorian and Edwardian theatres owe their longevity to the popularity of panto. And over the decades it has proved an agile shape-shifter, adapting time-honoured tradition to changing sensibilities.

The interior of King’s Theatre, Glasgow around 1930. (Courtesy of HES (Scottish Colorfoto Collection)

Enduring silliness

In recent decades, some theatres have placed a greater emphasis on storytelling, relegating the ribald wordplay, gaudy costumes and silly set-pieces in favour of meaningful plot and characters.

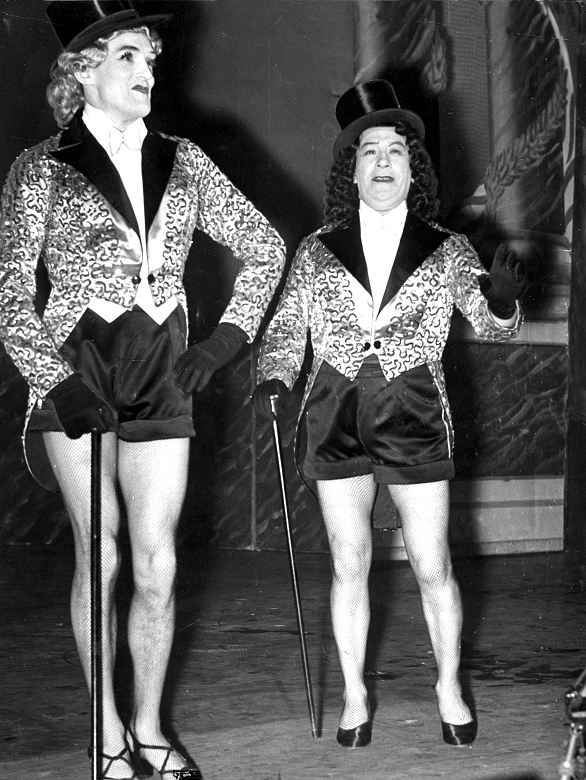

But others continue to embrace the full gaudy glamour of ‘trad’ panto. It’s a mark of the genre’s resilience that even today, the drag dame is still a thriving species.

Jimmy Logan and Harry Gordon on stage in a 1956 pantomime. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN))

My children are teenagers now and – alas – far too cool for Cinders. As I sat down to reflect on the ghosts of pantos past I did wonder if the final curtain might be beginning to fall on this much-loved institution.

The answer is clear to me now. What do you think, boys and girls?

Audience: Oh no it isn’t!

See more in the archives

Scottish entertainer Una McLean as Principal Boy in the Babes in the Wood pantomime at the Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh in December 1970. (© The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed via Scran)

The amazing photos used in this blog are from the HES Archives which include the records of SCRAN.

You can look through some of these images at trove.scot, the newly launched online home for our archives and protected places. We’re still working on migrating content from Scran so if you can’t spot what you’re looking for, do keep checking back!

Alternatively, take a look at our other archive blogs – the Archives archives, if you will. They cover everything from to a visual tour through Leith’s past, to a history of cycling and even Doctor Who!

This post originally appeared on the blog in December 2023 – but has been updated for 2025.