Heads up: some quotes used in this post reflect attitudes and understanding of the time that readers might find offensive.

Today, Scotland is home to a significant number of Chinese people, including a vibrant student population. Yet before the 1950s, few Chinese settled in Britain, and even visitors from China and Hong Kong were rare. Among those few who came to Scotland in earlier times, five were notable: William Macao, Huang Kuan, Boshan Wei Yuk, Wang Tao and Chiang Yee.

From the first “Chinese Scotsman” to the first Chinese student and Scotland’s first Chinese travel writer – here are five fascinating figures from Scotland’s Chinese history.

William Macao – Scotland’s first Chinese Scotsman

When William Macao arrived in Scotland around 1775, he was only the fifth Chinese person known to visit Britain. So unusual was the sight of a Chinese man in Britain that the previous four all met the King and had their portraits painted. Later, Chinese visitors were even documented in newspapers. Although Macao became the first known Chinese to settle in Britain, his life remained almost completely unrecorded. Until I chanced upon a mention of him and unearthed his remarkable life.

That Macao neither met royalty nor had his image recorded is unsurprising. Macao arrived in Scotland aged 22, with a man named Dr David Urquhart. He lived and worked on the Black Isle, far from society.

In 1778 a neighbour of Urquhart’s, Thomas Lockhart, a Commissioner of Excise in Scotland, employed Macao as his footman at his house at 23 George Square, Edinburgh.

