Kirk Yetholm is a picturesque village lying only a mile to the west of the Scottish-English border. Today it’s known as the end of the Pennine Way walk, but in 1898 it attracted national press coverage when an elderly man was crowned King of the Scottish Gypsies. His palace, the survivor of two former rival Royal residences in the village, can still be seen today.

So who was this King of the Gypsies, and why did this small Borders village have two palaces?

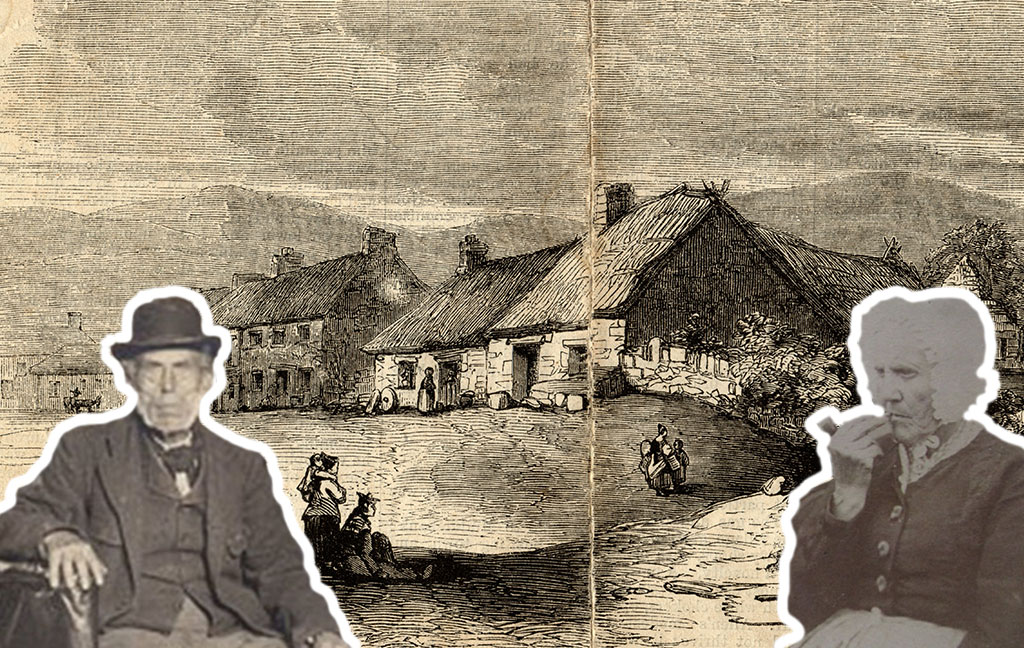

The village of Kirk Yetholm.

The Gypsy Royal Family

A modern authoritative history of the Scottish Gypsies is yet to be written. However, many legends and tales about their origins and exploits have been passed down through oral history.

The first official recognition of a Scottish Gypsy leader was in 1506. King James IV acknowledged Anthony Gawin as the “Earl of Little Egypt” in a letter which implored the King of Denmark to give Anthony and his company safe passage through Denmark.

“Little Egypt” was not a place, but a people. Egypt was the supposed ancestral homeland of the Romani people, and the derivation of the word ‘Gypsy’. Today, ‘Gypsy’ is sometimes seen as offensive. However, there are several Romani groups in Europe and Britain who have claimed this word and use it with pride. I’ve used the word Gypsy in this blog because this is how the community in Kirk Yetholm referred to themselves.

By 1540 leadership passed to the Faa family. James V granted John Faa and his son authority to police and punish their ‘subjects’. It was with this legislation that the tradition of the Gypsy Kings and Queens was affirmed.

From Power to Persecution

However, any tolerance from the established monarchy was short-lived. King James VI & I approved an ‘Act anent the Egyptians’ promising death for any of the Gypsy race found in Scotland after 1 August 1609.

