⚠️Content warning: This post contains descriptions of violence against women⚠️

On the night of 22 January 1732, a group of men broke into the bedroom of a home on Niddry’s Wynd off the Royal Mile where Lady Grange was sleeping. After a violent struggle, they blindfolded her and smuggled her out of Edinburgh.

This was the start of a long journey to and through the Hebrides. Lady Grange was never to be seen in Edinburgh again.

The events that led to the mysterious kidnapping of Lady Grange are steeped in conspiracy, deception and a marriage that had gone very, very sour…

Murderous beginnings

Rachel Chiesley, who went on to become Lady Grange, was one of 10 children from a loveless marriage between John Chiesley and Margaret Nicholson that ended in cold-blooded murder.

When the couple divorced, Margaret took her ex-husband to court to fight for financial support for her and her family. The judge, the Lord President Sir George Lockhart of Carnwath, ruled in favour of Margaret which enraged John Chiesley. He vowed to take revenge.

On Easter Sunday in 1689, Chiesley secretly followed the Lord President from a church service at St Giles Cathedral. In the middle of the High Street, Rachel’s father pulled his pistol and shot the Lord President in the back. Chiesley was captured immediately and taken to the Tolbooth. He made no attempts to hide his crime. The next day, Chiesley was taken to the Mercat Cross where he was hung, with the murder weapon around his neck. Rachel would have been around 10 years old when her father was executed for murder.

Original pencil sketch by James Skene of the ‘Heart of Midlothian’, St Giles and parts of the High Street. This is where most of these tragic events happened. © Edinburgh University Library. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

“Shotgun” wedding

The story of her father’s crime is an ominous foreshadowing of tales around Rachel’s own marriage.

When Rachel became pregnant out of wedlock, she allegedly held the father, James Erskine, at gunpoint and forced James to decide between death or doing the honourable thing and marrying her. She reminded him to think carefully given what her father had been capable of…

Portrait of Lady Grange. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Surprisingly, their marriage was pretty uneventful for the first few years after that and the couple had nine children together. They spent their time at their townhouse on Niddry’s Wynd off the Royal Mile in Edinburgh or at their estate at Preston in East Lothian which Rachel oversaw.

James Erskine was an advocate, judge and a politician. Although his brother, John Erskine, the 23rd and 6th Earl of Mar, was a key figure in the Jacobite rising, James had no part in it and he had become quite successful under the Union government. He became Lord Justice Clerk of the Court of Session and took on the title Lord Grange in 1710. Despite that, James likely had some connections to Jacobite circles.

Portrait of the young James Erskine © Earl of Mar and Kellie. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

A “stormy and outrageous” woman

A few years into Rachel and James’ marriage, the cracks started to show. Lady Grange was known for her outspokenness. She was said to have a ferocious, unpredictable temper and an indulgence in alcohol which led to rumours about her mental state.

Some accounts suggest Lady Grange may have indeed suffered from mental illness, that might have impacted her father already. Others attribute her reputation to societal expectations and her refusal to conform to societal standards.

Their marital trouble peaked when Lady Grange discovered that her husband had an affair with a woman named Fanny Lindsay, who owned a coffeehouse in Haymarket. It unleashed a wave of rage and paranoia in Rachel.

View of High Street, Edinburgh including John’s Coffee House on the right similar to the one Fanny Lindsay owned. There were many coffee houses in the nooks and crannies of Edinburgh’s streets. © Edinburgh City Libraries. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Rachel was so furious about the betrayal that she is said to have threatened to walk naked through the streets of Edinburgh. According to James, Rachel even slept with a razor under her pillow to intimidate him, reminding him once again whose daughter she was.

Rachel’s Revenge

They finally separated in June 1730. However, according to James’ letters, Rachel continued to harass James in the street and stood outside of his window shouting obscenities. Allegedly, James and the children had to hide in a pub for several hours on more than one occasion to escape Rachel’s wrath.

As James’ wife and the supervisor of their estate in Preston, Rachel was privy to her husband’s frequent meetings with Jacobite sympathisers in their home. Following his infidelity and their separation, she had no reason to protect her husband’s reputation anymore. In an attempt to get revenge on her husband perhaps, she started spreading rumours about her husband’s alleged allegiance to the Jacobite cause. She even took one of his letters to the authorities as proof of his alleged treacherous intentions.

In January 1732, Rachel booked a stagecoach to London. James and his friends became very uneasy about this move and feared she would raise suspicions about these serious allegations with the government. They decided it was time to put a stop to this.