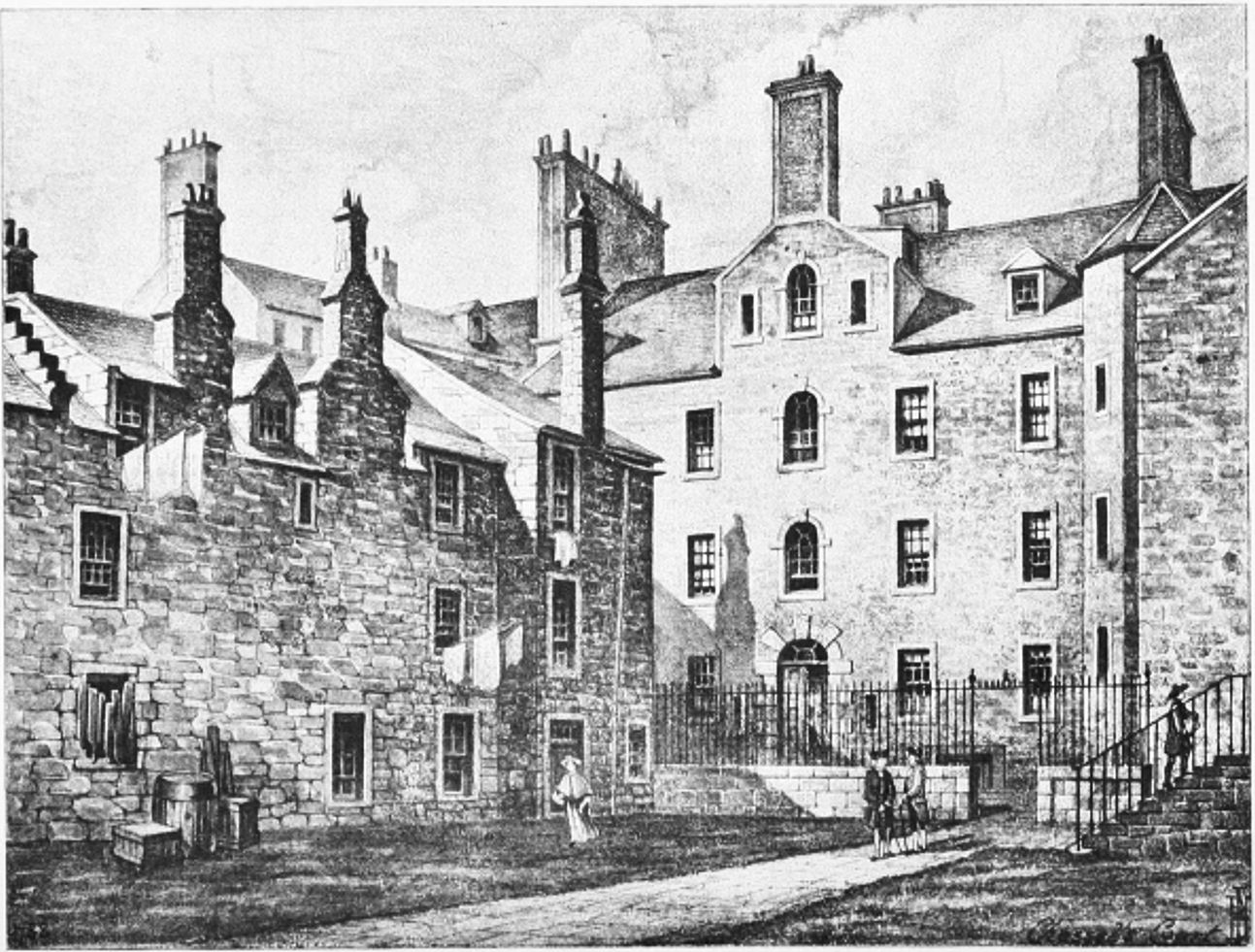

Lockhart’s house at 23 George Square in Edinburgh

Unfortunately, Lockhart died in 1780. As his widow did not need a footman she arranged for the young Macao to be given a job as a servant to the clerks in the Board of Excise. First at Chessels Court and later at Dundas House in St Andrew Square.

Remarkably, when Macao retired from the Board of Excise in 1823, he had risen to be the Board’s Accountant of the Superannuation Fund. That’s an achievement for anyone, let alone the only Chinese man in Britain.

Chessels Court, Edinburgh, c.1780

Britain’s first “Chinese Scotsman”

Macao wasn’t just the first recorded Chinese person to settle here, he was also the to wed a British woman in Britain. On 21 December 1793, he married Helen Ross of Inverchasley, and they had three children.

Church records indicate that Macao and his children were the first people of Chinese descent, admitted into the Church of Scotland. Macao even became a kirk elder at Rose Street church.

This is all notable enough and yet his story has a further extraordinary element. In 1818, a foreign merchant in London came across a clause in the Scottish Parliament Act of 1695 that stated that all foreigners who purchased bank shares would, ‘thereby become a naturalized Scotsman … and as such, a naturalized British subject’.

The merchant, and over 140 others, including Macao, bought the requisite shares on the presumption that this endowed British citizenship. The government were outraged at this potential undermining of their power to bestow citizenship. Eventually, it was agreed that a court case should be brought by one of those who had bought shares to determine whether the clause still had force.

The Bank of Scotland selected Macao and in January 1819 Lord Alloway ruled that the clause stood. Macao was, therefore, a naturalised Scotsman. However, Alloway left undecided whether this also meant Macao was a naturalised British subject.

When the Government appealed eighteen months later, Alloway’s ruling was overturned. But this still means that for a time William Macao had the unique status of being the only individual since the Act of Union to have been legally decreed a Scottish citizen. Since 1707 all other citizens of Scotland have been legally designated British. Britain’s first Chinese Scottish gentleman is buried alongside his wife in St Cuthbert’s graveyard.

Dr Huang Kuan – Britain’s first Chinese graduate

In 1850, Huang Kuan (also known as Wong Fun) came to Edinburgh to study at Edinburgh University Medical School. He became the first Chinese student to graduate from a British University. Hundreds of newspapers reported the news across the country.

Huang excelled in his studies, particularly under Professor John Balfour, in whose Botany Class he won a number of prizes. On becoming a doctor, Huang Kuan moved to Canton where he worked with The Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society. There, he performed different types of surgery and he is credited with educating a new generation of Chinese doctors.

Statue of Dr Kuan Huang in the Edinburgh Confucius Institute’s garden, University of Edinburgh