In 1624 Captain John Faa and his kinsmen were hanged in Edinburgh with others banished abroad. Alongside official sanctions, feuds between rival Gypsy clans led to yet more bloodshed.

Continued persecution led many Border Gypsies to intermarry and adopt more recognisably Scottish surnames such as Young, Douglas, Baillie, Ruthven, Shaw, Tait and Gordon. Faa itself was often gentrified to Fall.

Living close to the border allowed for an easy escape into England.

Making a home in Kirk Yetholm

The early 18th century found several of the Gypsy clans settled in Kirk Yetholm. There are conflicting tales of how they received favourable leases by the landowner, Sir William Bennet of Grubett. One story tells of how they were granted the land after a Gypsy saved William’s life in the Siege of Namur in 1695, now in present-day Belgium.

It was on this land that cottages were built, including the Royal Palaces. The Palaces themselves were not larger or more grand than their neighbours. Instead, their status was bestowed upon them by their regal residents.

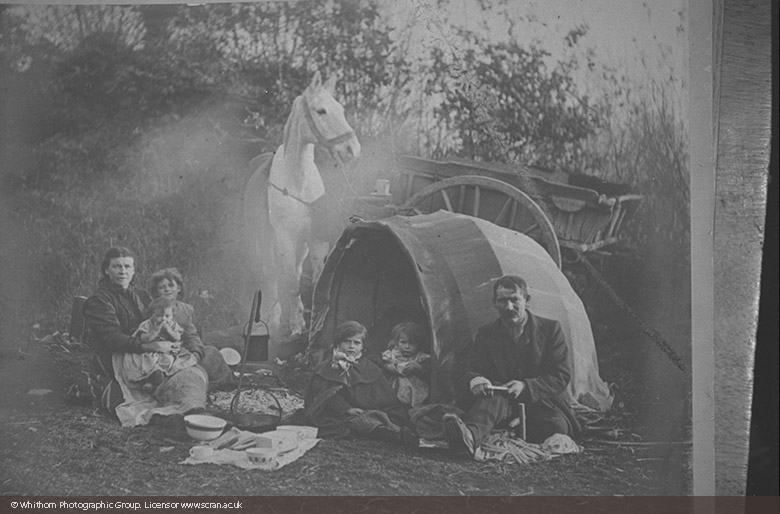

By the early 19th century there were over a hundred Gypsies resident at Kirk Yetholm in winter. Families would travel in groups throughout the summer months, mending and hawking hand-made goods around the countryside. They would live off the land in barns and under canvas. Many became ‘muggers’ or potters, selling earthenware, often purchased cheaply from manufacturers.

This photo, taken around 1906 shows a Gypsy family camped in Galloway. © Whithorn Photographic Group. Licensed via Scran.

The Kings and Queens

Let’s take a look at the dynasty of Gypsy Kings and Queens who made a base for themselves in Kirk Yetholm.

Patrick Faa

The first Gypsy King and Queen recorded at Kirk Yetholm were Patrick Faa and his wife Jean Gordon. Their reign spanned the 1730s and 40s. It is said that Sir Walter Scott based his character Meg Merrilies in ‘Guy Mannering’ on Jean.

According to a horrific account by George Eyre-Todd in his 1915 text ‘Byways of the Scottish Borders: A Pedestrian Pilgrimage’, Patrick was “whipped through Jedburgh, stood for half-an-hour at the cross with his ear nailed to a post, had both ears cut off, and was finally transported to the American plantations.”

It is said that Jean Gordon was drowned by a local mob in Carlisle’s River Eden in 1746 for expressing her strong Jacobite views.

King William I (c1700-c1784)

By the mid-18th century, William Faa, known as Glee’d-neckit Will, was acknowledged as King. Married three times in his long life, at least sixteen of his reputed twenty-four children are recorded in Kirk Yetholm’s parish registers, a boon for genealogists as many gypsies shunned the church – or vice versa.