Kidnapped!

On the fateful night of Rachel’s abduction in January 1732, she lodged in the house next to her husband’s. Several men stormed into the bedroom and kidnapped her after a violent struggle. The owner of the house, Margaret McLean, was seemingly in on the plan.

Lady Grange recounted the events in a letter she sent from captivity on St Kilda on 20 January 1738:

“Upon the 22d of Jan 1732, I lodged in Margaret M’Lean house and a little before twelve at night Mrs M’Lean being on the plot opened the door and there rush’d in to my room some servants of Lovats and his Couson Roderick Macleod he is a writer to the Signet

they threw me down upon the floor in a Barbarous manner I cri’d murther murther then they stopp’d my mouth I puled out the cloth and told Rod: Macleod I knew him their hard rude hands bleed and abassed my face all below my eyes

they dung out some of my teeth and toere the cloth of my head and toere out some of my hair I wrestled and defend’d -my self with my hands then Rod: order’d to tye down my hands and cover my face most pity- fully there was no skin left on my face with a cloath and stopp’d my mouth again they had wrestl’d so long with me that it was al that I could breath,

then they carry’d me down stairs as a corps.”

James covered up Rachel’s disappearance and it was rumoured that she had gone mad.

In her letter, Rachel suggests that the elaborate but risky plan of kidnapping her and taking her far away from Edinburgh to the West Highlands was plotted by Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat and Highland clan chieftains who helped smuggle Rachel out of Edinburgh. Lord Lovat was among the defeated at the Battle of Culloden and later convicted of high treason.

The plan of course also relied on James Erskine’s involvement. He was likely all too relieved to see the back of his wife. Of course, Lord Lovat denied all allegations and noted that suspicions raised against his friend James Erskine kidnapping his own wife were equally as ludicrous.

Long journey ahead

Allegedly, Rachel’s captors smuggled her out of the house to St Andrew’s Square in a sedan chair.

A sedan chair was an enclosed chair for one person, carried on poles by two men. This example was used in Edinburgh by Alexander Hamilton (1739-1802) and his son James (d.1839). © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