Dollar’s Chinese visitors

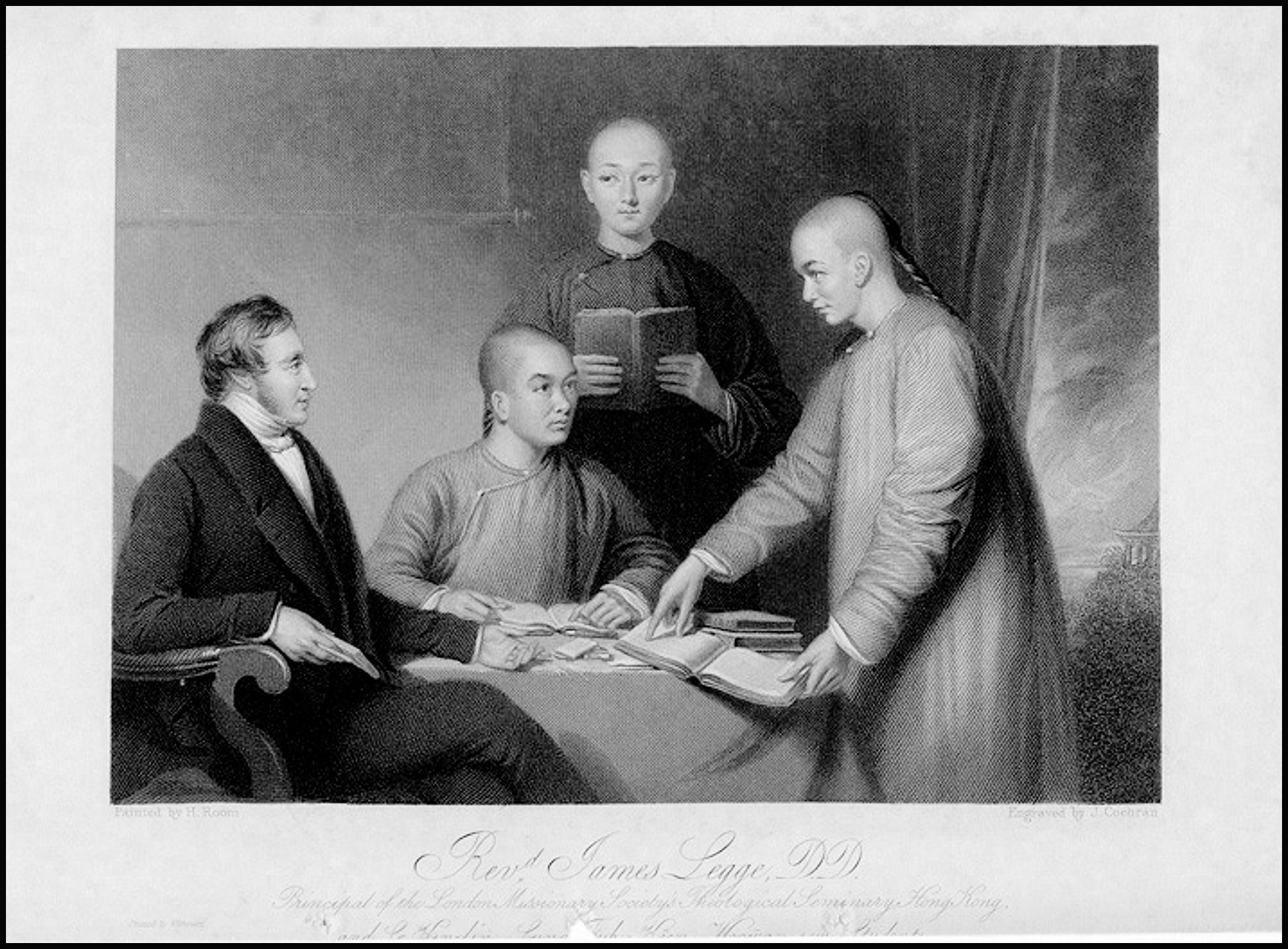

James Legge was a Scottish missionary who visited China on many occasions. He was living in Dollar in the 1860s and in 1868 arranged places at Dollar Academy for four boys from Hong Kong, including Boshan Wei Yuk, whose father worked for the Chartered Mercantile Bank of India.

Dollar Academy

Throughout their time at the Academy, all four wore traditional Chinese dress and ‘were never annoyed by rude and idle curiosity, as was the case when they ventured to pay a visit to some of our large towns.’

As well as the traditional subjects the boys learnt the Highland Fling. Like his father, Boshan Wei Yuk joined the Chartered Mercantile Bank of India, London and China, and became a prominent Hong Kong figure, including a member of the Legislative Council. He was knighted in 1919 and named his Hong Kong mansion Braeside in memory of his years in Dollar.

James Legge and three students that attended Dollar Academy

Wang Tao – Scotland’s first Chinese travel writer

In 1867, Legge brought Wang Tao to stay with him in Dollar to assist him in translating a number of Chinese classic books. Earlier, Wang had worked for the London Missionary Society Press in Shanghai assisting Legge with his translation of the New Testament and other books into Chinese. One of the Chinese texts the two men translated while in Dollar was the I Ching.