King William II (1755-1847)

Will Faa II succeeded his father and spent most of his life in the village, with a spell as a pub landlord. A keen footballer, he boasted he had never spent a night in jail. This was a claim his successors were unable to make.

By the time of Scotland’s first census in 1841, the 85 year old widower ‘William Fall’ was the only Faa in the village, and after his death without heirs, on 9 October 1847 aged 92, the crown passed to his brother-in-law.

King Charles I (c1775-1861)

Charles Blyth came from a Yorkshire family that had settled in Kirk Yetholm. In 1796 he had married Will’s youngest sister, Esther Fall, born in 1774. At the end of October 1847, when he was crowned amongst scenes of ‘boisterous mirth’, Charles was a widower in his early seventies.

Although widely respected, Charles was jailed and then banished from Roxburgh for three years for housebreaking and assault in the 1820s.

Charles lived just long enough to be recorded in the 1861 census. It places him in the ‘Royal Cottage’ with his unmarried daughter Ellen (c1814-1893). Charles died that year on 19 August aged 86.

Queen Esther I (c1801-1883)

After the death of Charles I, his eldest son David Blyth (1796-1883) waived his rights, a decision he later regretted. Instead, he nominated his younger sister Ellen, nicknamed ‘Nell Blackbeard’. Although Ellen occupied the palace containing her father’s dark oak throne, she was successfully challenged by her elder sister Esther Faa Rutherford (c1801-1883) who had rushed back to Kirk Yetholm from her Coldstream home.

In the 1820s Esther had been banished with her father, and husband John Rutherford, known as ‘Jethart Jock’.

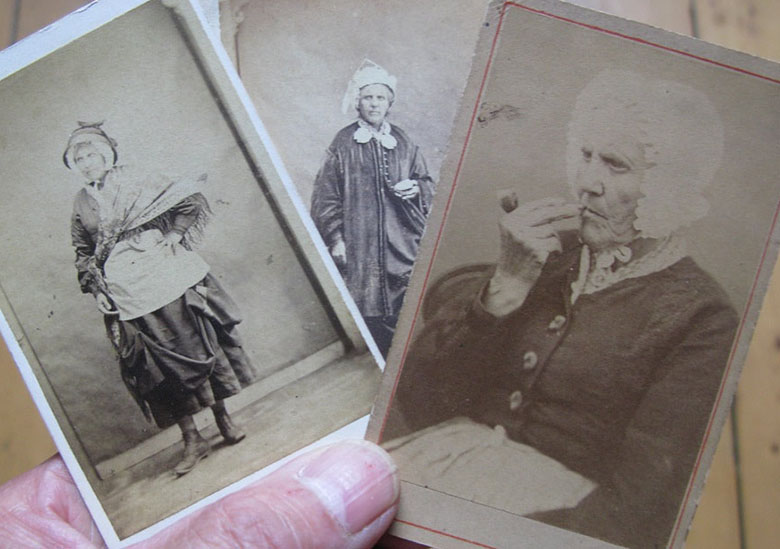

Queen Esther © courtesy of the Yetholm History Society.

Esther and Jock had many scrapes with the law. For Jock, the final straw was a guilty verdict for housebreaking and theft in 1847. Sentenced to 7 years transportation, he died on a Thames prison hulk the following year.

Meanwhile, Esther was in trouble herself. In September 1847 she was jailed for four months for assaulting her neighbour in Kirk Yetholm ‘with a rolling pin upon the head and back, kicking her along the passage and striking her on the face with her fists’, causing ‘an effusion of blood and injury’. Such unregal behaviour was glossed over in later, kinder, descriptions of Esther.

Like her father, the widowed Queen spent much of her later life in poverty. In the early 1880s she left the palace to lodge with her daughter in Kelso. After her death on 12 July 1883, there was a well-attended funeral back in the village.