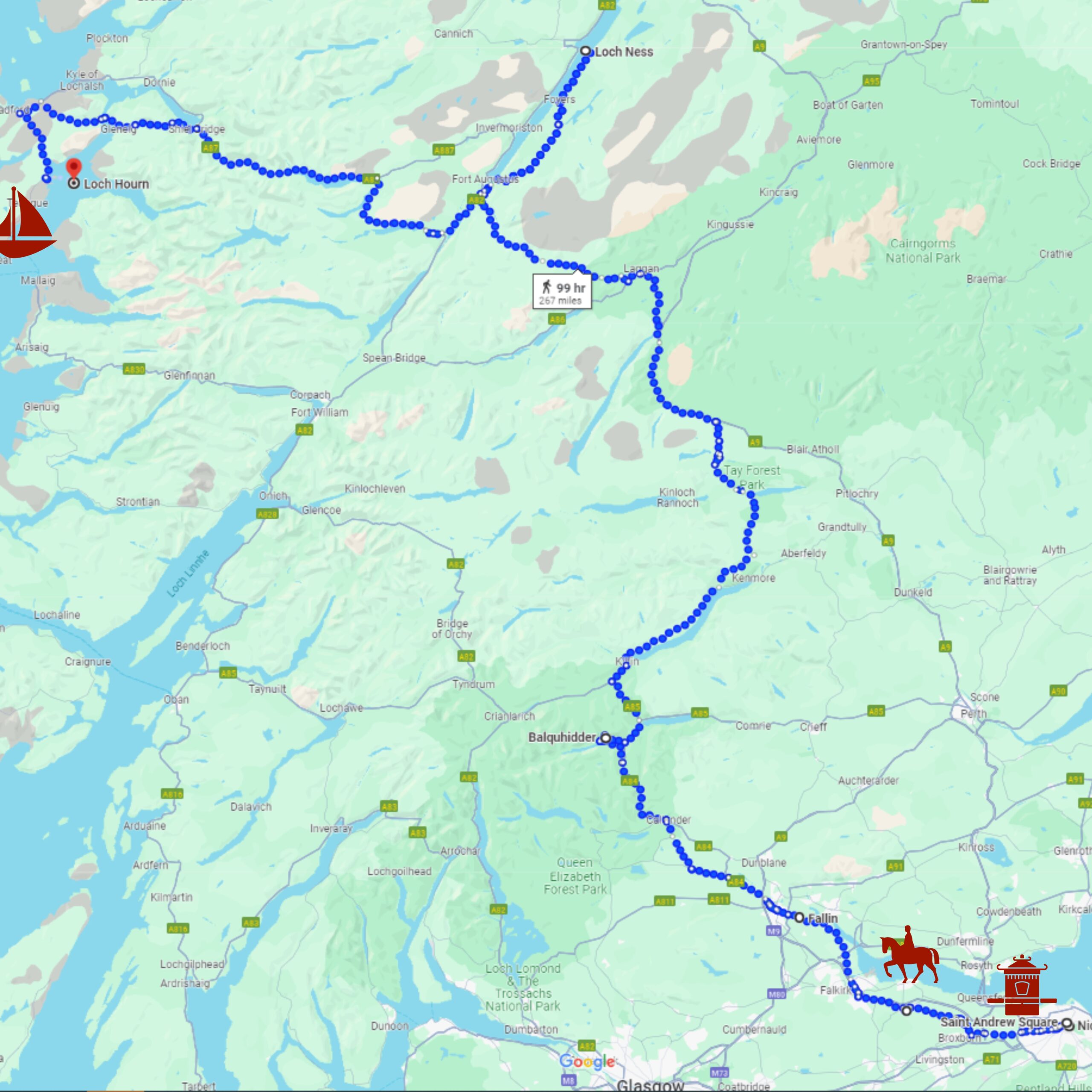

From Edinburgh, the party began their long journey on horseback to Wester Pomeis (now Fallin in Stirling) where they locked Rachel in a room of a house overnight with all the windows nailed shut. The party then rode to Balquhidder in Perthshire.

At Balquhidder, she was entertained with a meal and offered a freshly made bed. She tried to appeal to the people in the house and secretly pass on a message about her imprisonment but to no avail. St Fillian’s Pool was nearby, which people were bathed in aiming to cure insanity. It likely helped as a cover story for Rachel’s presence at the house and her pleas for help.

This is the route the party might have undertaken to arrive in the Outer Hebrides

They continued their long and arduous journey across land and sea to eventually arrive at the Monach Isles in the Outer Hebrides. All the while Lady Grange was sick with grief and despair, not even knowing which island she was on. Rachel mentions how isolated she felt during the two years, but it was nothing compared to St Kilda where she was moved to in 1734.