James Legge and family and Wang Toa at Dollar, 1870

Wang wore his native costume and on one occasion when visiting Aberdeen, a group of children allegedly pointed at him, shouting, “It’s a Chinese lady!”. Wang Tao travelled extensively within Britain and Europe, writing poems and a journal related to his travels. On his return to Hong Kong in 1870 Wang became an independent journalist, founding and editing one of the first modern newspapers in China.

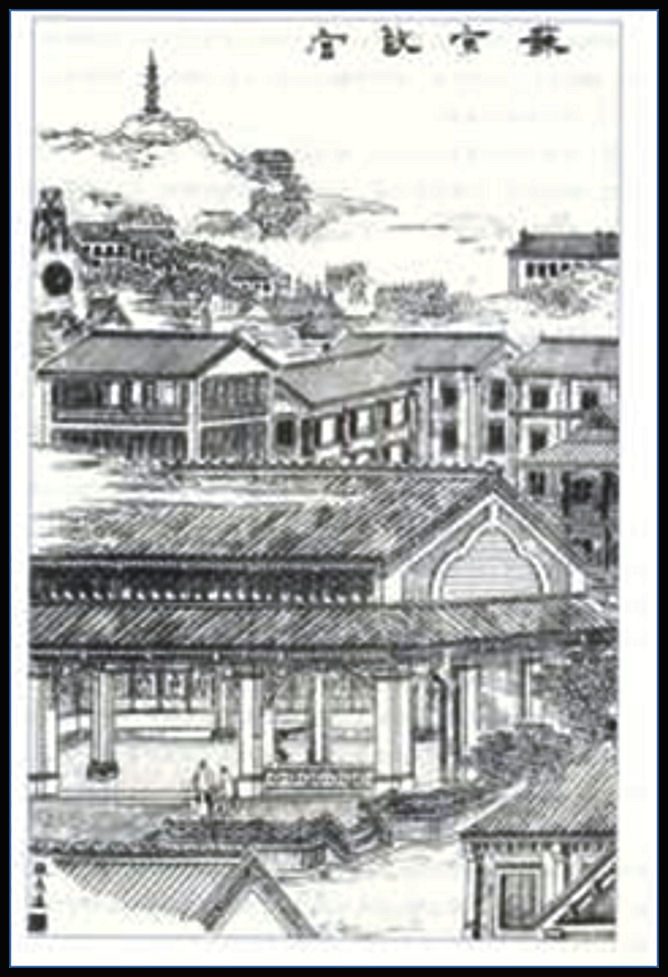

In 1890 his book, Jottings from Carefree Travel was published in China. It was the first travel book about Europe by a Chinese scholar. For the publication, illustrations were commissioned from local Chinese artists. But the artists had no knowledge of the actual view. They used their imaginations and thus the illustration of Holyrood, titled The Old Palace of Edinburgh, shows a Chinese palace. And Edinburgh’s Nelson Monument on Calton Hill became a pagoda.

Chinese illustration of Calton Hill, Edinburgh from Jottings from Carefree Travel