The Interregnum (1883-1898)

From 1883 to 1898 there was no Monarch in the Palace, an interregnum if you like. Despite goodwill towards their Royalty there was still a great deal of anger and animosity to the Gypsies’ unconventional way of life.

The Trespass (Scotland) Act of 1865 had made it illegal for a person to camp on private property without the prior consent and permission of the owner. This effectively outlawed Gypsy Traveller culture. Later, the 1895 Scottish Traveller Report made offensive and shocking recommendations in its aim to combat nomadism in Scotland. This included suggestions of ‘extirpation’ (extermination) and deportation to the colonies. Such attitudes still linger and have had long lasting impacts on traveller communities.

By the end of the century the Faas were long gone, and many of the old Gypsy families had either left or intermarried with the local population, other travellers or recent Irish immigrants. Only around three dozen Gypsies still remained in Kirk Yetholm. Those who remained were fast becoming a curiosity rather than a threat. With an eye on benefits to the tourist trade, there was a flurry of interest in finding a new Gypsy monarch.

The Last King, Charles II (c1827-1902)

One of Esther’s younger sons, the ‘seldom sober’ Robert, was judged unsuitable to become the next King of the Gypsies. But happily, Charles Rutherford, Esther’s eldest son had recently returned to the village to run a poor boarding house with his wife Margaret Stewart. Despite being around 70 he was persuaded to become King.

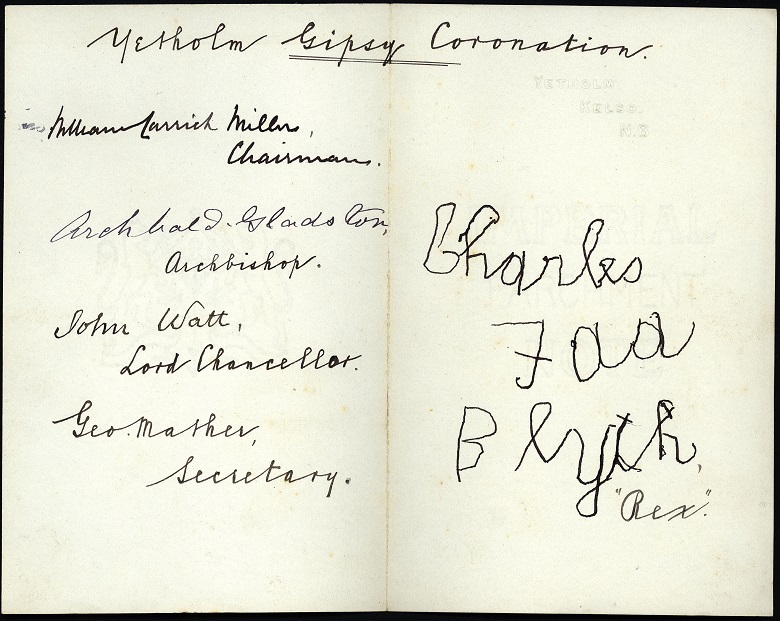

On 30 May 1898, despite a last-minute protest on behalf of the aforementioned David Blyth’s son, he was crowned. A shiny new brass crown was made for the occasion, replacing the old tin crown of his mother and grandfather. In line with tradition, Charles II was crowned by the town’s blacksmith. For the purpose of the ceremony the blacksmiths were jokingly referred to as the Archbishop of Yetholm, parodying the Archbishop of Canterbury’s role in the coronations of the monarchy of the United Kingdom. He signed his name, with difficulty, as Charles Faa Blyth.

© Scottish Life Archive. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

The widely reported coronation had a festival atmosphere with speeches, pageantry and a host of elaborate hired costumes. It ticked all the boxes as a tourist attraction, bringing thousands of local dignitaries and well-wishers to the village, if few Gypsies.