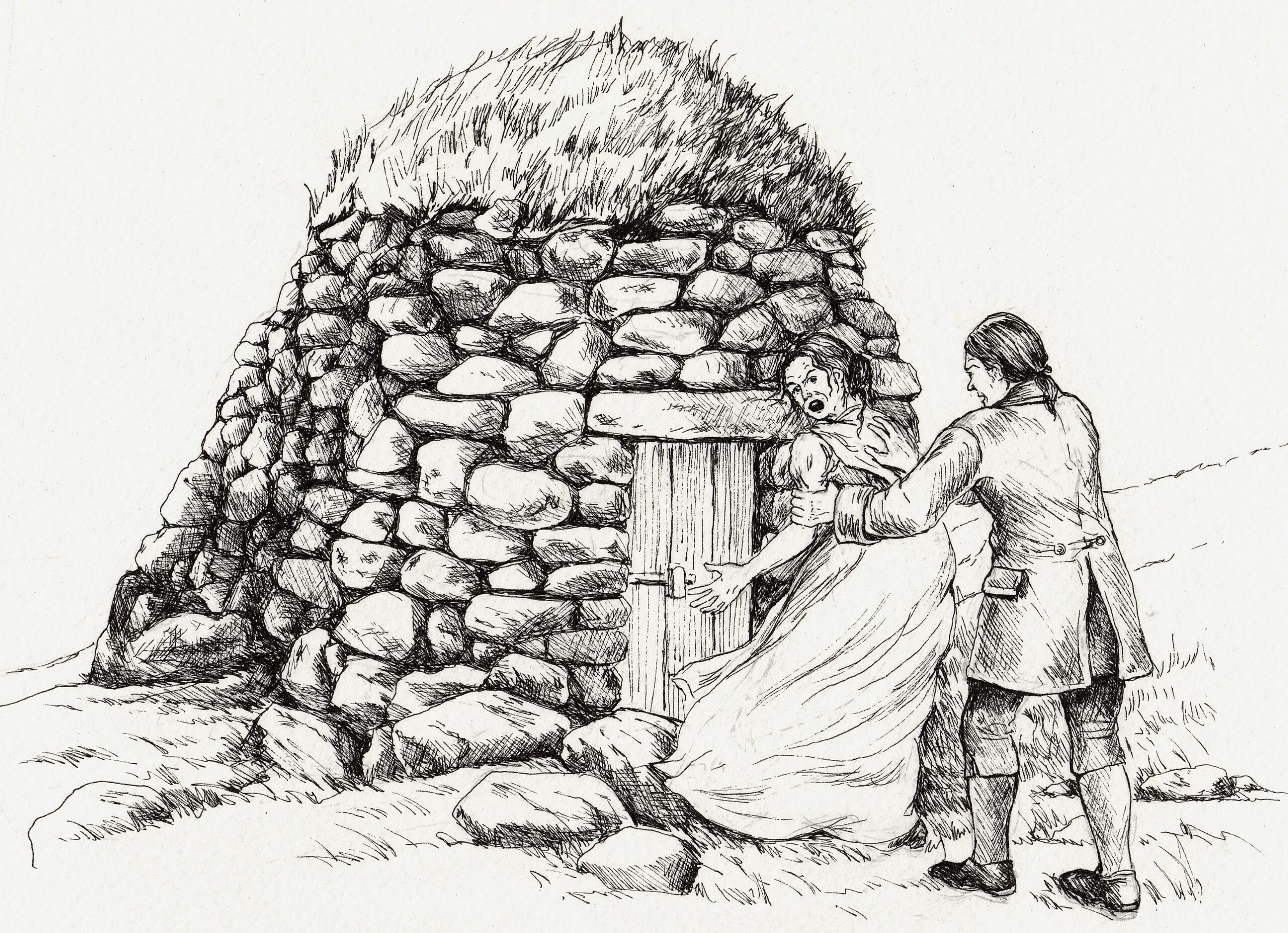

Lady Grange lived in a small house which has since been destroyed. In the 19th-century, a cleit was built on top of the space. The cleit collapsed in early 2022. This illustration shows Lady Grange taken to Hirta but the illustration shows the cleit, not the original house. © Dianne Sutherland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

A miraculous rescue for Lady Grange?

On Hirta, St Kilda, Rachel lived in a small house. Unable to communicate with the residents who spoke Gaelic, she kept throwing messages wrapped around cork floats into the sea, telling her story, hoping for rescue.

In a turn of fate, one of her letters finally reached her solicitor, Thomas Hope back in Edinburgh. The letter was left at his house anonymously. Thomas had known that Rachel had been taken from Edinburgh. But he had been assured that she was taken care of. Presumably he assumed she was in an institution to treat her mental illness. This was the first he’d heard from her in almost 10 years!

Rachel’s letter caused a furore back in Edinburgh and Thomas vowed to rescue her:

“I doubt not but she may be dead by this time, but if she is alive, the hardest heart on earth would bleed to hear of her sufferings ; and I think I can’t in duty stand this call, but must follow out a course so as to restore her to a seeming liberty and a comfortable life”.

In February 1741, Hope hired a boat to St Kilda and a group of armed men to launch a rescue attempt. He set sail and raced to St Kilda but the party reached the island too late. Once again, her captors moved Rachel – this time to Skye. It’s likely her husband and captors had caught wind of the rescue attempt.

One wedding and three funerals

Rachel reached Skye when she was 61 years old and lived there until her death aged 66 in 1745. She was buried at Trumpan churchyard. Another funeral was held at Duirinish where a crowd is said to have gathered to watch a coffin filled with turf and stones to be buried.

Some accounts mention that James Erskine held a funeral in Edinburgh, shortly after Rachel’s abduction. This may have helped cover up the crime. James went on to marry coffeehouse owner Fanny Lindsay.

No one but Thomas Hope ever searched for Lady Grange. None of her children launched inquiries into her disappearance. This might come as less of a surprise given the strained relationship she likely had with her children.

Whether Rachel did know too much and became a political prisoner or whether her paranoid allegations became a bit too dangerous for her own good, Rachel notes in one of her letters that:

“I’m not guilty of eny crime except that of loveing my husband to much, he knowes very well that he was my idol and now God his made him a rode to scourgeth me. […] it is impossible for me to write or for you to imagine all the miserie and sorrow and hungre and cold and hardships of all kindes that I have suffer’d since I was stolen.”

In for more women’s history in Scotland?

From A Scottish Adventure with Anne Lister, the real Gentleman Jack, to Dorothea Thomas, who came to Scotland from Grenada and changed Scots law – there is more women’s history to explore on our blog.

Sign up to our blog newsletter to get the latest stories straight to your inbox.