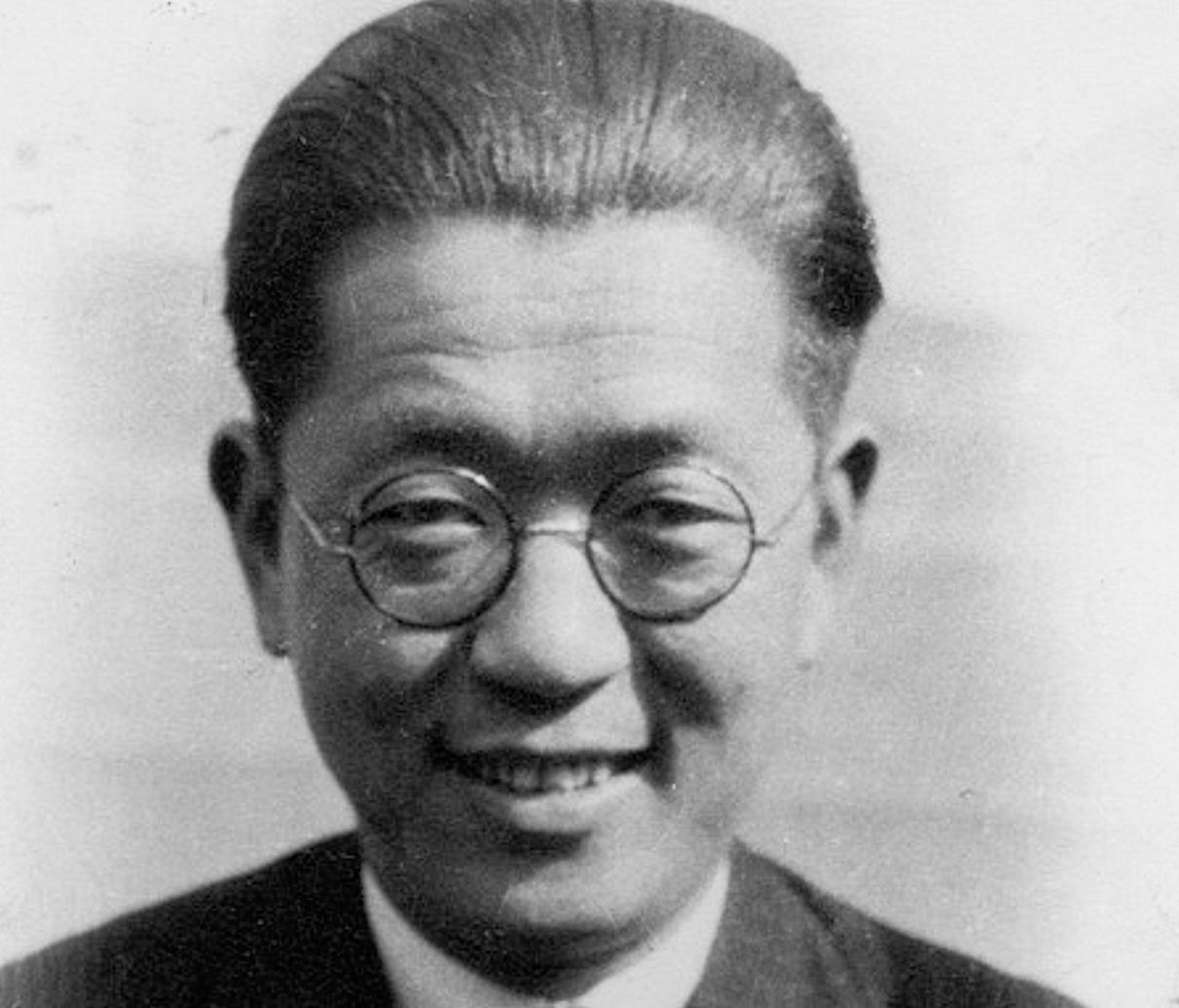

Chiang Yee – The Silent Traveller

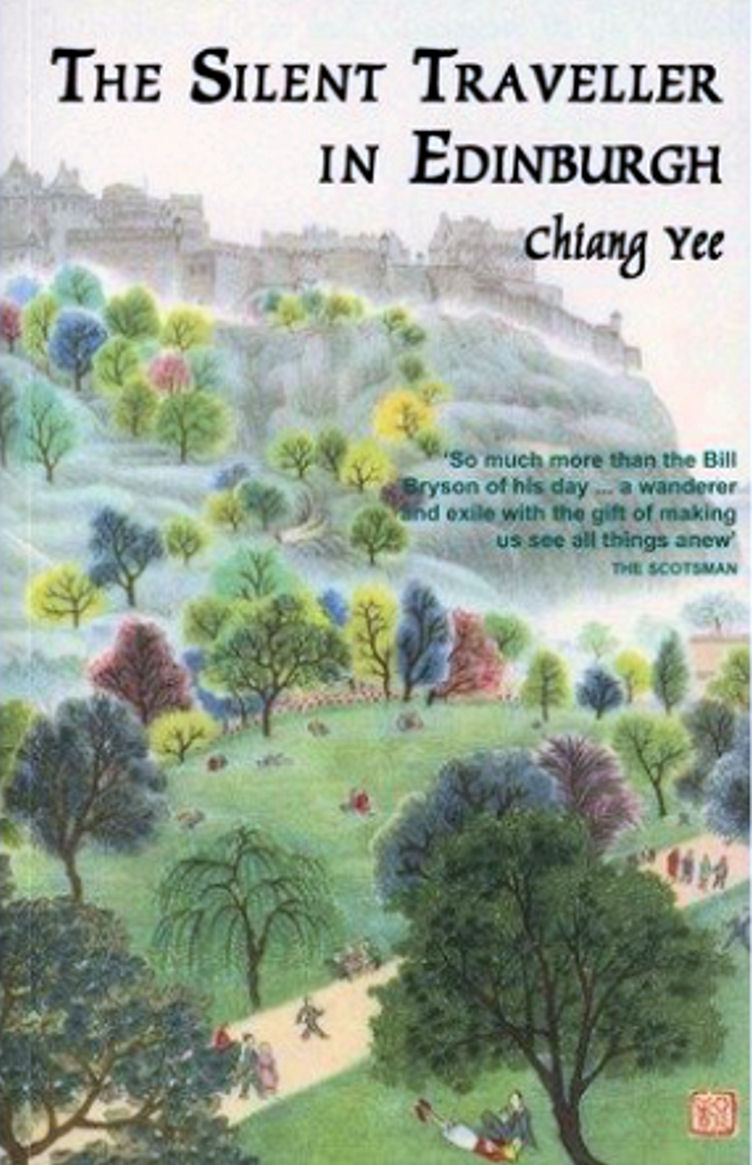

The fourth visitor, Chiang Yee, only visited Scotland for a short time. But his visit resulted in a delightful book, The Silent Traveller in Edinburgh. It paints an engaging portrait of the city in the 1940s. This was one of a series of ‘Silent Traveller’ books that he wrote.

Chiang was born into a wealthy, middle-class family in Jiangxi province, in south-west China and by 1930 an influential magistrate. But in 1933 Chiang decided to abandon his Chinese life and family. With no job in prospect and speaking almost no English, he travelled to Britain. In London, Chiang started learning English. He began exhibiting paintings and illustrations that became highly regarded. In 1935 he published a book on Chinese painting, The Chinese Eye: An interpretation of Chinese Painting, that brought him further acclaim.

For his first ‘Silent Traveller’ book he chose the Lake District because of its historical associations with a number of Britain’s literary and artistic elite. The first publishers he submitted the book to rejected it. They considered the content to be ‘too Chinese’. But Country Life decided to publish it, and the book sold out in its first month. It was republished in nine subsequent editions. These illustrated travelogues provide a unique perspective on Britain through the eyes of a Chinese exile. This was at a time when books about the West by a Chinese author were exceptionally rare.

There have been many works about Edinburgh. But Chiang Yee offers a unique view of Scotland’s captital in The Silent Traveller in Edinburgh.

Chiang Yee and Edinburgh

The books’ charm comes from Chiang’s exploration of ostensibly trivial subjects. This includes the weather, teatime, children, books and the theatre.