Coronation Day on Whit Monday at Yetholm, Roxburghshire, 1898 © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Charles moved into the refurbished Palace with its new brick porch. He died there, in his chair, on 21 April 1902 at the age of 77. His death certificate names him as Charles Faa Blyth Rutherford and his profession as ‘Gypsy King’. His soon forgotten widow died over a decade later in Kelso Union Poorhouse.

Charles Faa Blythe © courtesy of the Yetholm History Society.

The Gypsy Palaces

Ellen and Ester’s dispute over the royal succession after the death of their father, Charles I, led to a ‘rival’ palace being established in the village in the 1860s.

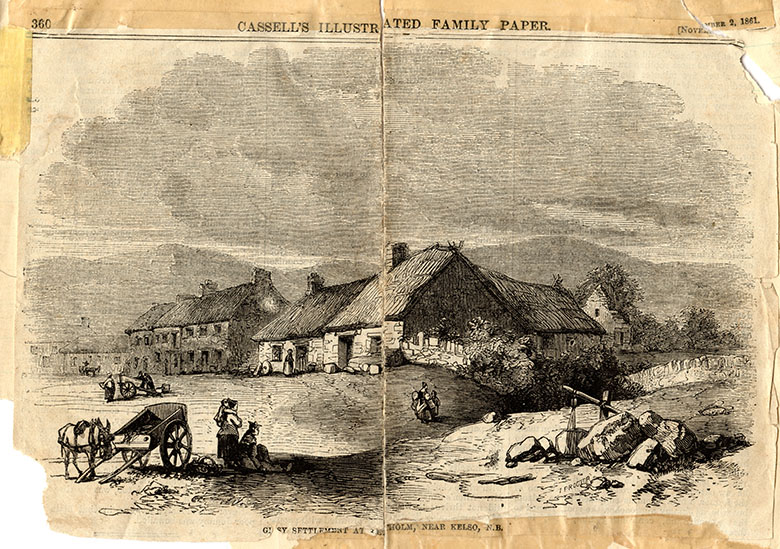

The original Gypsy palace, by artist John Proctor, who married a woman from Yetholm in July 1861. © courtesy of the Yetholm History Society.

The original palace was a one-storey whitewashed cottage on the east side of the triangular village green. Alongside many village houses it had a thatched roof, clay floor and open hearth. Ellen lived here until the 1880s, but soon after the roof collapsed. Today, Burnsyde House, which was built in 1895, occupies the site of the original Gypsy Palace.

Burnsyde House © HES (Buildings of the Scottish Countryside Collection).

The New Palace

Ellen refused to vacate the Old Palace, so Queen Esther moved into a house across the road on Tinklers Row. This house still survives today, although much-changed. The name of the road (now considered an offensive term) has long since been changed.

The new Gypsy Palace © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

In the 1860s it was a one-roomed dwelling, perhaps a thatched outbuilding behind the row, shown on the first OS Map of 1858. Over time it was modernised with a pantile, then slate roof, receiving a crowstepped brick porch in 1898. In more recent times an additional attic storey has been added.

Over time many curious visitors and well-wishers visited the two palaces. Charles I was visited by Sir Walter Scott and Esther was called upon by the Romany expert George Borrow.

The End of an Era

Despite renewed interest and a search for suitable candidates amongst the Rutherford clan in the 1930s, Charles II remains Kirk Yetholm’s last crowned Gypsy Monarch.

Banner image credit: composite image © courtesy of the Yetholm History Society.

More about Scotland’s Gypsy Heritage

If you enjoyed reading this blog, you might like to catch up with our other content exploring Scotland’s Gypsy Heritage:

- Rhona Ramsay and Maggie McPhee blog on the life of Jamie Macpherson in The loss of a son: Jamie Macpherson and his Gypsy heritage.

- Discover more about Scotland’s Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History in this video with Nawken (Scottish Traveller) Davie Donaldson.

- Watch to find out how Scottish Traveller, Jess Smith, preserved the legacy of the Tinkers’ Heart and ensured it was recorded as part of Scotland’s historic environment.