One chapter in his Edinburgh book describes visiting the National Library of Scotland and looking at materials relating to Sir Walter Scott. He writes: ‘I have found that in nearly every place in which I have stayed there were copies of Scott’s works or some connection to his life, and that almost every beauty spot in Scotland is connected with Scott himself or his stories. I was told that Scott was to Scotland what Shakespeare is to England but from my little experience I must say that one could leave England without hearing of Shakespeare but never Scotland without hearing of Scott.’

About the author

Barclay Price worked in the arts and on his retirement happened to chance on a brief mention of William Macao. This led him to research Macao’s life and that of Chinese visitors and settlers over 300 years that became his first book, The Chinese in Britain. (Amberley Publishing). The paperback version is now available. He has since written a number of histories of areas of Edinburgh; the latest being A History of Stockbridge.

Barclay Price worked in the arts and on his retirement happened to chance on a brief mention of William Macao. This led him to research Macao’s life and that of Chinese visitors and settlers over 300 years that became his first book, The Chinese in Britain. (Amberley Publishing). The paperback version is now available. He has since written a number of histories of areas of Edinburgh; the latest being A History of Stockbridge.

Want to uncover more about Scotland’s “hidden” stories from history?

From the Gypsy Kings and Queens of Kirk Yetholm to Walter Sholto Douglas, the 19th-century Scottish writer and friend of Mary Shelley who was christened Mary Diana Dods at birth, there are many more fascinating stories on our blog.

Subscribe to our newsletter for stories fresh off the press straight into your inbox.